Up until the mid-19th century, almost all dyes were made from materials found in plants (indigo, woad, woad, madder, brazilwood, tumeric and others), animals (shellfish purple, cochineal), and minerals. While these dyes could produce an amazing range of colours, there were still some colours that couldn’t be produced by natural means, and some of the colours that could be produced by natural means were inclined to run, fade, or to destroy the very fabrics they dyed.

Then, in 1856 William Henry Perkin, a young chemistry student, working at home, after hours, in a makeshift laboratory, trying to create a chemically identical artificial version of quinine (a very valuable plant-based drug which was used to treat malaria), thought to experiment with the results of another failed attempt.

The result of his experiment on his experiment was mauveine (also known as Perkin’s mauve, aniline purple, harmaline,Tyrian purple, plain old mauve, and, if you want to be extremely technical, 3-amino-2, ±9-dimethyl-5-phenyl-7-(p-tolylamino)phenazinium acetate). Mauveine was a combination of aniline (a common extract of coal tar) and other compounds which created a brilliant purple which was the first mass produced chemical dye.* Mauveine would lead the way to dyes in dozens of other shades, all made from aniline from coal tar, and to everything from the modern dyes we use today, to cancer treatments.

Perkin called it first Tyrian purple, after the shellfish-based purple worn by Roman emperors, and then, when it was pointed out that this name was confusing (referring, as it did, to a real animal based dye), mauve, after the mallow flower. In scientific papers he referred to it as mauveine. I’ve chosen to use this last name, as it avoids confusion between mauve (Perkin’s colour) and mauve (the generic pinky lilac colour).

That’s the basic story of how aniline dyes were invented, but the backstory behind it, and the story of how Perkins’ initial experiment in the attic of his father’s house made him a rich man, are just as interesting.

To start with, the fact that Perkin was studying chemistry was pretty amazing in and of itself. Chemistry was in its very infancy as a science, and most of the rest of the scientific and industrial world thought that chemistry, at best, produced a few neat party tricks but had little practical applications, and that at worst, it was just a new form of alchemy. It is only because the English royal family had such strong ties with Germany, which had a chemistry community, that there was a school of chemistry at all in England for Perkin to study at, and a brilliant German chemist for him to study under.

Perkin’s discovery wasn’t actually unique: other chemists, and even Perkin himself, had noticed that extracts of coal tar could create colours. As early as 1826 chemists had noticed that aniline was a component of plant based indigo dye. By 1840 they knew it was also a by-product of coal tar, and that it could produce colours. In Feb 1856 Perkin had even submitted a report on a bright crimson colour that was the result of an experiment with hydrogen and benzol (which is a byproduct of coal tar). So Perkin’s great achievement is not that he found a colour out of aniline or another coal by-product, but that he pursued its possibilities.

Not only did Perkin pursue the possibilities of his discovery, but he did so in the face of great disapproval. His father had not wanted him to become a chemist in the first place, and Hoffman, his brilliant German mentor, was not brilliant enough to realise that a chemist could be both a scientist and a businessman, and that practical chemistry need not detract from pure chemistry. Hoffman called Perkin’s discovery ‘Purple sludge’ and told him that if he pursued industry, he would never be able to return to chemistry.

In order to make his colour into a dye, and his dye into a business, Perkin had to convince his father to bankroll what seemed a mad enterprise (too mad for any bank to agree to fund it) and leave his mentor, and (he thought) and chance of a proper scientific career behind. Perkin risked everything, and he got his family to risk everything, for his idea.

The idea was pretty mad: Perkin knew that his solution dyed fabric a brilliant purple, but he knew nothing of the dye industry, nothing of fashion, and little of business. To make matters worse, his initial mauve dye would not dye cotton: only silk and wool, and cotton was a hugely popular fabric in late 1850s. Plus, extracted aniline was prohibitively expensive, making the production of the dye unprofitable.

Amazingly, Perkin persevered. After much experimentation he found that tannin (the stuff that makes tea taste bitter if you let it sit too long) worked as a mordant which attached mauveine to cotton. He figured out a way to extract aniline less expensively. He also found a dyer to work with, found a spot for a factory, and built his own factory to produce mauveine dye. That’s right – rather than discovering the dye and then immediately rolling in the riches, Perkins had to build his own factory to produce it, and find industry dyers to buy it.

Luckily for Perkin, his timing was perfect. Just as he launched his first dyes, the French Empress Eugenie, the most fashionable woman in Europe, and certainly the most imitated in terms of dress, decided that lilacs, purples and mauves matched her eyes perfectly. Probably on her advice Queen Victoria wore, to the wedding of her daughter the Princess Royal in 1858, a dress of “rich mauve velvet, trimmed with three rows of lace…the petticoat, mauve and silver moire antique”. The mauve of Queen Victoria’s dress was more lilac than brilliant purple, and was almost certainly the product of natural dyes made from lichen, but the result was the same: all shades of purple were in.

Dress, 1862-1864, Musee McCord, M965.112.1.1-2. This dress could have been dyed with either natural dyes or aniline dyes – or both.

By 1859 an English newspaper wrote that Mr Perkin “can itinerate Regent Street and perambulate the Parks, seeing the colours of thy heart waving on ever fair head and fluttering round every cheek.” The satire paper Punch, predictably, was less flattering and described London as being struck by an epidemic of mauve measles, a serious illness which began with “a rash of ribbons” and progressed to cover the whole body in mauve. According to Punch women were particularly susceptible to the disease, but ‘a single dose of ridicule’ was usually enough to cure a man.

The popularity of mauve and mauveine dye was boosted by the fashion for the crinoline at its widest, and the increased lengths of fabric that took, not to mention the need for pretty stockings and petticoats that were often exposed by gusts of wind and unfortunate seating.

Fashion plate featuring a girls dress in mauveine, a ladies bonnet with magenta ribbons, and a walking dress in aniline green, English Woman’s Domestic Magazine, June 1864

Mauve, as exciting as it was, could not be the cutting edge of fashion forever, and in 1861 it was falling out of style, to be replaced by 1859’s Verguin’s fuchsine (a rich crimson red, also known as solferino and magenta), and in the 1860s, Bismark brown, Hofmann’s violet (a different vivid purple, and yes, its named after the Hofmann who derided ‘Purple sludge’), Magdala red, Manchester brown, Martius yellow, Nicholson’s blue (a vivid teal blue), aniline yellow, bleu de Lyon, bleu de Paris, and aldehyde green.

To compete, Perkin came up with another flower-themed shade: dahlia, a colour between mauvine & magenta; the patriotic Britannia violet (appropriate as he was having to compete with numerous continental dye companies), which was a deep blue; Perkin’s green; an aniline black; and the rich purple seen in the frock below.

Day dress, Great Britain, United Kingdom, France, 1873, Silk and ruching, Victoria & Albert Museum T.51&A-1922

While the best known and most obvious aniline shades are extremely bright and vivid, not all aniline dyes are extremely bright. Customers enjoyed the novelty of bright shades which had never been previously possible, but aniline dyes were also valued for their washability and lightfastness. Dyers such as Perkin went to great lengths to prove that their dyes were more durable and washable than natural dyes, and that the only aniline dyes that faded, stained and came out in the was were those that were prepared and dyed improperly. Part of what made aniline dyes so successful is that they had attributes that made them valuable beyond their initial aesthetic: they were easier to source, cheaper, and often worked better than their natural alternatives. From the very early years of aniline dyes, muted, subdued aniline shades were made and sold, but it is much more difficult to identify garments made from aniline dyes in shades that could also be made from natural dyes.

All the new aniline dyes became more and more popular, the market for natural dyes collapsed. Cochineal dropped in price from 15 cents per kilo in 1858 to 8 francs in 1862, safflower from 45 to 25 cents per kilo. The madder industry was wiped out forever. Even when the fad for the brightest, most vivid, early shades disappeared, the old natural colours were replaced by synthetic variants. Aniline dyes were here to stay.

This dress may have been dyed with ‘dahlia’ or a similar shade, or even a natural dye. Paris, France, 1869-1870, Vignon, Ribbed silk trimmed with satin, faced with cotton, brass, Victoria & Albert Museum, T.118 to D-1979

And what of Perkin? I’m happy to report that he reaped the benefits of his discovery, his daring, and his perseverance. His business prospered, he became comfortably wealthy, respected as a businessman and a chemist. He continued to make important scientific discoveries throughout his life Tragically, he lost his first wife to TB, but he had a happy second marriage, and his children went into the family industry. Ironically, it was the scoffing Hofmann who initially was given (and happily took) the credit for the discovery of aniline dyes, but Perkins preferred research, work and family life to an endless round of speaking and adulation. As the 19th century passed his public profile rose and rose, until the 50th anniversary of his discovery was commemorated with dinners and medals across the globe.

* Contrary to popular belief, mauveine wasn’t the first chemical dye. In 1771 indigo was combined with nitric acid to dye silk a bright yellow, and both red aurin made from carbolic acid and deep blue pittacal made from beechwood tar were discovered in 1834. The difference is that none of these was produced in any notable quantity, nor did they inspire chemists and dyers to pursue other chemical based dyes.

For more examples of aniline dyes, see my pinterest page.

Sources:

Finlay, Victoria. Colour: Travels through the Paintbox. London: Hodder and Stoughton. 2002

Garfield, Simon. Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour that Changed the World. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 2000

Fascinating! This is really interesting – I had no idea. Despite having a high school chemistry teacher who was a passionate natural dyer, I never thought to wonder about the origin of chemical dyes.

Beautiful strong colours. Really interesting article, thank you.

Never before, and probably never again, has an entry on your blog made me go, “Agh, my eyes!” I do wonder if recent advances in dye tech are behind the craze for neon colored clothing?

Clever woman! They are indeed! But not as much as the first craze for neon clothes in the 80s, which really was triggered by completely new technology.

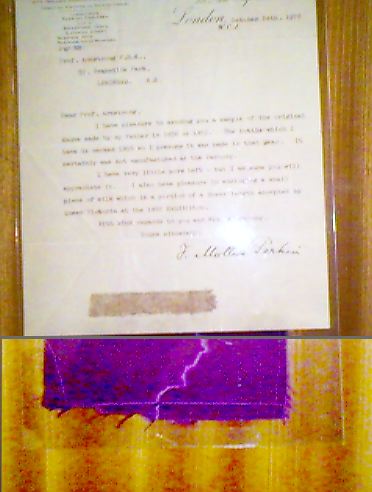

I really enjoyed that book “Mauve” and recommend it heartily to your readers. I thought his name was Perkin though (no S – letter from his son that you picture is signed Perkin). I also love mauve the color. Way to start a fashion trend huh?

Loved this, as usual. And, yes, some of those early versions approach neon. WOW.

I was reminded of the scene from Louisa May Alcott’s “Rose in Bloom” when Rose admires, caresses and eventually does not purchase a bolt of lavender or violet silk. (She decides it would self indulgent since her white ball gown will more than do.)

This is off topic for this post — but your comment about the fringe on the 20’s frock was fresh when on p. 2 of the Sept. 8, 2013 NYT Style section advertised a frock w/just such a fringe! Very cool.

Or in “Little Women”, when Meg spends $50 on 25 yards of violet silk!

I love posts on dyes!

That 1873 blueish-purple dress is such a lovely color, too!

I was thinking of Courtney Milan’s The Heiress Effect, where Jane wears a fuchsine dress.

“What does one call a color like that?”

She smiled at him. “Fuchsine.”

“It even sounds like a filthy word,” Oliver replied. “Tell me, what sort of devilry is fuchsine?”

” It’s a dye. A new one, a synthetic one, made from some kind of coal tar, I believe. Some brilliant chemist with a talent for experimentation and no sense of propriety came up with this.”

“It’s…” There were still no words for it. “It’s malevolent,” he managed. “Truly.”

Thank you for the detailed explanation! I have always loved those bright colors on Victorian fashions, and now I know a bit more about where they came from!

Oh I love this! I find this period of history, and these dyes in particular, so fascinating. Can you talk a bit about colourfastness? I have read that a lot of the early aniline dyes weren’t colourfast over time, so a lot of extant clothing looks brown or else faded versions of the colours they once were. Which is why steampunk clothes are so dreary, rather than being vivid purple! Is that right, or have I got the kind of dye wrong?

A really wonderful post, as interesting and entertaining as it was informative! I knew a little about aniline dyes, but not much. Thanks so much for the enjoyable lesson!

This is my favorite informational post so far! Wonderful–so interesting, too!

This is fascinating! Good for Perkin for putting so much work into creating a business out of his purple sludge!

I love purple, but these are WAY too loud, except the closeup of the blue-purple bustle from the V&A.

Is Punch saying that men occasionally wore this colour too? I have never seen such a colour on any 19th century men’s clothes. Perhaps the “dose of ridicule” came so swiftly that there was no time to immortalize it in a fashion plate.

I love when you do these interesting history posts.

I guess the alchemists did have the right idea about turning base materials into gold, they were just focusing their attention in the wrong place. Instead of lead, they should have been trying coal tar.

That purple reception gown with the fabulous folded train is now on display at the Civil War and Victorian Dress Collection museum in Fort Worth. They also have the brown voided-velvet dress from the Tasha Tudor collection as well.

I’ve that Simon Garfield book you referenced in my wishlist – a lot of mixed reviews, though. Worth it?

I had very mixed feelings about that book. It’s the most comprehensive book on Perkin available, but it didn’t answer a lot of the questions I had. It was also very bitsy and uneven in tone, and didn’t explore and consider some of the claims it made in a way that a good researcher should. I’d borrow it and read it before committing shelf space to it.

I read about Perkin and mauveine a long, long time ago in a Czech book about colours (from all kinds of viewpoints) my mother’s got. It was a very, VERY fascinating book that I loved to read as a child (or, most of the time, just look at the pictures), and then re-read later on. But you included more details I did not know about, like the other dyes etc. etc., so thank you very much!

It’s particularly interesting about cotton, and the not-so-bright colours, and the way colours came and went into and out of fashion.

Just starting to develop a ‘Working the Chemistry’ strand on my blog to look at dyeing pre-Perkin and how Henry Wm Ripley and those under him managed to dye mixed worsted’ ‘in the piece’ at Bowling Dyeworks in the late 1830s. Loved your post, Loved the Pinterest page.

I just stumbled into the fascinating story of William Perkin and the “invention” of mauve a few days ago, but I’ve read a lot about mauve since then. I have to say this piece is – by far – the best thing I’ve read on the subject: Solid, illuminating research that dispels a lot of the myth and misapprehension (and simplification) that exists elsewhere, written and presented in a wonderful, accessible and immensely relevant style. Thank you so much for sharing your knowledge and enthusiasm. If I write anything about Perkin and mauve, I will be sure to point people in the direction of this piece for greater insight and I will, of course, be sure to give big props to you in my piece, since I can’t see how I could possibly avoid quoting you after reading this delightful and immensely informative post.

Thank you for this article. I am currently researching for a book on US Civil War era crochet and using contemporary texts I am seeing patterns made in in multitudes of color, some which would look very much overdone to modern eyes. I knew that aniline dyes were developed in the mid-19th century, so I wondered if there was a connection. Your article assured me of the truth of that! The white Victorian houses and sometimes drab clothing attributed to that era are wrong—the “Painted Lady” houses of San Francisco are much closer to the truth.