I’ve got a new Scroop Pattern ready to be tested!

The Pattern:

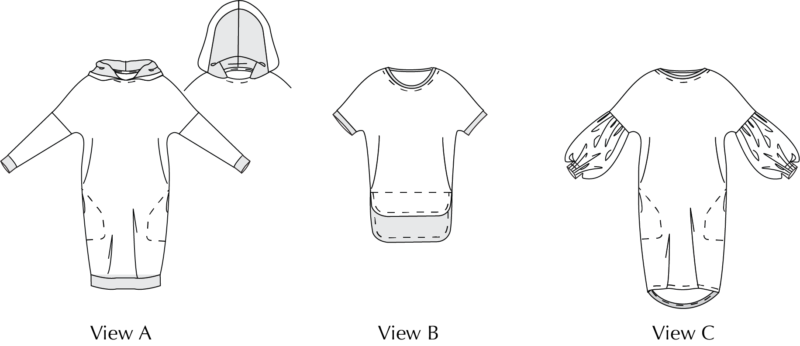

This is my lockdown pattern: a design I created that’s as warm and cozy as a hug. It feels like wearing pyjamas, but fabric choice and finishes can take it from weekend casual to work appropriate to evening glam.

It’s a versatile drop-shoulder dress and top designed for midweight knits. It has three different necklines (hood, shallow scoop, scoop), three different sleeve options (long knit, full woven sleeves with gathered cuffs, or short) and three hems (knee length with a knit band, shirt length with a curved hem, longer in back, and knee length with a dropped hem)

Testers:

For this pattern I need testers who are low-intermediate or higher level sewers with some experience sewing knits.

You will also need to:

- be able to print patterns in A4, A0, US Letter or US full sized Copyshop paper sizes

- have the time to sew up the item if you agree to be a tester for it

- be able to photograph your make being worn, and be willing for me to share your photos on this blog and instagram.

- be able to provide clear feedback

- be willing to agree to a confidentially agreement regarding the pattern

- have a blog or other format where you share and analyse your sewing

I would hugely appreciate it if you would share your finished make once the pattern launches, but this is not mandatory. I’m asking for TESTERS, not marketers. The requirement of a blog/other review format is to help me pick testers. I want to be able to see how you think about sewing, and that your experience level matches up to the pattern.

As always I’m be looking for a range of testers, in terms of geographical location, body type, sewing experience, and personal style.

There will be a Facebook group for the testers: joining it is optional.

The Materials:

I’d like to start testing in less than a week’s time, so I’d recommend that you already have the materials needed on hand if you apply to be a tester.

Body all views, sleeves views A & B, hood view A: midweight knit fabrics with 35-50% stretch, including midweight jerseys, lighter weight sweatshirting, waffle knits, heavier merino knits, etc

Cuff & neck bands, all views: midweight knit fabrics with 35-50% stretch and good recovery.

Hood lining View A , hem facings view B & C: light-midweight knit fabrics with 25-50% stretch.

View C sleeves: lightweight woven fabrics such as chiffon, crepe de chine, rayon challis, voile, etc.

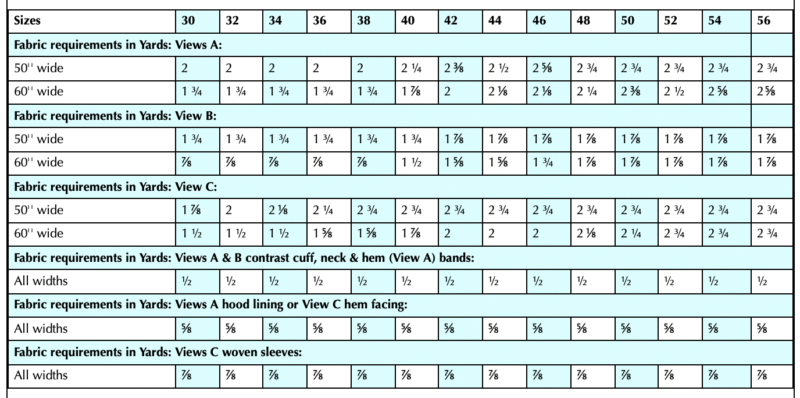

Fabric Requirements in Yards:

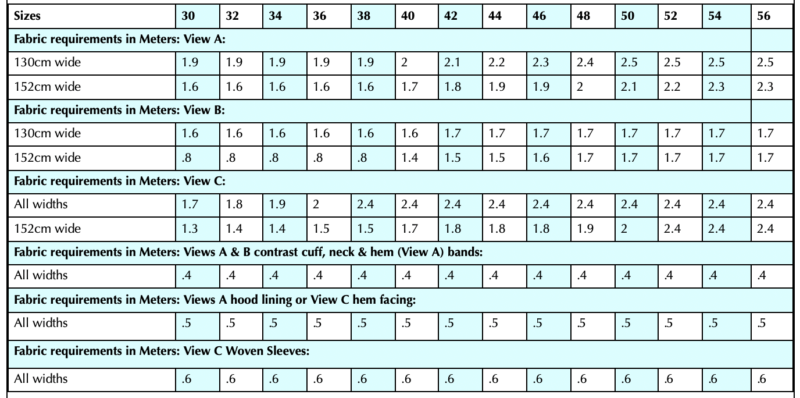

Fabric Requirements in Meters:

The Timeline:

Because this is a very quick make, I’m doing this on a fairly compressed timeline.

Materials:

If you’re selected to test I’ll let you know and send you the full materials requirements, line drawings, and the full pattern description on, by 5pm NZ time on Wed the 12th of Aug (Tue the 11th for most of the rest of the world).

Patterns:

I will send out a digital copy of the pattern to testers by 5pm NZ time on Friday the 14th of August.

Testing & Reviewing:

Testers will have until 6pm NZ time on Mon the 25th of Aug (11 days, with two full weekends) to sew their make, respond to the testing questions, and take photos.

What you get:

Pattern testers will get a digital copy of the final pattern, my eternal gratitude, and as much publicity as I can manage for your sewing.

Keen to be a tester for the pattern? please email me with the following:

- Your name

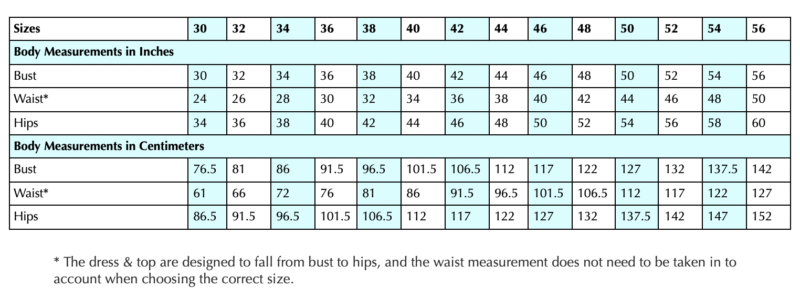

- Your full bust and hip measures

- Your height

- A bit about your sewing experience — particularly knits

- A link to your blog/Instagram/Flickr/Sewing Pattern Review profile/something else sewing-y presence

- A link to a sewing make with a review (so I can see how you think about and analyse your sewing)

- Do you have any other skills that would really make you an extra-super-awesome pattern tester? (i.e. experience copy-editing, cat pictures to bribe me with, 😉 )

- Where are you located (doesn’t need to be too specific – continent, country, state, whatever you’re comfortable with).

If you’ve already applied to/been a tester for Scroop Patterns in the past you are welcome to just copy and paste all the info into a new email, as long as nothing has changed.

Hope to hear from you!

A note:

With all the previous Scroop tester calls I’ve managed to respond to every application personally both when they applied, and once I’d chosen a tester group. Unfortunately due to the volume of applications I’ve been receiving I’m no longer able to do this.

I will only be responding to let people know if I’m able to include them in the testing group or not.