In keeping with the arrival of summer in the Northern Hemisphere, last week’s Rate the Dress was a warm-weather frock, 1870s style, in white cotton brocaded in red wool spots.

Some of you said the spots made the dress look as if it had measles, and some of you didn’t like the polonaised poof of the bustle, and some of you didn’t like those oh-so-Victorian sloping shoulders (question: if you hate the mid-Victorian look for its sloping shoulders, do you also hate the 1950s New Look for its revival of the sloped-shoulder look?), and some of you didn’t like the black ribbon (which, incidentally, is my favourite part of the dress. It’s the little bit of sex in an otherwise almost too-sweet frock. It says “imagine if the neckline were here” or “tug me and see what happens” – still tasteful, but just naughty enough to add dimensionality to the ensemble 😉 )

But most of you liked the frock, really liked it in fact, giving it a total of 8.8 out of 10 (despite the occasional score of only 5) and keeping up the rather nice winning streak we’ve been having,

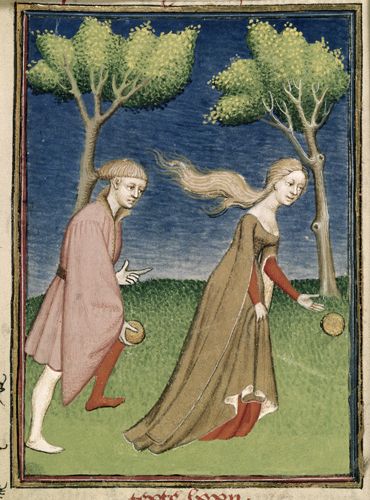

This week I really wanted to give you a depiction of a medieval garment to rate, but there just aren’t that many images of medieval garments that are large enough, detailed enough, interesting enough, and obscure enough. So I settled for very late-Medieval-rushing-through-Renaissance-with-a-smattering Tudor portrait of Johanna of Castille:

Joanna, noted both for her beauty and for her intelligence, before she became known for her madness (an indisposition that was suspiciously convenient for both her father and her husband, which I’m sure had nothing whatsoever to do with their determination to declare her mad and have her confined to a convent for the rest of her life so they could rule in her stead) was about 20 when this portrait was painted, and is depicted wearing a mix of romanticised costume, fashionable headgear, and status symbols.

The long, flowing skirt of Johanna’s gown looks back to medieval styles, and like her wide sleeves, provided an opportunity for the artist to meticulously render the sumptuous fabrics of her garments. The skirts may have been more fantasy than reality: other portraits of Joanna depict her in the fashionable Spanish farthingale that her younger sister Catherine famously introduced to England when she was married to Arthur. Her headdress is a current fashionable style, the black dye a particularly expensive colour, its severity serving to emphasise her noted looks.

The final piece to Joanna’s costume is her spectacular cloak, which presumably shows the coats of arms either of her titles, or of the nobles who owed her allegiance. The cloak increases the chances that the portrait was painted after July of 1500, when Joanna became heiress to the Spanish kingdoms after the deaths of her older brother, sister, and nephew. By this time Joanna had just begun to exhibit the first signs of what her family considered madness: religious scepticism, and an inclination to be lenient and liberal towards Protestants.

While probably not a strictly accurate depiction of Joanna, or what she wore, the Zeirikzee portrait is an excellent example of a the desired image of a Queen in the minds of the Spanish & Flemish: regal, elegant, devout, beautiful, fertile (note the emphasis on the roundness of her stomach), there to be admired, rather than to act.

So what does her outfit make you think of when you look at her? Does it appeal? A proper case of right royal raiment?

Rate the Dress on a Scale of 1 to 10.