Bizarre silks are silk fabrics (obviously) that were fashionable in Europe from the mid 1690s to the 1720s. They featured large, asymmetrical designs, vivid colours, fantastical floral designs which were Oriental in inspiration, and an emphasis on the diagonal ‘serpentine line’ which would later come to characterise the Rococo style. The first bizarre silks were woven in Lyons, France, but by the early 1700s they were also being made in Spitalfelds, England, and to a lesser extent in Italy.

The name ‘Bizarre Silks’ is not period – it wasn’t used until 1957 when art historian Dr. Vilhelm Sloman coined the term to describe the style. Dr Sloman believed that bizarre silks were made in India and imported into Europe, but subsequent scholarship has made it clear that they were exclusively produced in Europe.

According to my research, there is no particular set of term that was used in the late 17th & 18th centuries for the fabric design – they might be described as Oriental, but generally they were just the popular style, and no particular distinction was made between the large, florid, asymmetrical designs, and earlier more formal Baroque designs (another term that wasn’t used until in-period) and lighter, more naturalistic later Rococo silks (ditto as with Bizarre and Baroque). It’s only with the perspective of time that we’ve made a clear stylistic distinction between the design periods in silks, and have needed to come up with a comprehensive name to describe the group.

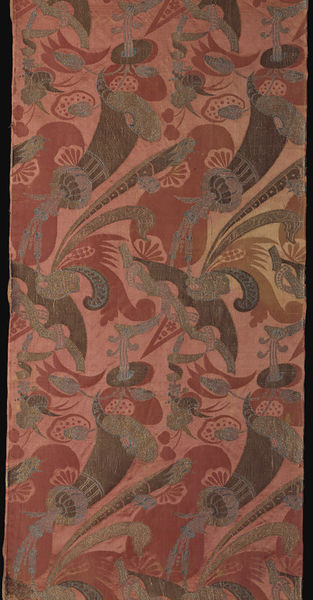

Here is a formal, symmetrical earlier Baroque silk:

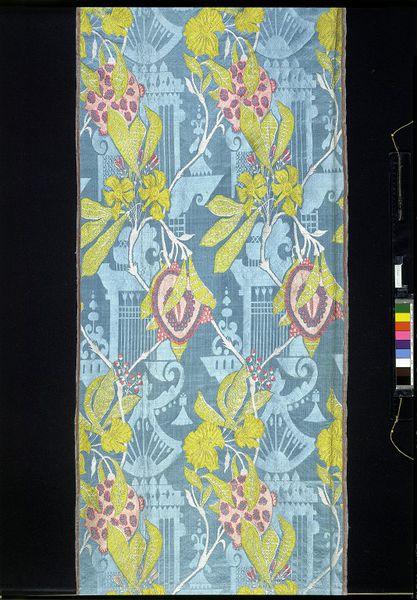

Compared to a wildly patterned, asymmetrical bizarre silk with clear Japanese influence:

The development of the patterns seen in bizarre silks was influenced by the rise of trade in Indian chintzes and Chinese silks, facilitated by the English & Dutch East India Companies, in the 17th century. The English and French fabric industries were hugely impacted by the flood of imported fabrics, and took measures to protect and promote their industries. Some of these measures were legal: France passed laws prohibiting the wearing of Indian chintzes in 1686, and England passed similar laws against the importation or wearing in 1701 and again in 1720. The other response was to cater to the new desire for exotic patterns by creating them at home and specifically tailoring them to the tastes of the local market: the result was bizarre silks.

Like actual Indian chintzes and painted Chinese silks, bizarre silks featured exotic plant-shapes, unusual mixes of vivid colours (printed Indian chintzes, unlike their Western counterparts, were colourfast and washable), and asymmetrical patterning.

Man’s bizarre silk sleeved waistcoat, France, c. 1715. Silk satin with supplementary weft patterning bound in twill (lampas). LACMA M.2007.211.40

Designers took some of their inspiration from actual experiences in India and the far East (the English East India company actually sent textile designers and weavers out to India from the 1660s onwards), from textiles that were sent back from India, China, and Japan (the first kimono to reach Europe were given as gifts to officers in the Dutch East India Company in the 1650s), from botanical books, and new plants reaching Europe (stylised pineapples, which were brought to Europe from South America in the 1660s are a common motif in bizarre silks), to which they added a huge dash of fantasy and imagination.

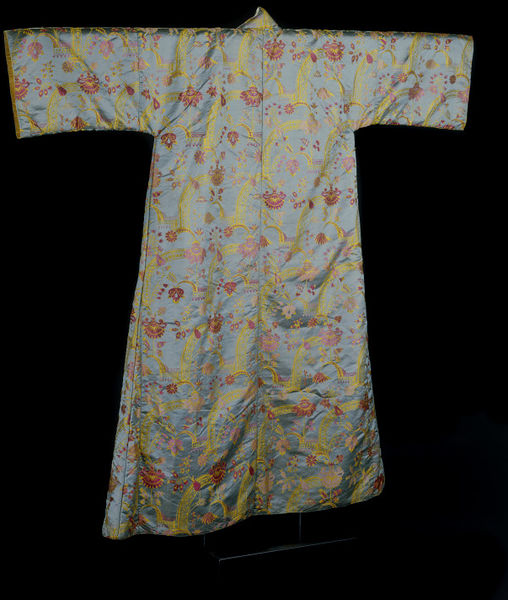

This unusual variant of bizarre silk features Oriental inspired scenes:

Dress, petticoat, and stomacher (dress) possibly Dutch, About 1735; dress restyled about 1770, France, MFA Boston

The large scale patterning of bizarre silks was complemented by changes in fashion around 1700, where the slimmer lines of 17th century mantua began to give way to fuller, more rounded styles which better displayed the large designs of bizarre silks.

Evidence suggests that bizarre silks, while expensive and luxurious, were more likely to be used for informal garments, such as banyan and informal mantua, while formal garments like robe de cour and English court mantua were more usually made from earlier styles, or the lace inspired and more naturalistic florals that would replace it.

This mantua in 1720s fabric showscases the fabrics large-scale design, which is transitioning from the full bizarre style, to the more delicate abstract lace-inspired designs of the 1730s onward.

While Bizarre silks were used for a full half a century, there were changes in the most popular styles and aesthetic across that timespan. You can see a good brief overview of the changes in this exhibition.

Fabric designers who made bizarre silk designs include English designer of Spitalfields silks, James Lehman (1688-1745), who is considered to be one of the first English designers of bizarre silk, Christopher Baudoin (1660, 1739), and Joseph Dandridge (1665-1746). French and Italian textile designers of the same period are not so well document.

Bizarre silks fell out of favour in the 1720s, giving way to more delicate motifs based on lace, and then large floral designs, and finally the small, naturalistic designs of the height of Rococo. Gowns of bizarre silk continued to be seen throughout the 18th century, as the fabric was so durable and valuable that older gowns were re-modelled to fit current trends.

The fabric of this gown was woven in the 1730s, and the gown was re-styled again in the 1760s. The fabric shows the clear move to more naturalistic florals, with the last vestiges of the bizarre style still evident.

Dress (robe a la anglaise) about 1735, restyled 1763, Silk; brocaded plain weave 1990.513a-b, MFA Boston

Sources:

Arnold, Janet. Patterns of Fashion: The Cut and Construction of Clothes for Men and Women c. 1560-1620. London: Macmillian. 1985

Brown, Clare. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century from the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: Thames and Hudson. 1996

Cumming, Valerie and Cunnington, C.W.; Cunnington, P.E, The dictionary of fashion history (Rev., updated ed.). Oxford: Berg. 2010

Ginsbert, Madeleine (ed). The Illustrated History of Textiles. New York: Random House. 1991

Rothstein, Natalie. Woven Textile Design in Britain to 1750 (The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Textile Collections series). London: Canopy Books. 1994

Scott, Phillipa. The Book of Silk. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. 1993

Thornton, Peter. The ‘Bizarre’ Silks. The Burlington Magazine Vol. 100, No. 665 (Aug., 1958), pp. 265-270, London.