While a la mode may mean ‘in the fashion’ it was also once the name for a fabric.

In the 17th, 18th & 19th century alamode was a thin plain tabby weave lustred silk, usually black. It was used mainly for mourning, and for the linings of expensive garments, as well as as the outer fabric, especially for outerwear such as hoods and mantuas. A 1691 theft included “”two blacke allamode hoods worth 5s”. Eighty years later, in 1770 Mary Berridge’s London house was broken into, and one of the items stolen was “One Black Allamode Clock Lined in the Blue Latestring”

In early histories of 18th century fabrics it is described as being like lustring or surah silk, but more loosely woven (which may be a very non-technical way of saying that it is a plain tabby weave, rather than a twill like surah), and some references even describe it as the same fabric as lustring, but period advertisements make that very unlikely.

While usually spelled allamode or alamode, the vagaries of 17th and 18th century spelling have also given us the options of elamond, ali-mod, olamod, alemod, arlimode, and ellimod.

Alamode arose as a term in the last quarter of the 17th century. A 1676 edition of the London Gazette lists:

“Several Pieces of wrought Silk, as Taffaties, Sarcenets, Alamodes, and Lutes.”

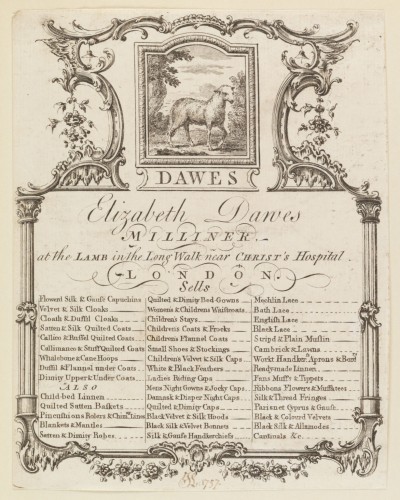

The reference to ‘Lutes’ makes it clear that alamode was a different fabric to lustring. Another reference, a slightly later trading card also lists alamodes and lustrings (lutestrings) as different fabrics.

There aren’t a lot of references to the possible end uses of alamode in the 17th century, though there are a few hints. The minutes of the London Court of Governors from October 1694 tell a tale of a 17th century scam, and what the fabric was intended for:

Sarah… accused by Edwd. Fellowes for falsly and fraudulently coming into his Masters Shopp in the name of Mr. Thompson with a designe to cheat him of some Allamode Silk to make a hood and Scarfe prtending that Mrs. Thompson, her late Mrs. had sent her with a Counterfeit Note wth.

Alamode, along with all sorts of clothing and fabric (my how times have changed!) was a popular target for thieves. A 1696 account tells of a much grander theft than Sarah’s failed attempt:

Stolen out of a Wagon at the Cock Inn in Wooburn in Bedfordshire, on Thursday night the 25 past, a Truss in which was about £165 in old. Money, and other parcels of Money, in which was 31 Guineas, and one Broad Piece of Gold ; also one Piece of broad Allamode, and one Piece of Narrow Allamode Silk ; two Pieces of Black Silk Crape; Half a Poimd of fine white Thred ; one Piece of Linen Cloth, and other things out of the same Truss. Also out of a Box, one plain Muslin Head Dress, and one striped Muslin Head Dress. And also out of a Bag, half a dozen pair of RoU Stockins, and 18 pair of short Stockins.

The mentions of broad and narrow widths are fascinating. Did they just refer to widths, or do the descriptions also indicate other differences?

References in the early 18th century indicate that it was a specifically English silk, part of the English monarchies haphazard attempts to compete with the French fashions and the European textile industry. When William of Orange died in 1702, the mourning dress of Anne’s court took an interesting turn:

For the encouragement of our English silk, called a-la-modes, his Royal Highness the Prince of Denmark (the Queen’s husband) and the nobility appeared in mourning hat-bands made of that silk, to bring the same in fashion in the place of crapes which are made in the pope’s country, wither we send our money for them.

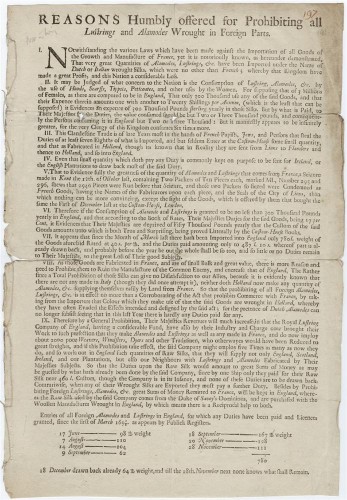

All alamode may not have been English though. The Boston News Letter of September 15, 1715 gives an advertisement for “Allamods French and English.” And the elaborate 1691 “Reasons humbly offered for prohibiting all lustrings and alamodes wrought in foreign parts” makes it clear that alamode did not necessarily indicate an English fabric, but that England was simply banning the import of foreign alamode.

1691 "Reasons humbly offered for prohibiting all lustrings and alamodes wrought in foreign parts." Lewis Walpole Library

Whether or not it was made in England, alamode was sold throughout the English colonies. As early as 1687 Judge Sewell ordered it from England for his wife’s wardrobe. A decade later a citizen of Massachusetts left 20 ells of allamode in his will. Advertisements for it are found in Nova Scotian newspapers of the mid 18th century. In April 1774 the Boston Gazette carried the following notice:

Caleb Blanchard…Begs Leave to inform his Friends and Customers, That he has Imported by Capt. Symmes, from LONDON,

A Fresh Assortment of Summer GOODS, which he will sell at the very lowest Prices for ready Money viz. Dutch Laces, Cheavaux de Frize & Blond Laces, Gauzes, Gauze Handkerchiefs, a fine Assortment of Callicoes, &c. India Dimothys, Jackonet, sprig’d and striped Muslins, Bengals, Nankeens, Lungee Romalls, black and blue Ostrich Plumes, Skeleton & Cap Wire, Allamodes, Sarsnets,Ribbons, Gown Trimmings Hoses, best Pumps, Silk ditto, Girls & Misses Morracco Pumps, Cambricks, Lawns, a fone Assortment of Mens & Womens Worsted, Thread & Cotton Hose, Breeches Pieces, Morris’s Patent Gloves and Mitts, superfine and other Cloths, Duroys, W?ltons, Serges, Ravens Duck, Dowlass, China Ware, Paper, Nests Red Trunks, Irish Linnens of all Widths, Spices, &c. &c &c.

While all alamode may not have been English and supporting the English economy, at least part of Anne’s ploy worked, and the fashion for alamode as mourning attire was set. In 1752 a trading card for a London undertaker waxed enthusiastic about his wares:

Velvet Palls, Hangings for Rooms, large Silver’d Candlesticks & Sconces, Tapers & Wax Lights, Heraldry, Feathers & Velvets, fine Cloth Cloaks. . . . Rich Silk Scarves, Allamode & Sarsnelt Hat Bands, Italian Crape by the Piece or Hatband, black & white Savours, Cloth Black or Grey, Bays & Flannel. . . . Burying Crapes of all Sorts, Fine Quilting & Quilted Matrices the best Lac’d, Plain & Shammy Gloves, Kidd & Lamb. . . . All Sorts of Plates & Handles for Coffins in Brass, Lead or Tin, likewise Nails of all Sorts. Coffins & Shrouds of All Sizes ready made.

In the 1770s a funeral bill in Massachusetts included costs for “15 best rich allamode silk hatbands.”

Woman's hat, black silk (almost certainly alamode), 1770-1780 via Colonial Williamsburg, accession # 1993-335

Beyond a lining fabric and a replacement for mourning crepe, alamode had one last use. There are references to alamode fringing, but what it was, and what it looked like (other than a fringe) is not entirely clear.

Elizabeth Dawes, milliner, at the Lamb in the Long Walk near Christ's hospital, London ca 1757, Lewis Walpole Digital Library

Sources:

Buck, Anne. Dress in 18th Century England, B.T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1979

Cummings, Valerie. Royal Dress, B.T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1989

Earle, Alice Morbe. Costume of Colonial Times, Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York. 1917

Heel, Ambrose. London Tradesmen’s Cards of the XVIII Century; An Account of their Origin and Use. Dover Publishers: New York. 1968

Navas, Deborah. Murdered by His Wife. University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst. 1990

Van der Zee, B, and Henri Van der Zee. William and Mary, Knopf: New York, 1973

On the internet:

18th Century Life. The Boston Gazette.

Essex Record Office. Calendar of Essex Assize File [ASS 35/132/1] Assizes held at Chelmsford 2 March 1691

London Lives: 1690 to 1800 – Bridewell Royal Hospital: Minutes of the Court of Governors. 6th January 1689 – 8th August 1695. 12 October 1694.

Phrases.org.uk – A la Mode