The theme for the Historical Sew Monthly 2015 Challenge #2 is Blue: make something in any shade of blue.

I knew it would be a popular colour challenge choice because blue is simply the most popular colour: it’s more peoples favourite colour than any other.

Historically, it’s also been one of the most desirable colours in many historical periods and cultures, because the dyes used to achieve it were comparatively expensive and finicky, and the harder something is to achieved, the more expensive it is, and the more people want it.

In addition to being an expensive dye, blue acquired even more cachet in Europe in the Middle Ages when it became the colour associated with the robes of the Virgin Mary in devotional art. Mary was painted in blue robes partly because blue was the colour of the heavens, but mostly because the most expensive paint available was ultramarine blue. Mary was deemed worthy of only this rarest hue, this colour ‘from beyond the seas’, so was depicted in blue robes, often highlighted with the only colour more valuable than ultramarine blue: pure gold.

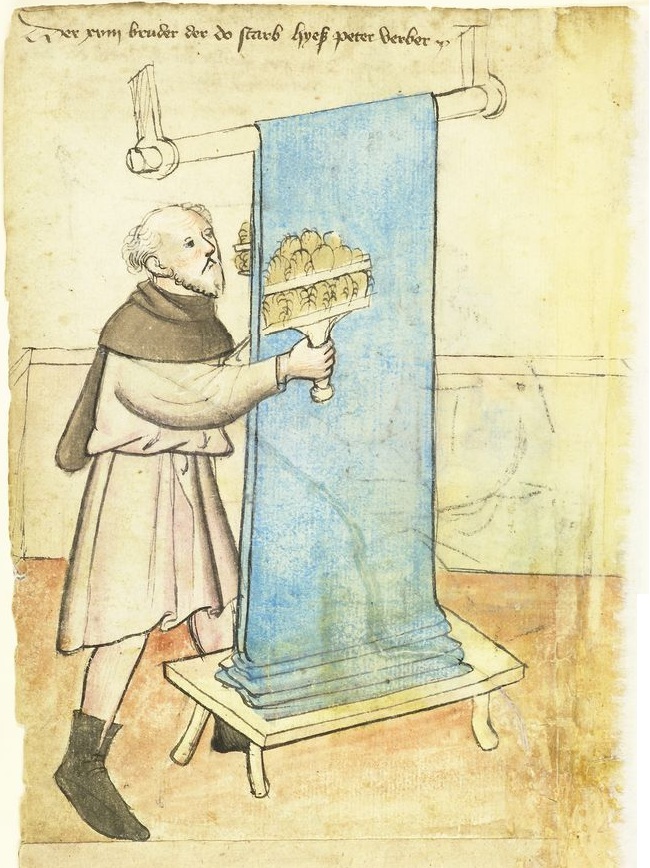

Mary’s robes probably wasn’t meant to correspond to a specific existing fabric dye colour, but a range of beautiful blues were achieved in Europe from at least the Iron Age, and throughout the Middle Ages with the plant dye woad (Isatis tinctoria).

Woad was one of the cornerstones of the Medieval and Renaissance dye industries, and whole towns grew, and grew rich, around growing and processing woad.

Mary Magdalene from the Braque Family Triptych (right panel), ca. 1450, by Rogier van der Weyden (early Flemish, 1399:1400-1464)

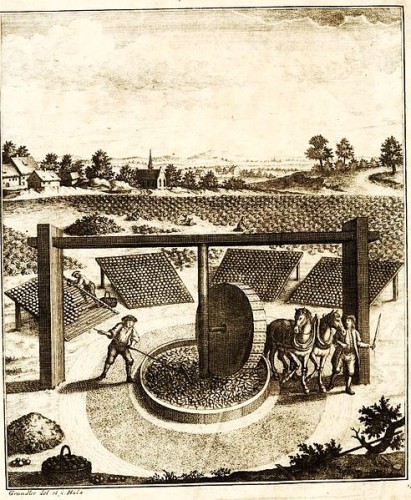

Illustration of German woad mill in Thuringia from Daniel Gottfried Schreber’s book on woad. 1752

The problem with woad as a dye was that it takes a great deal of woad to dye a small amount of fabric – and the richer the blue that was desired, the more woad that was needed. So when European traders established sea trade routes to India in the 15th century and discovered Indian textiles dyed with the ‘true’ indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria), which has the identical dyeing chemical (indigotin) as woad but at a much higher concentration, and so thus dyed the same range of blues, but with less plant needed to achieve them, they thought their fortunes were made.

Indigo was a novelty to European traders in the 15th century, but it wasn’t the first time it had reached Europe. The Romans had dyed fabric with indigo imported from India, but the decline of the Silk Road trade had made it a rarity in ensuing centuries.

As traders began bringing indigo dye back to Europe in the 15th centuries, governments realised the devastating effect it would have on their local dye industries, and took steps to discourage people from buying indigo dyed products, or dyeing with it. Indigo dye was dubbed ‘the devils dye’. Official edicts were issued warned that the dye was corrosive and would rot fabric. When warnings weren’t enough, stronger steps were taken. In 1577 indigo dye was officially prohibited in parts of what is now Germany. France, in 1609 called it “the false and pernicious Indian drug”, and forbade its use.

Despite the prohibitions, there was no stopping progress. It was impossible to tell if a fabric had been dyed in indigo or woad once it was dyed, so indigo dyed fabric, or fabric dyed with a mix of the two dyes, became more and more common across Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially as more cotton fabrics, which required more dye than wool to colour, were imported from India.

In the 1750s the usefulness of indigo dye combined with the novelty of cotton fabrics and a newly developed technology: engraved copperplate printing, developed in Ireland in 1752, to create a classic textile look: the blue engraved-printed on white design. Known as ‘China Blue’, for it’s resemblance to blue and white porcelain, the resulting fabric was known for lighter blues on light grounds, as the process could not produce dark blues. The most notably example of the look is the fabric known as ‘toile de jouy’ look, after the town in France that produced the fabric with little pastoral scenes scattered across the fabric (though this fabric was rarely used for garments, with vining florals being much more common).

Gown, blue floral pattern on cream ground. 1760-1790, Copperplate printed linen. Worn by Deborah Sampson, possibly as her wedding dress. Historic New England, 1998.5875

Engraved printing, unlike the earlier woodblock printing, could produce fine, detailed designs, but only in one colour. Indigo blue was one of the most durable available dyes suitable for engraved printing, and combined with bleach innovations which kept the fabric very white, made blue and white combinations one of the most popular.

Indigo production had its dark side: when England took over India indigo was such a desired commodity that huge plantations were established to grow it. The native workers on the plantations were essentially slaves, and British indigo plantation owners had appaulling track records. The terrible conditions led to the 1859 ‘Indigo Revolt’ as workers attempted to better their conditions, but without much effect. In 1860 a native writer commented

“We have nearly abandoned all the ploughs; still we have to cultivate indigo. We have no change in a dispute with the Sahibs. They bind us and beat us, it is for us to suffer.”

There were also indigo slave plantations in the Americas in the 18th century.

Despite the revolts and the growing movement against slavery in the West, the popularity of indigo as a dye kept cultivation high. In 1897 it is estimated there were at least 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) of indican-producing plants (mainly true indigo) under cultivation. Most of these acres were in in India, and most of them were cultivated under horrific conditions.

What revolts and human rights campaigns couldn’t change, innovation could wipe out in a few short years. The discovery of aniline dyes in the late 1850s opened up the possibility of a cheaper chemical alternative to natural indigo. The first aniline dye was purple, but in the 1860s Nicholson’s blue (a vivid teal blue), bleu de Lyon, bleu de Paris, Britannia violet (a deep blue) and other bright shades of aniline blue were produced.

Child’s cape. Twilled peacock blue woollen cloth, embroidered in cream silk thread, with a cream tassel on the hood; Anglo-Indian, 1860-70, V&A

However, none of these were comparable to indigotin in the range of shades they could produce. Every chemist working with aniline dyes attempted to synthesize a synthetic indigo dye, but it wasn’t until 1897 that a commercially viable process was developed. This process, however, was so successful that it almost wiped out the natural indigo industry.

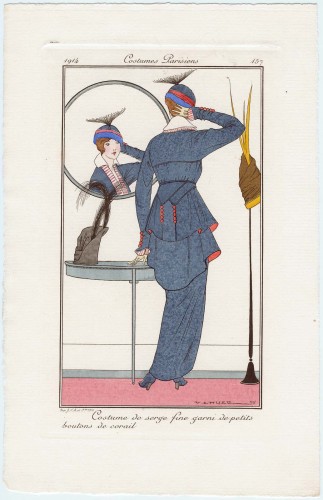

Costume de serge fine garni de petits boutons de corail, plate 157 from Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1914

By WWI almost all blue dyed fabrics were produced with synthetic dyes, though there was a very slight resurgence in natural dyes in both WWI and WWII, as the chemicals used in synthetic dyes were required for the war effort.

For more blue inspiration for the Blue challenge, check out my Blue pinterest board (which works its way from the present to the past as you scroll down the board. I’m only up to the mid-18th century as of the writing of this post, but there should be more recent stuff soon)

Sources:

Balfour-Paul, Jenny (2006). Indigo. London: Archetype Publications. ISBN 978-1-904982-15-9

Finlay, Victoria. Colour: Travels through the Paintbox. London: Hodder and Stoughton. 2002

Garfield, Simon. Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour that Changed the World. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 2000

I always look forward to the research posts that you write! But this one in particular I liked, as it ties in neatly with my political anthro class! We were discussing rebellions and revolts, and the class unanimously decided that all rebellions are successful. I’ve already jotted down a few notes about the indigo revolts, for next class. Thank you for taking the time to write such a wonderful post!!!

Thank you! I’m really glad it was useful and enjoyable!

I guess the answer depends on what you call a rebellion or revolt, and what you call a civil war. The US Civil War could be considered a massive unsuccessful rebellion. There were numerous small unsuccessful ‘rebellions’ in NZ in the 19th century (if you can call it a rebellion if the locals are simply trying to retain rights to their own land), such as Te Kooti’s War. The Sioux Wars, and a number of other 19th c conflicts between Native Americans and whites could be called rebellions in the same sense as Te Kooti’s War or the Indigo Revolts. The Bougainville Conflict is a more recent unsuccessful rebellion. (Hmmm…I think my original International Relations degree is beginning to show 😉 )

Was that meant as a terminology distinction?

Because if your class thinks that rebellions/revolts, without a distinction, are always successful, that’s definitely nonsense… Czech history is littered with unsuccessful uprisings. 😛 (Saying that because I’m Czech. All history is littered with them.)

Fascinating!

Terrifically interesting -thank you, you’ve taught me something I had no idea about. We seem to know so much about the history of the murex snail that produces purple, yet the history of the indigo is far more obscure. Isn’t indigo dye intimately tied to the creation of the blue jeans, the single most ubiquitous cultural icon of the modern era?

Speaking of indigo, it that what turns my hands and fingernails blue when I work with denim, or is that a chemical dye these days?

Almost all modern denim is dyed with synthetic (chemical) indigo, rather than natural indigo, but synthetic indigo will stain your hands as well. I know of just two companies making natural dyed indigo – and they are both doing it on organic cotton, for specific manufacturers.

I wonder if the traditional Czech manufacturers of modrotisk use natural or synthetic… they only mention “indigo dye”, but not in a way that would make it clear…

I really enjoyed this post! I’ve always found both woad and indigo dyes fascinating, not least since I read (only read, as yet – mum and I are trying to convince woad plants to grow where we live) that the dyeing process involves a kind of oxidation process, where the fabric turns blue when in contact with air, not before. I always imagine that it must have seemed like magic the first time someone tried it: dipping fabric and then watching the blue appear when the fabric is lifted into the air.

My chosen time-frame does not really seem a “blue period”, but am going to make a blue-ish dress anyway. Because it IS pretty.

It’s a fascinating history – I was especially intrigued by the prohibition of indigo!

I mention modrotisk above – that’s a resist dye technique / fabric that gained popularity in the Czech lands in the 18th century, using woodblock printing. As I’m reading about the Moravian Wallachian folk costume (for which it is quite typical), I’m learning the traditional style, as used on the aprons, involves small-scale, widely spaced floral patterns, with a densely printed border.

There’s also a fascinating mention of tentative and unproven, but still fascinating :-), possible connection between blue embroidery on shirts and evangelical/Protestant/whatever-else-you-call-it-in-English villages in the area… I’m saving this mostly for the Heritage challenge, because I already have other blue UFOs I need to finish in February; but it tickles me that my favourite colour is so closely linked to part of my heritage!

how wonderful!

While I didn’t research the prevalence of the colour blue before picking blue linen to work with my chosen needed costume piece, this history is really interesting…

I made an underdress for my Norse Viking Age wardrobe which is quickly growing!

https://dawnsdressdiary.wordpress.com/2015/02/02/blue-linen-underdress/

A nice irony that one thing we moderns regard as bad: artificial dye rather than natural, prevented another: exploitation of slave workers.

Indeed. Though today the chemicals in the artificial dyes are ruining the environment in China, and causing terrible health problems for the workers who work in them – often under near-slavery conditions. :-/

[…] de mon corset pique. Dans les semaines qui viennent je vais me mettre au challenge Blue du Historical Sew Monthly (une jupe 1830 à carreaux bleus), je vais coudre la robe de soiree d’Elsa (en pièces […]

[WORDPRESS HASHCASH] The comment’s server IP (192.0.82.170) doesn’t match the comment’s URL host IP (192.0.78.13) and so is spam.

[…] The Challenge: Blue […]

[WORDPRESS HASHCASH] The comment’s server IP (192.0.101.46) doesn’t match the comment’s URL host IP (192.0.78.12) and so is spam.

I made a blue sontag, or shawl. Blog post here: https://costumegirl.wordpress.com/2015/02/16/a-sontag-or-a-historical-shawl/

ctokmuseum.orgctokmuseum.orgSince I am knee deep in museum affairs at the moment- this month’s blog post about my blue Edwardian working dress is at the museum’s blog where I “guest post” http://www.ctokmuseum.org/along-the-trail/in-the-footsteps-of-my-foremothers

WOO HOO- project #2 blue done 1920 baseball cap http://wickedstepmother.weebly.com/wickeds-compendium/play-ball-recreating-1910-20-baseball-uniforms

I stitched an 18th century needlecase, which features a blue flower in the center of each petal.

http://teacupsinthegarden.blogspot.com/2015/02/18th-century-cross-stitched-needlecase.html

I’m also hoping to whip out 18th century wedding pockets, that are embroidered blue.

Laurie

I love your research posts they are really informative. I made an early 30s beach ensemble in a crazy deco print. https://romancingthesewn.wordpress.com/2015/02/23/historical-sew-monthly-challenge-2-blue-1930s-beach-ensemble/

I made a business card wallet and an apron.

Posts:

https://americanseamstress.wordpress.com/2015/02/09/hsm-2015-2-business-card-wallet/

https://americanseamstress.wordpress.com/2015/02/20/hsm-2015-2-apron/

It is such an interesting part of history! I didn’t know how much this blue was prized in the past!

I became interested in indigo dying when i met a traditional “noren” (japanese front door drapery) maker using real indigo dye in his workshop deep in the jungle in Okinawa, Japan. Since i am allergic to a dark chemical dye named paraphenylendiamine (PPD), my interest just grew stronger about indigo. For now, i will just satisfy my blue craving by underglazing my porcelain with blue cobalt… But your post give me a lot of inspiration for future sewing projects!

reenactorix.comreenactorix.comThank you so much for these research posts. They’re awesome! This month, I made an 18th Century petticoat out of gorgeous blue linen!

http://www.reenactorix.com/2015/02/historical-sew-monthly-challenge-2-blue_26.html

nigdziekolwiek.comnigdziekolwiek.comI’m not very into sewing this month, but trims and belts are parts of costume too, right?

So I weaved them both http://www.nigdziekolwiek.com/en/mniej-niz-wiecej-mammen-hsm15-wyzwanie-2/

Blue is such a lovely colour, I’ve enjoyed this month’s challenge!

I’ve made a Kimono-esque dressing gown:

http://ohhatface.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/historical-sew-monthly.html

I made a World War I VAD uniform: http://misshendrie.blogspot.nl/2015/02/world-war-i-vad-uniform.html.

Here is my 17th century skirt, http://thecostumingdamsel.blogspot.com.au/2015/02/hsm15-blue-challenge-complete.html

A two piece ensemble from the 1920s: https://aboutmybuttonbox.wordpress.com/2015/02/27/hsm-2-colour-challenge-blue-sunday-best/

Here is my 1880’s Natural Form Gown:

http://aimeevictorianarmoire.com/2015/02/07/hsm-color-challenge-blue/

Done, I have finished my 2nd challenge. 1803 Regency dress from a watercolor print found at LACMA. It was a lot of fun.

https://sewingfromanothertime.wordpress.com/

I love the peacock blue children’s cape from the late 19th century, thank you for the very inspiring research!

For my Blue challenge, I made a late 18th century men’s waistcoat for my husband: it’s a bit different & new, sewing for a man’s body versus a woman’s fitted with stays/corset is new, but a good challenge!

http://theladydetalle.blogspot.com/2015/02/february-hsm-challenge-colour-challenge.html

I made several blue items this month, (all begun previously) two blouses, jeans and a dress.

http://levagabondage.blogspot.com/2015/02/hsf-challenge-blue.html

I made a 1930’s skirt!

http://trumpetsandtrimmings.blogspot.com/

Again I just barely make it. I tried out your stocking pattern! http://bugandbirdphotography.blogspot.com/2015/02/sarahs-stockings.html

Hi,

I made an Empire Pelisse (Open Gown)

http://jainieblogt.blogspot.de/

A day late, but I just posted about my competition of the blue challenge:

https://quinnmburgess.wordpress.com/2015/03/01/hsfm-2-1811-ufo-completed/

Best,

Quinn

Finally got my post done! (I blame my lateness on being sick)

A Renaissance doublet, a 1915 skirt, and a matching jacket

http://thedreadedseamstress.blogspot.com/2015/03/historical-sew-monthly-2-blue.html

Here is my contribution: https://teenagetailoress.wordpress.com/2015/03/02/historical-sew-monthly-february-challenge-blue/

A pair of 17th century pockets, hand embroidered with blue and gold flowers.

It’s done and my post is up! http://ajewintherain.blogspot.ca/2015/03/hsf-february-challenge-blue.html

I made a teens era corset. It was full of failures that’s why it took me soo long to finish it : http://thehouseofoldfashion.blogspot.com/2015/03/hsm2-niebieski-gorset-1910-hsm2-blue.html

Rather late blog post of a rather late project: https://caddamsbetraktelser.wordpress.com/2015/03/12/hsm-2-blue-late-post/

And I also have to say that your blog post about this challenge is fantastic! I’m a big fan of dyeing myself and dye history is very interesting. On my to-do-sometime-in-my-life-list is to successfully dye with woad – all my indigo dyes have gone well, but we failed miserably with woad the only time I’ve tried it!

https://wandabvictorian.wordpress.com/2015/02/16/challenge-2-blue/

My blue silk 1876 corset is finally done! Blog post: http://isabelnorthwode.blogspot.ca/2015/04/blue-1876-corset-finished.html

Better late than never, right? =)

[…] Legèrement en retard pour ce mois-ci, voici tout de même mon entree pour le challenge « Blue » du Historical Sew Monthly. […]

[…] de mon corset pique. Dans les semaines qui viennent je vais me mettre au challenge Blue du Historical Sew Monthly (une jupe 1830 à carreaux bleus), je vais coudre la robe de soiree d’Elsa (en pièces […]

So late for this challenge, but I came in late to the Sew Monthly! I made a 1860’s corset with “light periwinkle” silk flossing:

http://returningvintage.blogspot.com/2015/05/the-corset-is-completed.html

Finally, I actually got round to posting one of my challenges!! Here is my 1860s garter…

I combined January and February’s challenges so this is a blue foundation garment.

http://bygone-elegance.blogspot.co.uk/2015/10/historical-sew-monthly-january-and.html