My last two terminology posts were so popular that I’ve decided to make them a regular feature, so you can now look forward to them every Thursday or Friday.

I even got all excited and (maybe just a bit overly ambitious) and started a grandly titled Great Historical Fashion and Textile Glossary, so that you can see them all in one place (including anything I’ve written in the past that defines and describes a historical costume and textile term nicely). As it develops I’ll do fancy things like allowing you to skip to the letter you want and all that.

The last two terminology posts I did were about 19th century fashion, and I’ve done a lot of fabric terms in the past, so thought it was high time I posted an 18th century definition. So I started researching the sabot sleeve, a term I am familiar with from 18thc fashion plates (but as it turns out, was probably mistaken as to what it meant), and as I did I found the term was also used in the 19th century – so so much for staying 18th century!

When I started this research I thought that sabot sleeve referred to the the ruffled lace trimmed sleeves usually seen with 18th century robe de coer, such as the ones seen in this portrait in Marie Antoinette:

And this portrait:

I think my confusion over the first type of sleeves may stem from this fashion print. You can see that the sleeves look a little bit like the lace sleeves on court robes.

The problem with knowing if those really are sabot sleeves or not is my poor grasp of French. I’d translate the description as roughly:

A Circassienne dress in the new style, of gauze in a sulphur colour, with trim in lilac gauze. The flounce trim is in the same colour as the dress, as is the bottom of the sabot. The whole thing trimmed in lilac and purple, even to the headdress.

Unfortunately, I don’t know if they mean sabots for sleeves, or sabots for shoes, or for something entirely different! If it is the sleeves, you can see how they look like the lace sleeves worn with court dress. It also explains the 19th century usage of sabot. (obviously if you are good at translating 18th century French & can tell what the description is meant to mean please speak up!)

For a completely different take on sabot sleeves, I’ve seen late 17th century and early 18th century sleeves with wide turned back cuffs referred to as sabot sleeves:

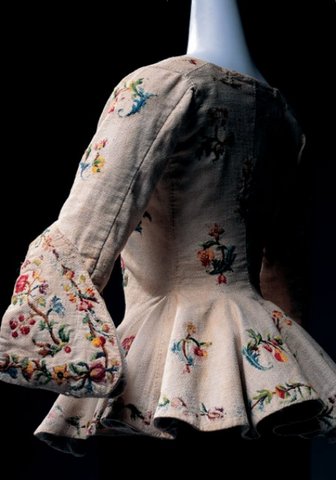

17th century casaquin of Italian origin at the Kyoto Costume Institute. Described as cotton/linen with wool embroidery, sabot sleeves

I can’t find any period sources for calling the above type sabot sleeves, despite a few museums doing it.

For yet another variant of a definition for sabot sleeves, we can look at modern glossaries of 18th century dress, which definite sabot sleeves as a narrow sleeve with a curve at the elbow which was popular in the later half of the 18th century. The name apparently comes from the way the sleeves fit over the elbow like a clog – the sabot shoe.

The Marquis de Paulmy, in his “Precis de la Vie privee des Français” (1779), describes the shoes

“Stout leather shoes are looked upon as a luxury by the poorer classes, who think themselves fortunate when they have shoes with thick soles. In some parts of the country, the peasants wear nothing but sandals, clogs, or pieces of rope wound round the feet, and in others men and women alike wear the sabot” (wooden shoe)

Here are a couple garments with this type of sabot sleeves:

The ruched cuff seems to be so closely tied to this type of sleeve that it is called a sabot cuff. The Kyoto Costume Institute, for example, frequently uses this term.

And then there is a Galerie des Modes fashion plate with yet another usage.

This fetching yellow frock is describes as:

…caraco of taffeta trimmed en pouf has short sleeves ending in manchettes to which sabot sleeves are attached. “

So there you go. Half a dozen different possibilities for exactly what an 18th century sabot sleeve is! The truth probably is that the definition changed from decade to decade, and wasn’t every clearly defined.

Whatever it exactly was in the 18th century, the sabot sleeve fell out of favor for the Regency period. The term saw a resurgence from 1820, when it referred to a sleeve with one or two puffs above the elbow, or to the puffs themselves. This style was seen on evening dress from 1820 to 1836, and on daywear from then until 1840, when it fell out of fashion. The term was used almost synonymously with bouffant sleeves.

The Court Magazine describes evening fashions for 1836:

Evening dress robes continue to be cut very low round the bosom, and the majority made with short sleeves. These are now, for the most part, made close to the arm, but with two or three sabots of the same material or else of white tulle, the latter is most fashionable, and certainly it has a very light and pretty effect upon a robe of rich silk or velvet. We see also some sleeves with the first beuffant composed of the material of the dress, and the second in blond ortulle, terminated by a manchette.

This week’s Rate the Dress, whatever you think of it otherwise, is the perfect example of an evening dress with sabot sleeves:

Hmmm…the style certainly looks more like the Circassienne than like the ruched cuffs!

In The Dictionary of Fashion History by Valerie Cumming, C.W. Cunnington and P.E. Cunnington they define Sabot Sleeve as: A variation of the bouffant; a single or double puffed-out extension above the elbow, worn with evening dress from 1827-1836 and for day wear from 1836-1840, then becoming the Victoria sleeve.

The times don’t fit well, but that covers those lace sleeves nicely!

That’s one of the sources that I used for the 19th century terms, but unfortunately they don’t discuss its 18th century use at all!

What all of these sleeves seem to have in common is that they puff in then out, rather than open out like a pagoda. Sometimes this refers to a ruched strip laid over it, or lace laid over it. Engageates of lace opened in a fall, thesabot lace sleeves don’t. Could that be the defining feature?

Interestign! Sabot means “hoof” which is where the term got linked to a clog. So the earliest cuffed sleeve examples are probably the most realest, because don’t they just look like a hoof at the bottom oa a leg!

Peasants wearing wooden shoes (as they often did in France) would have sounded just like horses, too. Cool link.

Thanks! I’d always wondered exactly what sabot sleeves were.

So interesting!

But the circassienne fashion plate made me even more confused… I always thought a circassienne was a gown with a very short sleeve over a longer sleeve. Or that is what I’ve heard others called it, and I just went with it!

Keep it coming! It’s awesome!

Doing this research is really making me realise how many terms I use because that’s what I have heard others call them, when that really isn’t what they meant historically at all.

Beautiful.

I WANT a jacket cut like the embroidered 17th century casaquin. That’s SOME peplum, and the sleeves are to die for…

Interesting post.. It’s like a sabot is the bit of the sleeve that allows freedom of movement… All that ruching would have a lot of give, and the other parts of the sleeve could be quite tight. Maybe that’s “sabot”? Like a point on the garment that isn’t tightly fitted but still decorative and mobile?

Just a thought…

The ruching is an applied decoration over a solid sleeve, so I don’t think it would give much more movement. It’s a fascinating theory though!

These posts are really very interesting!

Thank you 🙂 That means a lot coming from you!

Interesting seeing a ‘sabot’ I dance wearing clogs, but they have leather and wood in construction. And unexpectedly comfy as well.

My focus is on 1600-1730s fashion. The Italian jacket is a casaquin as stated which is a short casaque. (Not to be confused with the Cassok.) You can tell because the bodice extends into the peplum as one piece. Plus the sleeves are typical. By the 1700 the sleeve of the casaque changes significantly and became what you see in this jacket. A trumpet like sleeve, in this case, are turned back. These sleeves are like this because they are used for riding horses, which is the original use of the casaque since it was imported from the east. It is also the foreboder of the English riding jacket. These jackets are design to allow for movement in the shoulders, elbows, wrist and obviously at the waist..hence the flared out peplum. It was probably worn over a vest. French reference do not go back far enough. You have to use Italian ones. Italy began trade in the middle ages which is where a number of garments originated that are still found in the 17th and 18th century. For the record, I sometimes see jackets with pleated or saque backs called casaquin…this happens with 18th century authors trying to describe a variety of jackets. But casaques and casaquin have a specific cut that is still found in some folk costumes today. Great blog by the way…Love the range of topics and your sewing ! Great work