Latest Posts

Jeanne Samary and the ballgown of 1878

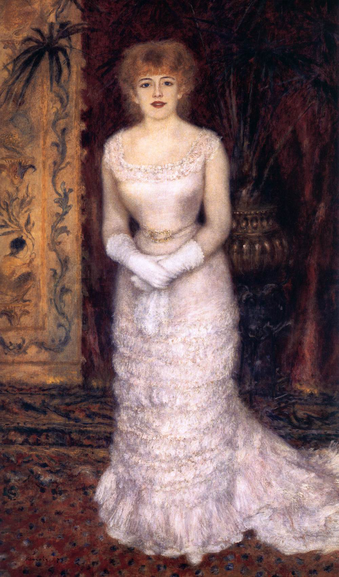

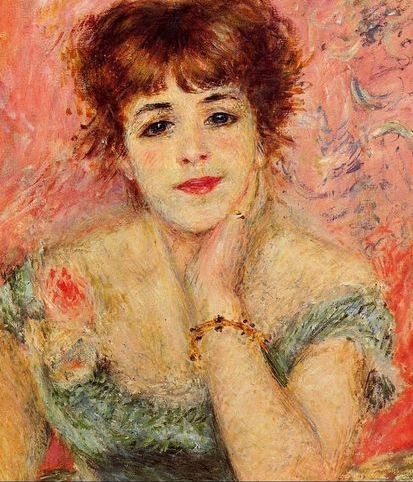

‘Jeanne Samary Week’ (like ‘Shark Week’, but with cuter teeth) was inspired by a question about Jeanne Samary’s dress in Renoir’s full length portrait of her:

I recreated the dress, and a reader wanted to know about the original gown. Who made it? What did it look like? Did it actually exist?

This is my interpretation:

Clearly I don’t have Samary’s enviable figure, but in all other ways I’m happy with my dress as a recreation of what Samary’s dress might have been.

So, what do we know about Samary’s actual dress?

Well, for one, it probably existed. Renoir was known to paint dresses that did exist, and did belong to the models he knew. The same frocks are repeated in various paintings in numerous paintings by Renoir and other Impressionist artists. Samary, for example, is shown in the same dress in The Swing and dancing in the Bal du moulin de la Galette, and Renoir and Monet both painted Monet’s wife Camille in a blue robe/tea gown. And, as seen in Tuesday’s ‘Rate the Dress’ Samary was painted in outfits that really existed.

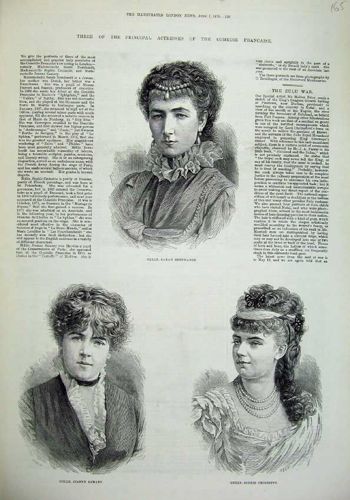

There is also a sketch of Samary that seems to show her in the same frock:

I love the details of the white lace around the neck and sleeves, and also, that the sketch clearly shows her holding a Japanese fan, which is exactly what I thought would go with her dress!

Based on comparison with fashion plates and with other paintings, we can assume that the gown is an evening gown, worn to balls, the theatre, and salons. Numerous paintings of the era show the sleeveless frocks in these settings. The more commonly seen 3/4 length sleeves, low square necked dresses were reception gowns. How women danced in the long sweeping trains is a wonder!

There is one painting from 1878 that shows women in similar dresses at a salon:

And Mary Cassatt did three works from the era with women in these type of gowns at the theatre:

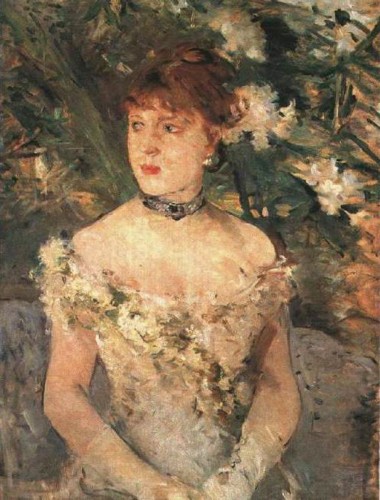

It’s clear that Samary favoured this style and cut of gown, as the same cut is seen in Reverie.

We don’t know who the dress was by. It might have been a Worth, but there were any number of other dressmakers operating in Paris in the 1870s.

We can gain insight into Samary’s dress by looking at paintings from the same era as Jeanne Samary’s portrait that also depict women in evening gowns.

The neckline in this dress is more off the shoulders than Jeanne’s almost square-necked dress, but the front ruching is similar, and the treatment of the train is eerily similar to what I have done (I wasn’t familiar with this work when I made my Jeanne dress)

The pink frock has a back neckline which indicates that it was somewhat closer to Jeanne’s dress, and the general silhouette of the dress is also similar. Plus, it gives a lovely glimpse of the shoes!

For a detail of ballgown bodices circa 1878, we can look at a work by Morisot:

Or one by Sargent:

It’s interesting that Jeanne’s dress is completely devoid of flowers, as these seem to be such a feature of other evening gowns of the era.

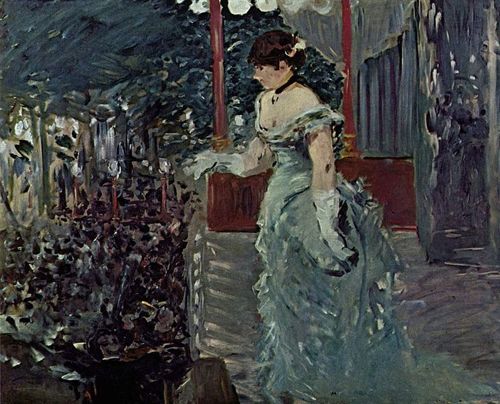

As well as depictions of wealthy society women, there is even a painting of another stage personality in an evening dress/ballgown:

In Manet’s work we see the lovely roundness of front and back that were so typical of corseted figures at the time. We can’t tell what Samary’s side figure looks like in her portrait, but it is reasonably to assume that she would also have had the lovely swell below her waist: not my flat front.

Finally, moving a little latter in time, another work by Renoir shows us the back view of a dress similar to Samary’s.

Jeanne Samary and her life

A reader has asked me about Jeanne Samary, and the real dress that she would have worn for Renoir’s full length portrait.

This is what we know about Jeanne, and tomorrow I’ll discuss what other garments of the late 1870s tell us about Jeanne’s dress, and who it might have been made by.

Jeanne Samary was born on 4 March, 1857 (making her in her early 20s when she sat for Renoir). She came from a strong musical and theatrical background: her father was a cellist, and two of her maternal aunts, as well as her grandmother, had been actresses.

The artistic and dramatic gene was strong in Jeanne’s generation. Her older sister Marie also became a noted actress, appearing at the Odeon and Renaissance Theatres, and was painted by Jules Bastien-Lepage. Her older brother was a famous violinist, and her younger brother Henry, a noted actor who was painted by Toulous-Lautrec.

Jeanne’s mother is a shadowy figure at best, and not much is known about her childhood, but it can’t have been easy. Her father was noted for his incessant hand washing, and almost certainly suffered from OCD. What affect this had on the young Jeanne is unknown: it may have prompted her desire for fame, and the security and independence that came with it.

At 14 Jeanne entered the Conservatory, and at 18, in 1874, she won first prize for her comedic acting. That year she debuted as the servant Dorine in Tartuffe at the Comedie-Francaise, and while moderately well reviewed, she did not immediately receive the acclaim that she hoped for. After Tartuffe, Jeanne was cast as a servant in a series of Moliere plays.

While enjoying success and recognition as a comedic actress, Jeanne hoped for more substantial and prestigious roles. She did not want to be eternally characterised as “stout, pink, and merry” as the newspapers described her in her maid’s costume.

In order to advance her career, Jeanne began working as a model. Her ambition appears to have been to be painted in the same style as Sarah Bernhardt, in order to attract the same type of dramatic, tragic roles which received greater respect.

Jeanne’s quest was off to a good start when, at salon held by the notable Madame Charpentier, she attracted the attention of the newly famous Renoir, always an aficionado of beautiful young women (particularly curvaceous strawberry blondes).

She featured in Renoir’s 1876 work The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette and was the main subject of The Swing, also done that summer. Alas for the ambitious Samary and the only recently lauded Renoir, both works were derided for the critics for their sketchy brushstrokes and intentionally patchy light, and neither served to launch her as a notable beauty. Further images of her were received in a similar manner.

At some point around 1877, Samary almost certainly became Renoir’s lover, a move commemorated in the little known The Dreaming Woman. Samary disliked the painting, and felt that it made her look common and slovenly. Using her new influence over Renoir, she was able to convince him to paint two portraits of her in the style that she wanted: elegant, glamorous and dressed to the nines. Whatever Renoir’s reasons for his two portraits of Samary, her motivation was likely more career based than art based.

Unfortunately for Jeanne’s ambitions, neither portrait was a success with the critics and the general public. Part of this was bad luck and bad placement. Renoir’s friends who saw the full length portrait of Jeanne in his studio were enthralled. Cezanne raved “Renoir created the image of the Parisienne”. In contrast to its central placement in Renoir’s studio, the painting was placed very high on the wall at the Exhibition of 1878, and was surrounded by other works in a small room, where viewers were unable to see it properly. The best review it got as a description as “an entertaining portrait.”

Tired of each other’s agendas, Samary and Renoir parted ways in 1880. Renoir went on to pursue Aline Charigot (also the subject of one of my recreations) and Samary to woo a more technical, academic painter.

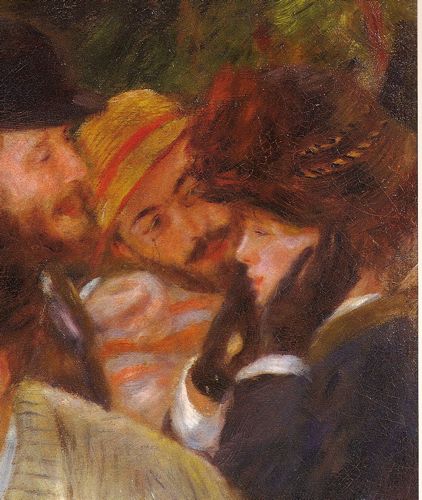

The cooling between Samary and Renoir is noticeable in The Luncheon of the Boating Party, where Samary appears in the far back of the painting, her face mostly obscured by her hat and hands, and her attentions devoted to the two men who flirt with her. Renoir’s new flame and future wife Aline, on the other hand, figures prominently in the forefront of the painting as she plays with her dog.

Luncheon of the Boating Party (detail), Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1879, The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

Samary’s hopes of being launched by a fabulous portrait were never realised, despite attempts with other painters. She appeared to have specifically picked painters who had depicted the ‘Divine Sarah’, who she hoped to emulate. She tried with Jules Bastien-Lepage (who also painted her sister Marie), but Bastien-Lepage never became as noted as Renoir.

She was painted in 1880 by Louise Abbema, another strategic choice as Abbema’s 1875 portrait of Sarah Bernhardt received widespread acclaim, but once again, Samary was not as lucky, and a later Abbema portrait was even less successful.

Portrait of Jeanne Samary, Louise Abbema, 1880

In 1882 love, or perhaps the realisation that a sparkling career at the pinnacle of theatre and society were not to be hers, convinced her to marry the wealthy society man Paul Lagarde. Her romance and marriage to Legarde were certainly spectacular and finally allowed her a dramatic role, though it was a real life one, rather than onstage.

Legard was head over heels for the pretty actress, and pursued her ardently, but his society parents were horrified that their son would consider marrying a common actress (especially one who may have been the lover of an artist!). His father even tried to have the marriage prevented on legal grounds, and when that did not succeed, they refused to attend the marriage ceremony.

History is silent on whether the birth of three granddaughters, one of whom sadly died in infancy, softened their attitudes. Perhaps not, as both surviving girls went on to be actresses like their mother.

Samary appears to have found happiness as a wife and mother: in 1890 she wrote a children’s book Les Gourmandises de Charlotte which was illustrated by the noted cartoonist and children’s illustrator Humphrey Jacques de Breville. The book was popular, but tragically Samary did not live to enjoy success at last: she succumbed to typhoid in the same year.

It’s not clear how Samary felt about Renoir’s portraits and her other paintings beyond their unsuitability for publicity. According to some accounts, she kept Reverie and displayed it in her apartment, and it was cherished by her husband after her death. What we do know is that many of the works she appeared in have gone on to become some of the most recognised and beloved Renoir paintings, allowing her to finally achieve the acclaim and immortality she longed for.