For this terminology post, we’re looking at glove terms: fourchettes, quirks, tranks and points.

I love these words just because they are so random and specific. Other than glove makers and fashion historians, who would know that there are specific words for the different parts of gloves?

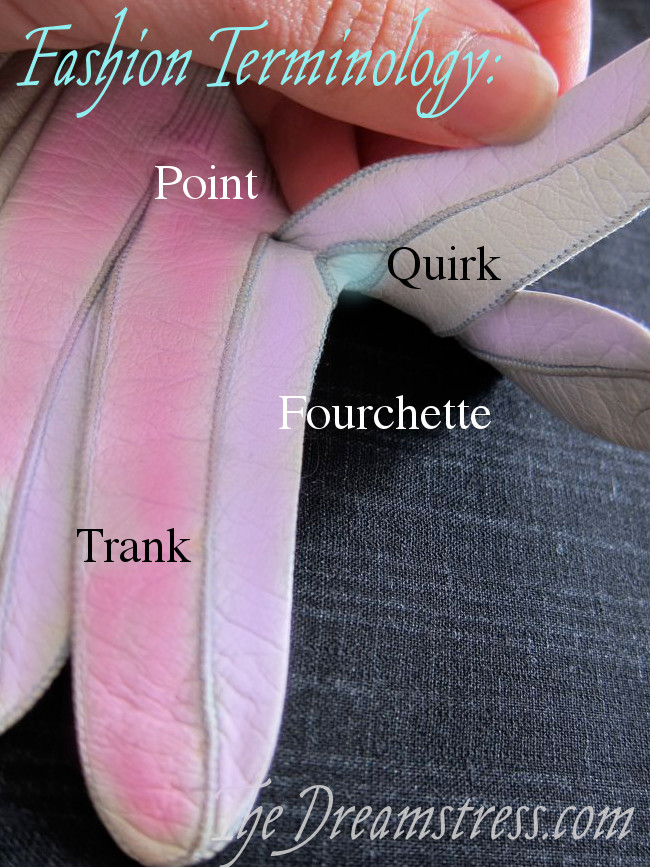

The main piece of a glove, with the back and front of the glove and the tops and bottoms of the fingers all cut in one, with only one side seam, is the trank. It’s shown in pretty pink in the photo above.

Going between the fingers, and attached to the trank, is the fourchette (in lovely lavender in the coloured photo above), also called the fork or forge which is:

A forked strip of material forming the sides of two adjacent fingers of a glove

In other words, this bit:

It is from the French, for forked, because a fourchette is forked, and allows the fingers to fork.

Some fourchettes have an extra little V gusset at the bottom, called a quirk (shown in beautiful blue in the coloured photo) or querk (scrabble players take note!) to allow more movement and better shape to the fingers.

A late 17th century description of the glove makers art describes quirks as:

Querks, the little square peeces at the bottom of the fingers

Gloves cut of very soft, stretchy leather did not always need a quirk, so their forchettes are a simpler strip, or have the quirk cut in one with the forchette:

When the glove thumb piece and its quirk are cut in one, it is a Bolton thumb glove.

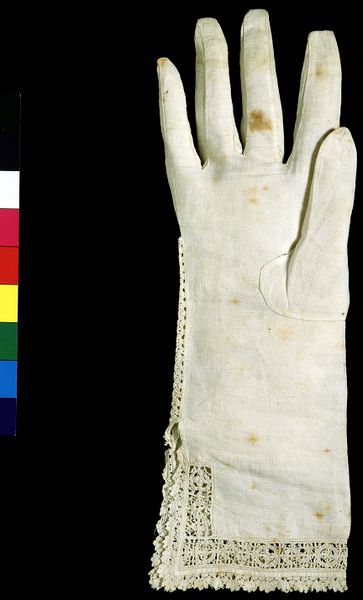

Knit gloves don’t usually have fourchettes, and some modern stretch fabric gloves also forgoe them, but most leather gloves from at least the 17th century to the present have some form of fourchette.

North and Tiramani’s Seventeenth Century Women’s Dress Patterns has two excellent pattern for early 17th century glove with fourchettes (though sadly, they just call them forks) and quirks.

Usually fourchettes just form the space between two fingers, but there is a type of glove called a continuous fourchette glove, where one strip of fabric starts at the pinkie and runs up the side of the pinkie across the tip, down the side, up the next one, and so on until the end.

This type of glove may date back to at least the 13th century BC (although the glove mentioned in that pamphlet does not shows up on a search of the Metropolitan Museum of Arts collection database).

And finally, if you have ever wondered about the seam lines across the back of gloves, they are called points and originated as extensions of the finger pieces on gloves, to aid in better shaping.

Now, how many times can you come up with an excuse to use these terms in a week? 😉

If you are interested in glove-making, I highly recommend Eunice Close’s ‘How to Make Gloves’, or the aforementioned pattern in Seventeenth Century Women’s Dress Patterns.

Sources:

Close, Eunice, How to Make Gloves, 1950

Johnston, Lucy. Nineteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 2005

North, Susan and Tiramani, Jenny. Seventeenth Century Women’s Dress Patterns. London: V&A Publishing, 2011

What wonderful gloves! And at the end, I recognize some of them! 🙂 Happiness.

“Querk” will be a valuable addition to my Scrabble vocabulary!

Lovely post – so interesting.

I love winter – then I can wear my gloves. Yes, as an adult I love wearing the gloves that were such a hated part of my school uniform. Nothing beats a beautifully made pair of kid gloves in a favourite colour. Wear more gloves, I say.

I love these terminology articles.

Gloves are so pretty. I’ve often wished we’d wear gloves again, sigh.

The Eunice Close booklet was fun to read. Homemaker’s crafting their own gloves and gloves for the family…whoa! Reminds me of the 19th (?) century book you costumers refer to written for homemaker’s on how to construct shoe’s for themselves and their families.

Making gloves is much more practical.

The US Army Quartermaster Research and Engineering conference on military gloves that you brought our attention to was mind blowing! They really RESEARCH creating gloves for specific military applications. Scientist’s from MIT and Johns Hopkins Medical Research Facility? Wow!

I get my gloves at WalMart. Meh!

L

Oh this is really cool, I have some lovely red and blue leather thats industrially glued to stretch fabric, perfect for gloves!

There is one little thing I’d like to point out, I think the pink and lavender would be very difficult to make a difference in for people who are color blind ^^’ I’m not colorblind myself so I can’t really tell you if it is but one of my friends is and the hardest colors to differentiate for her are pink and purple.

Nice post! I knew what fourchettes were, and I think I was familiar with points as well. The other terms, not so much.

I love gloves and have been buying vintage ones (mostly 1950’s) whenever I could find them cheaply. I love the look of those really slender gloves made from soft stretchy leather. All modern gloves look bulky and roughly made in comparison.

And modern gloves are usually stitched on the inside, like clothes while many vintage gloves are stitched in a different way…

I tried making gloves once, using a Vogue pattern which was supposed to be for jersey fabric (but included fourchettes). That was so much too big that I gave up. I’ve been meaning to try again using that vintage article…

Oh! Quirks/querks. I was extremely pleased to find late 18th/early 19th century gloves that had them, just like the modern gloves I have do. It’s nice to know just how old that feature is and what it is called! (Even if it’s just in English; I wonder what the Czech terminology is…)

Mmm, gloves….

So neato! Great post. Your blog and This Old House (where the carpenters are throwing around other obscure constructing terms) are so satisfyingly pleasing!

I love your terminology posts!

This makes me want to go out (or home rather) and make gloves!

… maybe after buying that book though

Thank you for the terminology! It’ll come in handy next time I’m cataloguing gloves.

Does anyone know of any glove maker in the United States who still sews in the quirk gussets ? I was told that the quirk gussets make for a better fit and a stronger glove ?

gentlemansgazette.comFort Belvedere. http://www.gentlemansgazette.com/shop/leather-goods/gloves

Not sure if they are made in US or elsewhere.

Thanks for this post. I am trying to find someone who can teach me to make leather gloves. There was to be a course in the US but it was cancelled. Do you have any info where I can go for hands on learning experience in the UK or US? Thanks.

What a lovely post! Both my mother and my grand-mother were gloveresses, so I was used from very early to watching one or other of them busily working on the gloves that they made at home, and quirks and fourgettes were very familiar words to me. The gloves were sent out from the factory of I & R Morley in Worcester for their out-door workers to make from the cut-out leather shapes. The backs and fronts were sent together with scraps of leather from which the fourgettes and quirks had to be cut. In most of the gloves that Mum made there was only one quirk which was inserted at the base of the thumb. The gloves had to be trimmed using scissors which needed to be very sharp, and another important piece of equipment was the gloving stick. These came in several sizes, made of wood and about twelve inches long with a bulge in the middle, tapered to a rounded end, each end being of a slightly different diameter. They were used to turn the the gloves in order to insert linings. As gloveresses were paid per dozen pairs of gloves, and only for those that passed the quality control at the factory, the work was hard and demanding. The pay was low, no allowances made for the electricity used, and certainly no attention paid to how many hours it would take to complete the number of dozen they were expected to do in a week. Mum was even expected to go to the factory to collect her pay every week. Worcester was famous for many years as a place where quality gloves were manufactured, and Queen Elizabeth the First was been a recipient of a pair of Worcester gloves as a gift from the City. There is also a Church spire near to the river Severn in Worcester which is called the Glovers’ Needle because of its shape, being pointed at the top with two empty spaces opposite one another at the bottom where the rest of the building has been knocked down, which resembles the hole in the top of a needle.