While making the Juno dress, I had a bit of a conundrum with the bodice and train.

There was no way to make my original bodice look just like the inspiration bodice.

So, making a virtue of necessity, I had the idea that I could make a second bodice that fit me perfectly, and looked just like the inspiration bodice. Then I could add additional hooks to make the skirt waist smaller, and the Juno dress would fit a wider variety of models.

But then I encountered a problem. I’ve been studying similar late 1880s gowns for a while, and wondering if the trains actually attached to the bodices rather than the skirts.

Doesn’t the train look as if it might extend from the bodice rather than being part of the skirt?

The theory is sound: it would be much more comfortable to have the weight of the skirt coming from the bodice and hanging off the shoulders rather than hanging from the waist. Additionally, attaching the train to the bodice opens up the possibility of making a second bodice for balls, as trains are a pain to dance in.

Theory, however, needs to be backed up with actual examples of the practice.

So I did some research, and with help from lots of friends, I found these mentions, all from Cecil Willet Cunnington’s English Women’s Clothing in the 19th Century. The emphasis in each quote is mine.

For 1886

Evening gowns: These are frequently without trains, except for mature matrons when the train is fastened round the hips instead of to the back…there is a tendency to use the low bodices for dinner dress. For ball dresses the curiasse bodice…

For 1887

The full evening dress is trained, the train being plain and often gathered to the back of the bodice.

For 1889

Many dresses are made en princesse with ‘V’ backs, laced, the skirts being open in front over an underskirt… The skirt is trained only for full evening dress…

These quotes, while difficult to interpret precisely, seem to imply that the train is usually fastened to the back of the bodice, and that trains were not always used: evidence for fastening my train to the bodice.

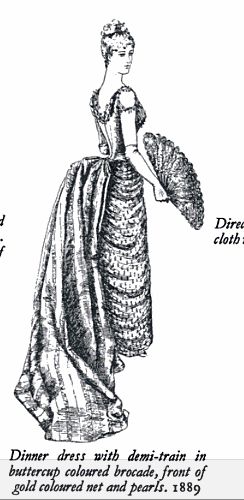

I also found this image (from EWCit19C):

Doesn’t the train really look as if it is attached to the bodice?

And these images, from La Mode Illustree:

The ballgown certainly looks as if the train (well, not a train, but the back skirt part) is attached to the bodice rather than to the skirt.

I can’t quite tell if the entire evening dress is princess cut (in one piece), or if the bodice and train are one, and the skirt is separate.

A couple of quotes and pictures are great, but only a pattern or extent garment would really prove that bodice + train was done for the type of late 1880s evening gown I was aiming for.

Enter the fabulous VandE, who kindly looked through her magazine collection for me and found this picture from Harpers Bazaar, and the pattern that goes with it.

Victory!

Of course, while I had determined that trains could be attached to bodices, and while I know of numerous examples of skirts of the same era that had multiple bodices (this very similar ensemble, for example), I didn’t actually know of any skirts with multiple bodices where one bodice had a train.

To add to this, I realised that if I permanently attached the train to the one bodice, than whenever the other was used the skirt would be train-less, and while still beautiful, not nearly as striking.

So I decided to leave the train as an entirely separate piece than can attach to either bodice.

The only historical Worth examples I know of with completely detachable trains are formal court presentation gowns such as this one from 1886, and this one from 1888, which has three possible bodices, as well as as this one from 1872.

The Juno dress’s train is a bit short for a formal presentation gown, so I’m going to keep looking for other examples of evening dresses with detachable trains in order to support the historical accuracy of what I am doing.

Wow. That is so very interesting. Is the train to be attached with hooks? or is there another way to do it?

I’ve never seen an actual example in person, so I can’t be certain, but I assume the train attaches with hooks. At least that is how I plan to do mine! And I do know that many (most) Victorian skirts attach to the bodice with hooks, so it stays in place.

It does look like the train extend from the bodice in the picture and I have seen prints & ball dresses with the train coming from the bodice.

That’s just my observation.

Your theory does make sense, the bodice + train would be more comfortable and it would take some of the weight off the skirt while moving. From what I seen, I imagine a lady would be exhausted from a night of dancing and carrying the train. Lol.

You can always, God-willing, construct another gown or mock of your theory. And I will most definitely look forward to seeing your work.

P.S: How do you hem a Victorian skirt for walking?

I’m in the process of making one for myself.

The examples I’ve seen have 1 of 3 options:

1: Hemmed just like we do today, sometimes turned 2x, sometimes with the cut edge covered with a band of trim

2: The skirt is cut without a hem allowance, just a seam allowance, and a piece of rougher fabric is sewn along the hem and turned up – it can either be turned all the way, so that the seam is right at the very bottom of the hem, or it can overlap the hem for half an inch on the good outside fabric before turning up and covering the edge to further protect it.

3: Hemmed like we do today, with a pleat or ruffle of another fabric sewn on the inside of the skirt, and extending just the tiniest bit past the hem. This is called a dust ruffle.

Janet Arnold has examples, and good illustrations, of all three.

So happy to have been of help!

I couldn’t have done it without you!

I can’t see any of the pictures except the first one. 🙁

Oh bummer, it’s because they are tiffs. I’ll correct.

I am not good at draping so I tend to use patterns. One company I love is called Truly Victorian. Anyway I found one pattern that does have a “train” attached to the bodice. They call it the waterfall style. Perhaps it will help?

http://trulyvictorian.com/catalog/462.html

Thanks Natalie! I was aware of the pattern, but it isn’t a full train, and it is for daywear, so I didn’t feel it really supported my idea.

Dear Dreamstress,

Perhaps you might check Frances Grimble’s two latest books. At least one includes the period you are going for.

Second, during the First Bustle period, many overskirts were attached to a belt. Wondering if this method may have carried over to the second bustle era.

Finally, the train-crazy natural form era just preceding the 1880s is covered in another Grimble book. With the short span of years separating the two, it’s likely that methods used then would carry over, and I have that book. Will check for you.

Best,

Natalie in KY

Thanks! Grimble’s books are on my Christmas wish list!