I’ve been thinking about body shapes and clothes and colours, and what is flattering recently.

It started with an offhand comment someone made about circle skirts, and how they are flattering on everybody. Totally not true. Circle skirts are one of my worst looks. They emphasize my thick waist and short torso, make me look very pear-shaped rather than a tiny bit pear shaped, hide my awesome bottom (which I quite frankly love), and, in short, don’t look nearly as good as most other shapes do on me.

I’m not saying I look really bad in them: just that they bring the focus to all my least favourite bits and hide all my most favourite bits (ahem. bottom.), so they aren’t flattering.

So, anyway, here are five things that are frequently held up to be universally flattering, but which I think look good one some people, and not on others, because hey, we all have different shapes and faces and skins and figures. But that’s just my opinion.

- Black

Black does not look good on everyone. Sorry, it simply doesn’t. In fact, I think that black is actually slightly unflattering on more people than it is flattering. With that said, there are different shades of black, and different fabrics will reflect light differently, and it can change depending on whether the black is up around your face, or cut lower over your chest (which is a different skin tone). Black tends to be particularly unflattering with pale winter skin and muted, dull, winter light. And when does everyone wear black? Winter! So bad!Black does, however, look awesome on me. It’s one of my best colours. This is something I really struggle with, because it feels so boring to just wear black all the time when there are all these amazing colours, but I also know that it makes my skin glow and turns my hair to gold and hey, I’m vain (well, is it really vanity if you want to look gorgeous all the time, but also want everyone else to look gorgeous, and don’t even mind if they look more gorgeous than you, as long as you look your best?) so I kinda do want to wear it all the time.

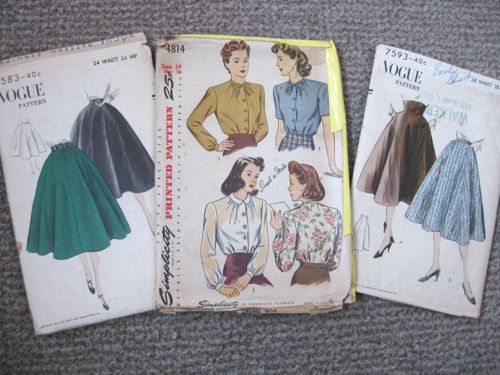

- Circle skirts

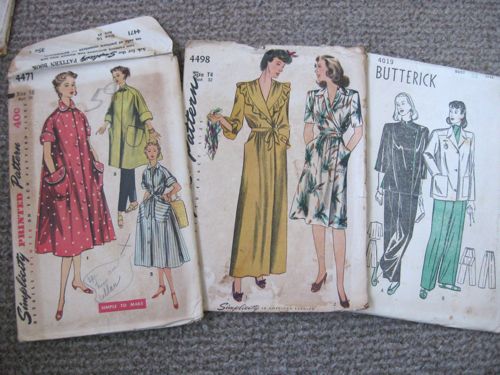

Good on many figures. Not the best look on slim waistless figures, or if one of your best assets is your…ummm…ass. - Wide belts

Why, oh why, do all those ‘how to dress’ shows keep telling women how awesome these are? What a great way to thicken your waist and cut your figure in half! Some women do look great it them. Just not all. They are terrible on me. I do love a good thick sash though (see the photo that goes with entry #1)! - Wrap tops.

So good on some women. So very, very, very bad on me. I just look no breast, all ribcage, and I see the same effect on lots of other women. - Strapless.

True story: When I was wedding dress shopping (before I decided that time or no time, making a dress would be less of a headache) I asked to only try on non-strapless dresses. This isn’t because I don’t look good in strapless dresses (I look great in them), but because I was stuck on being different (insert eyeroll here). Anyway, one wedding dress consultant told me that “no one will know you are the bride if you don’t wear a strapless dress”. (really? Who else is planning to show up in a fancy white dress and might be confused with me, only their dress will have straps?). Every other wedding dress consultant when on and on about how flattering they are. It’s not that they are flattering: it’s just that that is what most manufacturers make. And not only are strapless dresses not the best look on everyone, a badly fitted strapless dress is just about the worst look you can wear. It makes me sad.

So what do you think? Have I just committed total fashion/sewing heresy? What have I missed? Do you like the way you look in these things, or not?