Brown linen is the term used to describe unbleached linen in the 18th and 19th century. ‘Brown’ linen could either be finely woven, high quality linen that would be bleached before being sold, or rough, coarse linen that would be sold brown.

Rather than pre-bleaching the linen yarn, cloth was usually woven brown, then sold to bleachers, the price based on the quality of the thread and weave, and then on-sold to fabric merchants and customers. Heavy and course linen would probably remain brown for use in cheaper clothes, as bags and for rough use (in 1803 Merriweather Lewis purchased from Richard Weavill, a Philadelphia upholsterer, 107 yards of brown linen to be made into 8 tents for his cross-continental exploration with William Clark), finer linen cloth would be bleached white.

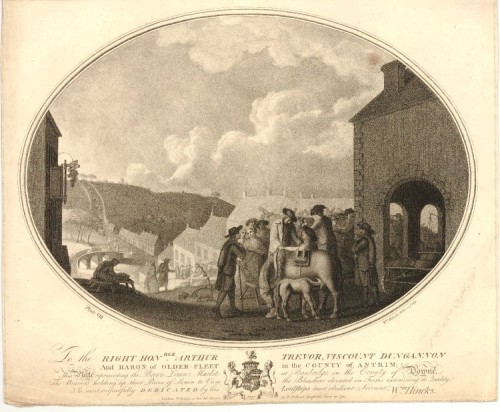

The Impact of the Domestic Linen Industry describes the how the town of Banbridge in the county of Down had grown up from a cluster of houses in 1718 to a prosperous market town 20 years later entirely around the sale of unbleached linen, and how “the weavers brought their webs to the weekly brown linen market, where dealers known as linendrapers purchased them for bleaching and finishing.”

Most of the mentions of specific brown linen garments in the 18th and 19th century come from two sources: lists of stolen clothings, and advertisements for runaway slaves in the American South. The latter is quite understandable: brown linen was a cheap fabric, so slaves, at the very bottom of the societal ladder, were most likely to be clad in the cheapest cloth. Mentions of stolen clothing are more interesting, because they illustrate how valuable fabric was in the 18th and early 19th century, when even a “man’s shirt of brown linen much clouted and worn” was worth stealing in the 1760s.

In July 1804 a slave named George fled Charleston in “brown jacket, brown calico waistcoat, and brown linen pants with suspenders.” Three decades later one Willis ran away via steamboat from New Orleans wearing “white shirt, brown linen pants, a blue frock coat and a black hat.”

In the 18th century the brown linen worn by slaves for shirts, chemises, petticoats and summer clothing was invariably osnaburg (also spelled ossnabriggs or oznabig). Onsaburg is a heavy, coarse plain-weave fabric having approximately 20-36 threads per inch. The name coming from the German city of Osnabrüch where a course linen cloth was manufactured in the early 18th century. By 1740 osnaburg was being manufactured in Scotland and by 1758 2.2 million yards were being made, mainly for export. Some was exported to England or the continent, but most went to the Americas, and most of that was used for clothing for slaves.

It was so popular for cheap labourer’s clothing that when cotton replaced linen as the most economical fabric in the early 19th century the name became applied to a cheap cotton fabric of a similar weight and weave. An 1835 story describes a slave wearing an “onsaburg chemise and coarse blue woolen petticoat”. Similarly in 1853 The Lofty and the Lowly mentions a similarly dressed woman in an “osnaburg chemise, and linsey-woolsey petticoat.” By this time onsaburg could have been either linen or cotton. Onsaburg is still readily available (Jo-Annes in the US sells it) for those wanting to replicate early 19th century lower-class in America.

Cotton onsaburg for sale here

Unbleached linen was commonly called brown linen well into the mid-19th century. In 1824 “brown linen cambric” was advertised for sale in the New England Farmer, and in 1840 The Workwoman’s Guide describes “A Gentleman’s Worshop Apron…of Holland or strong white or brown linen.” In 1835 the British government passed “An Act to continue and amend certain regulations for hempen manufacture in Ireland”, which frequently describes “Brown or unbleached or unpurged linen yarn” and proscribes the measurements of cloth “when brown and before the same shall be bleached.” Brown linen was sold in New Zealand in the 1860s. Even as late as 1895 the Montgomery Ward & Co. catalogue was selling “brown (unbleached) linen” in 50 yard lots. By the mid 19th century the brown linen that is being sold is clearly intended to be used only as rough cloth.

Brown linen finally ceased to be a poor-mans cloth in the later 19th century with innovations in bleach technology and the rise of cotton as the cheapest, most readily available fabric. Improved bleaching technology throughout the early 19th century made it so much cheaper and easier to bleach linen that white linen of the same quality was hardly more expensive than brown. In the first part of the 19th century the cheapest bleaching methods weakened the cloth and people “loudly complain of the rotten state of the linens being retailed in a grey [partly bleached] state in the streets, alleging they give no wear from being bleached with lime.” By the end of the century white linen was as common as brown, and cotton was a far cheaper fabric than linen, so linen of all colours achieved a bit of status and unbleached linen suits and dresses were worn by the wealthy for summer clothes.

Day dress of unbleached linen with green silk underslip, 1901-2, Misses Leonard, St. Paul, US, Minnesota Historical Society

Sources:

Crawford, W.H. The Impact of the Domestic Linen Industry. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. 2005

Embleton, Gerry and May, Robin. Wolfe’s Army. London: Osprey Publishing. 1999

Franklin, John Hope and Schweninger, Lauren. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999

Katz-Hyman, Martha B, and Rice, Kym S. (eds). World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the US. Santa Barbara California: Greenwood, 2011.

Saindon, Robert A (ed.). Explorations Into the World of Lewis and Clark, Volume 2: Essays from the pages of We Proceed On: the Quarterly Journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. “Along the Trail”. R.R. Hunt. Great Falls Montana: Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. 2003

Styles, John. The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. 2007

The workwoman’s guide, containing instructions in cutting out and completing articles of wearing, 1840.