My next class at Made on Marion is a full skirted, 1950s dress class.

Why?

Because full skirted dresses are awesome and gorgeous and fun to wear.

However, they can also be a little tricky to make.

How to gather all that fabric in, get the hem of a circle skirt to be perfectly even, fit the bodice? Does it need boning? What about a petticoat, and what kind? What about horsehair at the hem? Will it work for a border print? What about a directional print? A class is the perfect way to work through that, whether you have a vintage 1950s pattern you want to tackle (and maybe need to size up from a 32 bust to a 36 bust!) or a modern reprint of a vintage.

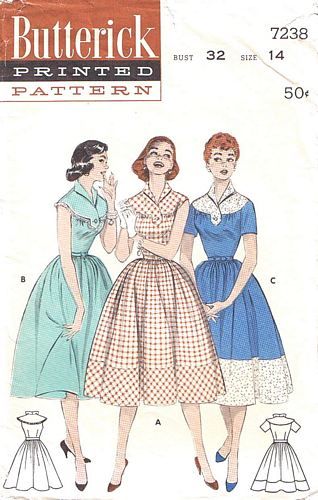

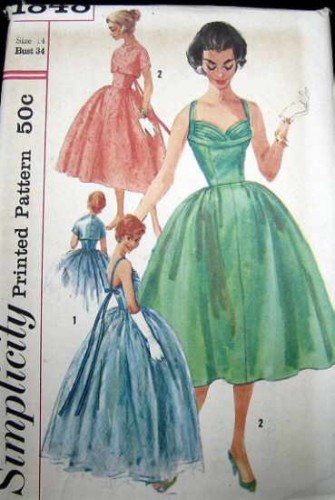

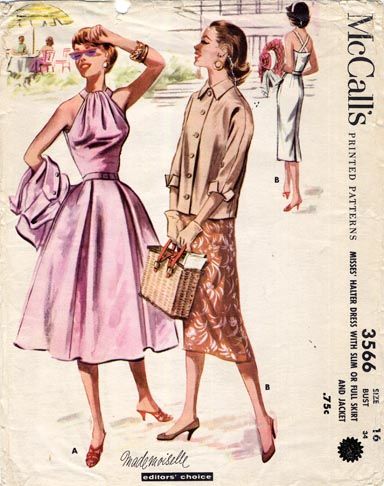

To inspire prospective students, here are a few of my favourite 1950s patterns, some of which I own, some of which I don’t:

I just got this one. Look at the gorgeous nautical detailing:

The pattern envelope describes this as “A dress to be worn with a light heart, a light step”. <3

The low back is so ‘on-trend’ right now, and this dress is such a classy way to do it. Also, that pleated skirt? Swoon!

This sexy dress is ‘Easy to Make’, and the overlapping front pleat is tres chic.

And for really sexy and gorgeous, try this dress. Ooh la la!

I love the simple halter on this, and I love, love, love the pleated skirt. A great alternative if circle skirts aren’t your best look.

If vintage patterns are too scary or scarce, you can always go with one of the fabulous reprints that Vogue are putting out:

Mmmm….stripe matching!