One of the questions that has come up in 18th & early 19th century costuming is what to call the ubiquitous scarves/neck-fillers. Are they handkerchiefs? Fichus? Neckerchiefs? And when did each term arise?

A Robe a la Anglaise worn Polonaised with a neckerchief, England, circa 1770-1780, LACMA

A handkerchief was a large square of fabric folded into a triangle, or cut and sewn as a triangle, worn around the neck throughout the 18th century.

If you were upper class, your handkerchief would probably be white. Poorer woman were more likely to wear darker handkerchiefs that would show less dirt. George Eliot describes Adam Bedes mother at the end of the 18th century with “her broad chest covered with a buff handkerchief.” Handkerchiefs were not limited to women – men wore then as bohemian alternatives to cravats and stocks.

They could be of linen or silk, or later cotton. For men and women, silk versions were the dressiest. They were frequently embroidered, and could be bought pre-made, but even the very wealthy frequently made their own, as the decorative finishes were considered appropriate needlework for a gentlewoman.

Marquise de Grecourt, nee de la Fresnaye by Jean-Laurent Mosnier, ca. 1790

Neckerchiefs were larger, fuller handkerchiefs – both garments were neck wear unless the term ‘pocket-handkerchief’ was specifically used.

Mme Mole Reymond by Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun, 1787

A buffon (or buffont) is a large, sheer neckerchief worn to cover the bust and fill in the neck in the 1780s and 90s. They were often starched to further exaggerate their fullness, and to assist in creating the desired pigeon breast effect, and very occasionally wired into position. A German lady visiting London in 1786 described “Ladies with neckerchiefs puffed up so high their noses were scarcely visible.” In France the buffon was called a fichu menteur.

Costume Sketch featuring a lady in what the English would call a buffon, Anonymous, French, 18th century, Possibly connected to Antoine Caire-Morand (French, Brian̤on 1747 Р1825 Turin),1785-1790, MFA Boston

Fichu was, broadly speaking, the French term for a neckerchief or scarf. The term appears in French from at least as early as the mid-18th century, and was adopted for English use as a more elegant alternative to neckerchief in the early 19th century.

“Jolie Femme en contemplative” wearing a large fichu, from the Gallerie des Modes, 1784

It’s clear in French fashion plates that fichu had a broader definition than the English neckerchief, and was used for any type of scarf or wrap, such as this fur trimmed number:

Fichu de Velours, Redingote de Merinos, Costume Parisiene, 1813

18th century French fashion plates show a whole range of fichu, from shawl-like fichu, to fichu worn as turbans.

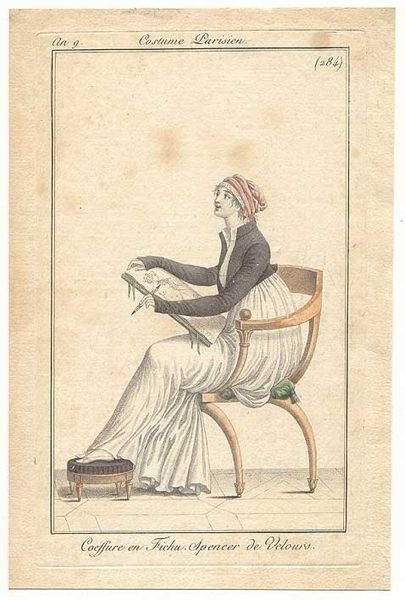

Coiffure en Fichu. Spencer de Velours Costume Parisiene 284, circa 1800

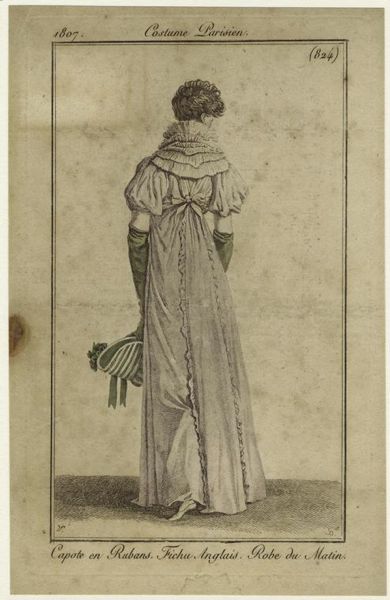

Different styles of fichu were given different names some prosaic, some fanciful. There was the extremely ruffled multi-layer fichu anglaise:

Capote en rubans, fichu anglais, robe du matin

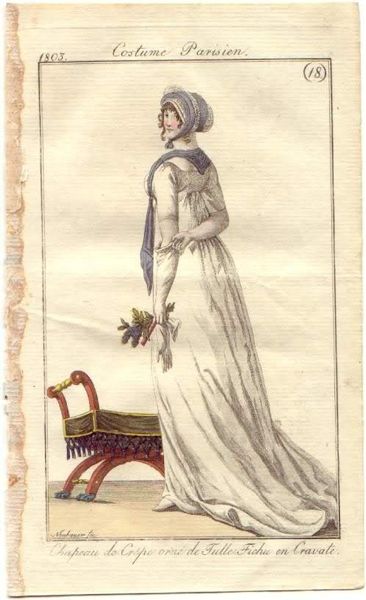

And the front tying fichu cravat:

Fichu Cravate, Costume Parisiene 1806

To the uplifting fichu ceinture (literally ‘belted fichu’)

Peigne d’Or, Fichu-Ceinture, Costume Parisiene 151

Because the French use of fichu encompassed a broader spectrum of scarves than the narrower English terms of handkerchiefs and neckerchiefs its more common to see them in colours. When Charlotte Corday stood trial for murdering Marat in July 1793 she wore a rose pink fichu with her spotted muslin dress and black hat with green ribbons. Fashion plates in the late 18th and early 19th century show a whole range of colours, from fichu that matched hats, to wildly patterned fichu scarves.

Day dress worn with crepe hat and fichu worn in the cravat style, Costume Parisiene 18, 1803

Chapeau de Velours. Fichu quadrille, Costume Parisiene 262, ca. 1800

Fichus could also be worn about the head as turbans as well as around the neck. 1797 saw a fad in France for fichus a la marat, after the turban worn by the revolutionary in David’s famous painting of his death.

Jacques-Louis David (1748—1825), The Death of Marat, 1793, via Wikimedia Commons

This 1788 fashion plate shows a fichu tied over a bonnet (though I haven’t figured out if it was meant to be the colour of a marmot, or somehow the style evoked a ground squirrel).

Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français. Jeune Dame coiffee d’un Bonnet rond avec un fichu en marmotte, un Ruban en rosette, une Polonoise et un mantelet blanc, 1788

Once adopted into English, fichu became the go-to word for most female neckwear throughout the 19th century. It lost the broader sense of scarf and wrap that had characterised its usage in late 18th and early 19th century French fashions, but expanded in shape and aesthetic from the basic squares and triangles of 18th century neckerchiefs.

A Fichu Cape Wrap.

Undersleeves and fichu. 1863

Different styles of 19th century fichus were often called by 17th and 18th century inspired names. The 1850s saw a revival of a common 18th century style, with a fichu draped round the neck, crossed over the bodice, and tied around the waist in front or back (as in the portrait of Madame Mole near the top of this post), which they called the Marie Antoinette fichu. A decade later a similar style but with the addition of a ribbon was called the Charlotte Corday fichu. A ruffled 1890s version was called the Martha Washington fichu.

The Ladies’ Home Magazine 1860 – Fichu

Lady with sheer fichu and striped wide-necked dress, c. mid-19th C. via pinterest

After falling out of fashion in the 1870s, the fichu saw a revival at the end of the 19th century, when the extremely feminine, frilled fashions made lavish use of lace wraps.

Fichus lost ground in the 1920s when fashions changed to simpler, sleeker styles that revealed more of the female body, though they still appeared as pared-back wrap necklines.

The last examples of fichu in common usage in fashion is to describe collars in the style of fichu.

… a double fichu collar of white taffeta trimming the decolletage. Auckland Star, 21 June 1933

These frocks often specifically referenced the 18th century in decoration, and sometimes name. Our old friend Charlotte Corday returned to give her name to this dress with a wide wrapped and tied collar that evoked historical styles.

So, to sum it up:

If it’s 18th century, and the outfit is English, you can call it a handkerchief or neckerchief, unless it is the the extreme 1780s/90s style, in which case it is a buffon. If the outfit is French, pretty much any scarf, shawl, wrap or neckerchief can be a fichu. After 1800 fichu is the most commonly used term, though handkerchief and neckerchief are still used by the lower classes/less fashionable. There were also different kinds of fichu, from the fichu-pereline, to the fichu cape wrap, to fichu-robings.

Sources:

Buck, Anne. Dress in 18th Century England. B. T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1979 (pgs, 96, 138, 150-1, 155, 182, 200)

Cummings, Valerie. The Visual History of Costume Accessories. B. T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1998 (pg 64)

Cunnington, Phillis. Costume in Pictures. Herbert Press Limited: London. 1981 (pg. 81, 92)

Ribeiro, Aileen. Fashion in the French Revolution. B. T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1988 (pg 58, 134)

Thank you so much for this post! You have no idea how timely it is. We were just discussing this issue of what-to-call-the-white-thing-around-the-neck while cataloguing some portrait miniatures a few weeks ago. Any thoughts on how the term “pelerine” fits in with all of this? I’ve always heard that pelerines matched a particular outfit, like pelerines in the 1830s made out of the same fabric as the dress…any thoughts?

Love these terminology posts!!!

flickr.commetmuseum.orgmetmuseum.orgYou’re welcome! I’m glad it was helpful.

I’m going to do a full post on pelerines, but basically a pelerines is usually more shaped and extended collar / cape-like than a fichu. Pelerines were also usually made of more substantial fabric than fichu – like matching dress fabrics (though they didn’t have to match the dress), rather than fine linens and lace. Fichu in the shape of pelerines (like this one, misidentified as a lace shawl) were called fichu-pelerines.

Here is another one that was probably called a fichu-pelerine.

And a fascinating example made from feathers.

The lines between the two do seem quite blurry though, and I suspect they were at the time as well.

I did enjoy that! Thank you kindly. Here I sit, wearing my lacy woollen shawl, thinking that actually it is a bit small for a shawl and is more like a fichu! Adds class to the ensemble of flannellette nightie, down bed boots – and woollen lace fichu!

That was a marvelous post!

I guess this means I made a handkerchief for the last challenge, not a cravat.

This fichu terminology thing has always confused me. I’m totally going to starch my giant 1780’s gauzy triangle, which doesn’t puff as much as it should. I’ll have to remember to call it a buffon.

I’ve been using the word fichu because I live in an area of Canada that was settled by both the English and French, and am half French, although I don’t speak it. I’m still not sure whether I should keep calling 18th century neck thingies fichus. Probably not.

I have always found that painting of Marquise de Grecourt sort of unsettling, her face looks so modern, I think it’s the eyebrows.

Thank you for writing this, it must have taken a really long time to research.

Regarding the “fichu en marmotte” in the polonaise plate – I translated it as “sleepyhead kerchief“, as it’s apparently a figurative alternate meaning (why?) and seemed to fit with the style.

Lovely post! I didn’t know buffon/bouffant was adopted into English so early.

How interesting about the “fichu en marmotte”. I can make a guess at the reason for the name ‘sleepyhead kerchief’ – without being able to prove it, of course. Marmots hibernate. Curl up in their burrows for the winter in the Alps. The young lady in the fashion-plate has one of those high bouffant hairstyles that would have been left untouched for a while, and I imagine that people wrapped them somehow at night to stop messing them up when they slept. Some sort of cap arrangement, rather like the one she is wearing, held on with a kerchief would seem quite likely.

Where we English speakers use ‘dormouse’ as our symbolic sleepyhead (thanks to ‘Alice in Wonderland’ I imagine), it is quite likely that the French, especially those near the Alps, would use ‘marmot’.

Sounds plausible?

interesting. I am learning so much from your site Leimomi that it makes up for me not being able to study at a university.

Ooh, after this post, the mention of reworking a muslin dress into a handkerchief in Northanger Abbey suddenly makes more sense!

Mr Tilney also mentions (quoting his sister, that is) making it into a cloak, though – I now wonder what that would have looked like!

Thanks very much for this fun and informative post. I’m working on my baroque dance costume, and wanted to be sure I had all my terminology correct.