I made three new dresses for the Katherine Mansfield Garden Party at Hamilton Gardens, and was very happy with them all, but the one that makes me happiest is definitely this one:

This dress started with the parasol. I found the parasol for $6 (!) at a Dunedin op-shop during my visit. It is just gorgeous: beautifully made, real silk, hand embroidered. It’s definitely early-mid 20th century Chinese export-ware, and it’s the oldest and most beautiful parasol I’ve ever found at an op-shop.

Knowing that the Mansfield Garden Party was coming up, I immediately thought of making a dress to go with it. I first tried for fabrics in the aqua-blue, but they were too matchy-matchy, and wouldn’t show up well in the greens of a garden. My yellow stash yielded this palest yellow muslin gauze (which I’ve seen sold as mull in modern fabric stores in NZ, though it’s not the same as a technical or historical mull), and the wise Nina of SmashTheStash advised that when in doubt, I should always go with yellow. Clever woman!

I was quite happy with the finished dress, but slightly worried that it wouldn’t be able to hold its own against the other dresses I was showing: the 1905-07 greek key dress, and a new 1911-13 summer frock. Late Edwardian and early ‘teens are always so popular, and appeal to everyones inner princess. 1920s, on the other hand, are not at all so popular, and neither is pale yellow.

Luckily I needn’t have worried at all. Helen, my wonderful model, suited the dress perfectly, and really brought it to life. She looks gorgeous in the photos, but I wish you could see how she moved in it.

I heard rave reviews from party-goers all day, especially when she took a Charleston lesson, and turned the Charleston into a delicate, dainty, floaty dance, which perfectly suited the dress, and made it look like the sort of thing that might have been danced by the sheltered daughter of an upper class family in early ’20th century Wellington.

Helen is wearing the dress over a slightly make-do early ’20s silk slip, and Rosalie stockings in ivory merino, along with American Duchess Astoria shoes.

I’ll blog about the slip and hat shortly.

The dress itself is a basic T-shape based on the basic 1920s dress shape I developed for my Vionnet chiton dress, with gathered side panels cut as-one with the dress, and pintucks for shaping. I’ve ornamented it with a daisy-cluster of falling ribbons, inspired by instructions for ribbon flowers in 1920s magazines and decoration books.

The pintucks were an inspired design element (my original choice was insets of lace, but I wasn’t happy with my trial samples), as they help shape the dress by creating almost a princess seam effect, even though they are perfectly straight. They also help to lengthen the dress visually, emphasising the longer, more columnar look of early ’20s fashions.

They were also an absolute pain to sew. The muslin has very high sheer (wibblyness, like engineering sheer, not see-through-ness), and getting them to lie perfectly straight up and down the dress, and straight to each other, was definitely not the most fun thing I’ve ever done! Pintucks are always evil, but in the fabric they truly are the devil’s handiwork (as, in a perfect example of ‘great minds think alike’ Stephanie pointed out in a comment on my post on the Garden Party, after I’d already named this dress!).

Going back to the pattern for the dress, some of you may be thinking “hmmm…a basic T-shape with side gathers….sounds like a One Hour Dress.”

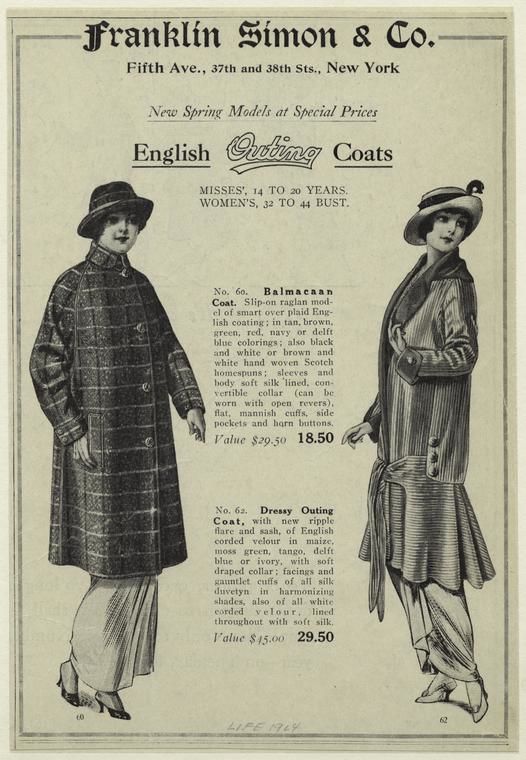

It is, but it isn’t. The one-hour-dress idea doesn’t appear under that name until at least 1923, but there are certainly images of dresses from 1920-1922 that are built around the same concept: a very simple T-shaped bodice, with an attached or cut-as-one skirt.

The One Hour Dress gets a bit of a bad rap: even the book description on Amazon calls it the ‘infamous “one hour dress,”‘ and as soon as I posted an image of this one a particularly tactless friend on the internet sniffed “Oh, yet another one hour dress.” However, if you break down 1920s dresses, they are basically all one-hour dresses. Very few official ‘One Hour Dresses’ actually take only an hour to make, and the basic shape is just the shape of 1920s dresses – particularly those from the first half of the decade.

Sure, they can be made slightly more elaborate with all-over embroidery, rows of ruffles, paniers to make them robe-de-styles (really, most robe de styles are sleeveless or have cut-on sleeves), handkerchief or gathered overskirts, but it is entirely possible to make huge amounts of early 1920s fashions as One-Hour dresses, and as soon as you allow set-in sleeves, well, you’ve got the basis for 95% of early ’20s looks.

The One Hour Dress is a fascinating concept, and there are dozens of different ways to make it, but sometimes I think it has become so well known that we don’t realise how ubiquitous that shape really was, how it’s a totally logical evolution from the kimono or Magyar bodices of the 1910s, and how often it was used by everyone from Vionnet to home dressmakers, even before Picken gave it an official name.

For more information on making a dress like this yourself, or anything in the One-Hour-Dress range, check out my article on the Vionnet-inspired Panel dress in Threads Magazine, Festive Attyre’s posts on One-Hour Dresses, and the One Hour Dress books (compiled from Mary Brooks Picken’s articles for the Women’s Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences).

What the item is: a summer of 1921 garden party dress. This wasn’t originally supposed to have tucks or pleating, but it just looked so boxy when I first made it, and the tucks helped to give it some shape, plus adding vertical interest.

The Challenge: #2 Tucks & Pleating

Fabric/Materials: 3m of palest yellow cotton mull (from an op, shop, >$1pm).

Pattern: Essentially the ‘1 hour dress pattern’ – though the idea wasn’t published under that name until 1923, earlier dresses from the late teens & 1921-22 show the same basic cut and essential construction.

Year: 1921

Notions: 8m of rayon petersham (.60pm), 1m silk ribbon ($1), cotton thread ($1).

How historically accurate is it? Pretty good as an example of a homemade dress from the era. My stitch length is a wee bit long, and I cheated and used an invisible hem stitch. 80%

Hours to complete: Definitley not 1 hour! More about 13

First worn: By a model at the Hamilton Gardens ‘Mansfield Garden Party’ on Waitangi weekend.

Total cost: >$10