Some of you asked how I did the Greek key motifs* on the 1905 Greek Key afternoon dress, so I thought you might appreciate some construction details in regards to the dress – both with the Greek key motifs, and other things.

When I first received the dress the motifs were applied with stitch witchery or some other sort of fabric adhesive, and since they were 20 years old, the adhesion was starting to weaken.

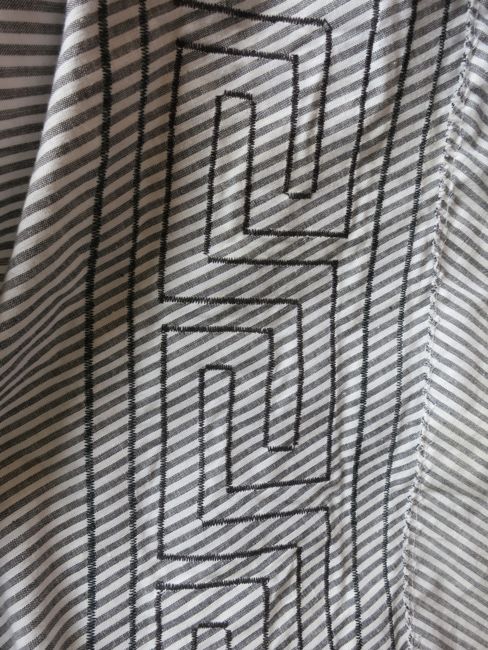

To strengthen the motifs, and finish the dress ‘properly’, I sewed them down using a very fine, tight zig-zag stitch on my sewing machine. I sewed along one straight edge, right to the outside corner, sunk my needle, and lifted and turned. At the inside corners I sunk my needle at the inside turn, and lifted and turned. This leaves a tiny square of un-sewn-ness right at each inside corner, but covers all the raw edges, looks neat and tidy, and is strong enough to last for another 20 years – or 80.

Doing this took A LOT of time. It also used A LOT of thread. 3 spools I think…

I used it as an excuse to use up all my random spools of black thread, and you can even see two different shades of black thread on the straight border applique and the greek key applique:

The outline of the applique stitching shows on the reverse of the skirt, and you can clearly see where I turned at each corner.

The hem motifs were a mend/job finish, but I completely re-did the yoke from the original. Here is what it looked like when it started:

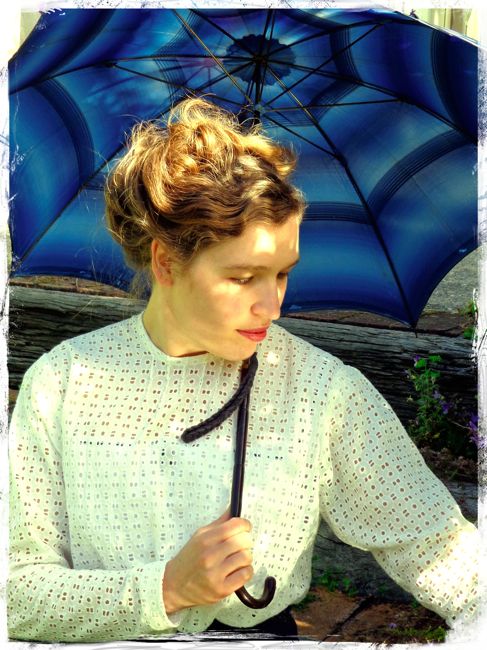

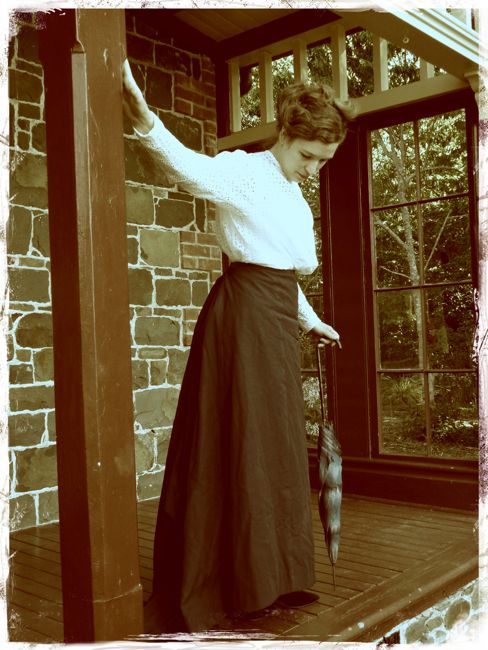

And my re-do:

I unpicked the original yoke, checked it against Janet Arnold to make sure that the pattern was true, and then used it to cut a new pattern out of white cotton sateen. I then stitched row after row of white cotton lace on to it, to imitate the effect of an all-lace fabric, such as was used in the original 1905 gown that Janet Arnold patterned.

Once again, lots of thread was used!

With the lace sewn down, I sewed on twill-tape channels for boning in the collar, and inserted the bones.

The back fastenings with hooks and eyes, so I used strips of scrap fabric to finish the raw back edges, and then hand-sewed on all the hooks.

I was really worried about the collar being too tight, so I over-compensated, and it was actually far too large on A, but I’ve just tried it on another potential model who is a wee bit taller and a wee bit bigger, and it fit much better.

The waist of the back hooks is covered with a velvet rosette. Arnold’s original actually has two small ones, but I forgot to check this as I was finishing the dress, and just made one large one to fasten the velvet sash I’d re-done.

I also re-did the sleeves from the first gown. I unpicked the the sleeves as they were, but rather than using them as a pattern I went back to Arnold.

I patterned out Arnold’s sleeves, using a base of the white cotton sateen, as with the yoke, and for the fabric, white lawn with pintucks and bias-ruffles, and rows of the same cotton lace as the yoke.

The fabric came pre-pintucked and ruffled, but with rows of nasty nylon lace, which I unpicked and replaced with the cotton lace.

The finished effect was, well, big. Quite a bit more poof than I envisioned!

I mentioned before that the big-ness of the sleeves bugged me, and you all assured me that it needs to be there, but I’ve figured out what’s wrong. It’s not that the sleeves are too poofy – it’s that they are too long. They should end at the models fore-arm, not her wrist. So I had a play yesterday, and I’m going to shorten the bottom ruffle a tiny bit, and the top poof a good few inches, and I think it will fix all the proportion things with the dress that are bugging me.

Still, tiny things aside, I think A looked gorgeous in it, and I do love it, both as it was, as it is, and as it will be!

And I hope you found some of the construction details useful.

*Of course, I didn’t actually do the Greek Key motifs – Pamela did years ago, and I just stitched them down