The burnous, both in name and design, is of Arab origin, and describes a full, hooded cloak, often decorated with embroidery and tassels.

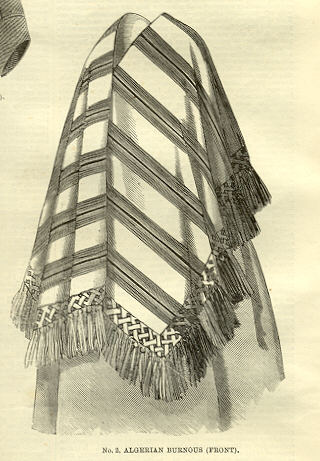

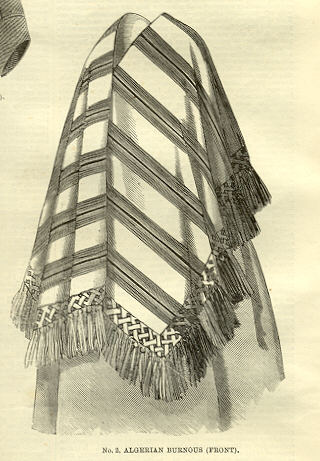

Algerian burnous from The Queen Magazine, August 30, 1873, via Koshka the Cat

It can also be spelled burnoose and bournouse.

The burnous was introduced to Western fashion through the Spahi, the French calvary troops of from Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, whose uniforms included burnous. The Spahi began in the 1830s, and saw extensive action throughout the 19th century. This, combined with photographs of the Spahi troops in their burnous taken by Roger Fenton in the 1850s popularised their image in the West, and started the fashion for the cloaks.

![Zouave & officer of the Saphis [i.e., Spahis] Zouave, full-length portrait, seated, facing right and Spahi officer, full-length portrait, standing, facing left. Date Created:Published- [1855]](https://thedreamstress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Zouave-officer-of-the-Saphis-i.e.-Spahis-Zouave-full-length-portrait-seated-facing-right-and-Spahi-officer-full-length-portrait-standing-facing-left.-Date-CreatedPublished-1855-.jpg)

Zouve & officer of the Spahi in a burnous, Roger Fenton, 1855

Burnouses fit well with mid-19th century fashion, as the loose shape was easy to wear over large hoopskirts, and the hoods mimicked the bonnets that were worn with daywear, or could even fit over the bonnet.

The Bridesmaid by George Baxter, Print, England, Britain, 1855, V&A

A 1859 fashion article describes burnouses:

These are made frequently in cachemire, in broad Algerienne stripes, or in light coloured cachemire, wadded and trimmed with plaid, and also in black silk trimmed with plaid, or plain velvet, plaited ribbon and silk, or handsome passementerie. When trimmed with moire the lining should be of the same colour.

Burnous of white and green stripes with green velvet tassel and bonnet over green silk gown. 1850s

Throughout its history in Western fashion the burnous retained an exotic flavour, emphasised by the use of Eastern fabrics, the aforementioned “Algerienne stripes”, tassels, and Indian embroidery.

Child's cape. Twilled peacock blue woollen cloth, embroidered in cream silk thread, with a cream tassel on the hood; Anglo-Indian, 1860-70, V&A

The shape did alter with fashions. Burnouses became shorter and less voluminous as the hoopskirt went out of fashion and the bustle came in in the 1870s.

Seaside burnouse, The Queen Magazine, August 30, 1873, via Koshka the Cat

The burnous saw a decline in popularity in the 1880s and 1890s, and the more fitted and structured silhouettes of fashion demanded more structured garments (such as the paletot). It might have fallen out of fashion entirely were it not for the Aesthetic movement and the emphasis in aesthetic dress on ethnic inspiration and looser silhouettes.

Burnous by Liberty & Co. Ltd.,1905-1916, Wool and machine-embroidered trim, V&A

They remained popular in the early 20th century along with the overall fashion for exoticism. Burnous cloaks were often patterned with ‘Eastern embroidery” to emphasise the exotic effect, though art nouveau inspired designs were also popular.

Liberty & Co. velvet burnous, c.1900. via Vintage Textile.com

Burnouses were mainly a Victorian and early 20th century garment, but they have made sporadic returns throughout the 20th century. A 1937 fashion article describes:

…the new burnous cape, draping into a hooded swath at the back and tied at the front neckline by matching coloured silk cords…these burnous capes fall gracefully down the back, where they finish at half or full length

Sources:

Johnston, Lucy. Nineteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishig, 2005

O’Hara, Georgina, The Encyclopedia of Fashion: From 1840 to the 1980s. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. 1986

![Zouave & officer of the Saphis [i.e., Spahis] Zouave, full-length portrait, seated, facing right and Spahi officer, full-length portrait, standing, facing left. Date Created:Published- [1855]](https://thedreamstress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Zouave-officer-of-the-Saphis-i.e.-Spahis-Zouave-full-length-portrait-seated-facing-right-and-Spahi-officer-full-length-portrait-standing-facing-left.-Date-CreatedPublished-1855-.jpg)