In researching for the Historical Sew Fortnightly Challenge #6: Fairytale, I came across all the versions of Donkeyskin/Allerleirauh.

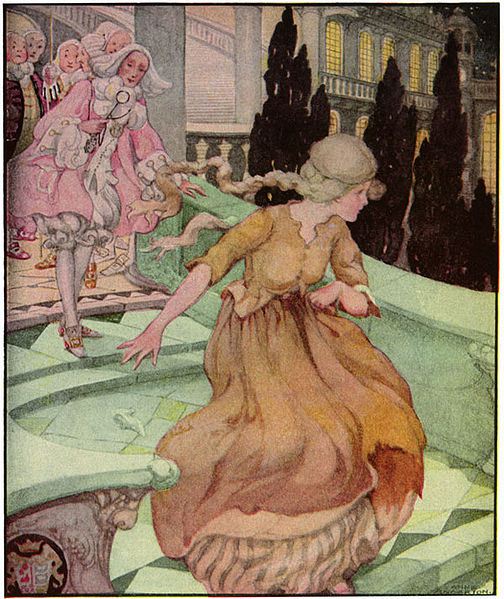

It’s an old fairy tale based around the premise that a Queen dies leaving a daughter, and her father the King declares/promises he will only marry a woman who is as beautiful/wise/kind/etc as his first wife. The daughter grows up and is the spitting image of her mother, so the King decides he will marry her (yes, really. It’s sometimes called The King Who Wished to Marry His Daughter). The daughter puts him off by saying that first she needs a dress as golden as the sun (or something equally as un-obtainable), and when this is procured, a dress as silver as the moon (ditto), and when this is managed, one as dazzling as the stars (you get the idea), and finally a coat made from the skins of one of each of all the birds and beasts that exist/the skin of her father’s prized donkey that poops gold (no, I didn’t make that up either!). When her father manages this she realises she can no longer put him off, so she stuffs her dresses in nutshells, puts on the coat, and runs off into hiding as a servant at another castle. There she goes to balls in the dresses and the prince falls in love with her and they marry. And they live happily ever after, more or less.

What I realised in reading these fairy tales is that they are very early examples of the way women are taught that we mustn’t say no.

Yes, we’re supposed to say no to drugs, and peer pressure, and excessive alcohol, and sex, but we still aren’t supposed to tell men “No.”

We aren’t allowed to say “No, you can’t have my number.” “No, I don’t want to dance with you.” “No, I won’t go out with you” much less the far worse, just plain old “NO” to any of those scenarios. Instead, we’re supposed to give fake numbers, to claim sprained ankles or that we’ve promised the dance already, to make up non-existant boyfriends, or say we are taking a break from relationships.

Donkeyskin is doing exactly this. Her father is demanding to marry her and she can’t say “Umm…you’re my dad and what you are asking for is horrible and dreadful, so NO!” Instead, she has to come up with excuses: I will once you have made me a nearly impossible frock. And another impossible frock. And an even more impossible coat.

Her dad wants to marry her! “No” should be more than sufficient!

Yes, I understand that in the context of the story she is buying time and trying to find a way out, and in the context of medieval society women had few choices, and it was hard to say no, but in modern society women are taught to give excuses, rather than a simple “No” – just as our crazy-skin wearing princess gives excuses rather than saying “No.”

Another example of not saying no is The Franklin’s tale, from Chaucher’s Canterbury Tales. Dorigen is happily married, does not want or encourage Aurelius, but is finally pestered by him so much that instead of saying no she gives a joking evasive answer of “I’ll sleep with you if this improbable thing happens.” Aurelius, of course, manages to make the improbably thing happen, and Dorigen has to face the consequences of her promise.

Now, my parents were really good at teaching me a lot of kinds of “No.” No to the aforementioned drugs/peer pressure/all alcohol/sex etc came easily to me. I was even good at the “No” to requests for phone numbers and dates and dancing. when I wasn’t interested.

But I wasn’t taught, and most women aren’t taught, to just say “No” to doing favours. We are told we always have to be there for friends, we have to be on every committee, plan every party, wear every dreadful bridesmaids dress, bake every batch of cookies for the school fair, help out at every stall, make every frock, and generally say “Sure, of course.” And if we really don’t want to, if we really can’t – we still can’t say no. We have to give an excuse. “Oh, that’s the same day as X”, “Sorry, but X has a cold”, etc, etc.

It was my friend Theresa of Existimatio who introduced me to the idea of just saying “No.” Not giving a caveat, not giving an excuse, just saying “No”.

She and I and Chiara of Ampersand and some other lovely ladies and even a few men sat around and discussed how to just say “No,” and how that would feel from both perspectives. Most of the ladies, and certainly myself, found the idea of just saying “No” hard to face. We’ve had so many years of societal pressure to be nice, and saying “No” isn’t nice. We’re supposed to soften it – to wrap it in sweet excuses. We’ll go as far as to go out with two phones – our ‘real’ phone, and a junk one, so we can give the junk ones number and not be caught out in a lie if they text it right away. The men pointed out that a blank “No” is nicer than a fake phone number. They also acknowledged, that some men, like Aurelius, are just dicks who won’t take no for an answer.

The solution to this is not to eventually give an excuse. In modifying our “No” to make it softer and more socially acceptable, some men come to think that “it is usual with young ladies to reject the address of a man whom they secretly mean to accept, when he first applies for their favour; and that sometimes the refusal is repeated a second or even a third time.”

Now, there is no excuse for men to not believe a “No”, however it is phrased, but not saying “No” didn’t help Dorigen with Aurelius, and nothing but a societal smackdown, no pretty excuses, is going to get those men to understand. We owe it to ourselves, and to men, to simply say “No”, when we aren’t interested.

Clearly the issue of men asking for phone numbers and dates is not one that troubles me much anymore – I have such an obvious excuse that I never feel obliged to give it, just a “No.” I’m taking the idea further and working on the other refusals in life: at learning not to give excuses or to say yes to requests for favours that I don’t actually have the time and energy to supply.

I’m not very good at it yet, but I look at Donkeyskin/Allerleirauh and I think “Sweetie, you really aren’t the best role model. Your dad just asked to marry you and you couldn’t just say “No.”

We don’t live in a fairy tale. We don’t live in the Middle Ages. Hopefully none of us will ever get put in a situation as dreadful as Donkeyskin/Allerleirauh’s, but even for the small unwanted situations, maybe we should think about just saying “No.”