When I first became really interested in fashion history in my early teens, and poured over historical costuming books and museum catalogues and saw mentions of sequins and spangles I assumed they were the same thing, and that ‘spangle’ was just a posh term for a sequin. As I studied textiles in university, and began working for museums, I realised that museums generally use very precise, specific terms (hmmmm…I wonder where my love of terminology comes from!), and that a spangle and a sequin might be different things.

As I’ve researched sequins and spangles I’ve realised that the use in terminology is sometimes very specific and precise, and that sometimes the terms are used interchangeably (see: how to make a fashion historian grumpy).

Many costume books use the terms to mean exactly the same thing, as do some museums. Some sources that make a distinction describe a spangle as a sequin with the hole at the top edge, rather than in the centre. Other sources describe a sequin as any decorative disk, while spangles must be metal – so all spangles are sequins, but plastic sequins (as we get today) are not spangles. To make things really confusing, some sources say spangles are circular, and sequins can be shaped, and others say exactly the opposite!

Gah!

Which is right? When in doubt, go back to the history, and work from there.

Spangle was the English word for decorative metal disks in the 16th-early 19th centuries (and possibly earlier). In this period these disks were almost always made by taking a very thin gold (or other metal) wire, and twisting it around a narrow rod to form a very tight spiral coil. The spiral is then snipped in a line all the way up, so that it falls apart in dozens of C shapes or jump rings, which are hammered flat, with only the tiniest gap at the opening of the C.

The other option for creating a decorative disk is by punching shapes out of a sheet of metal, and poking holes in the centre. These could be created in a variety of shapes (while coiled spangles can only form circles), and had holes only in the middle, with no line or gap, however subtle. Decorative disks formed in this fashion are usually called sequins, not spangles.

So, based on historical precedent: spangles are formed by coils and have seams, and sequins are solid disks. This is the most consistent usage I can find in textile books and museum catalogues but it is no means universal.

Sequin is regularly used as a generic term for a decorative flat metal disk. Not all museums make the sequin/spangle differentiation: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, identified almost all its disk-decorated items as being decorated with sequins, while many of its earlier items almost certainly actually decorated with seamed disks (i.e. spangles). Spangles are also sometimes used as a generic ‘decorative disk’ term, particularly in British English. One group that does almost invariably uses the ‘spangles-are-coiled, sequins-are-punched’ distinction is embroiderers.

Historically, I’m able to find instances where both terms are used in advertising from the 1890s to the 1930s, such as this 1901 ad for ‘spangle and sequin nets‘ being sold in preparation for a royal visit to NZ, or this one from 1903, or this one from 1913 (with a fashion image that may show such a net!). Unfortunately it’s not clear what the difference between a spangle net and a sequin net was at the time. Both are mentioned in newspaper descriptions of garments worn to gala events, such as this Tennis Euchre Party & Dance in 1910 – in my mind I visualise the sequinned items as being quite closely packed and overlapping, such as the blue dress from 1909 below, and the spangled items as being quite sprinkled, as in the Lady Maude Warrander laurel dress featured in Janet Arnold.

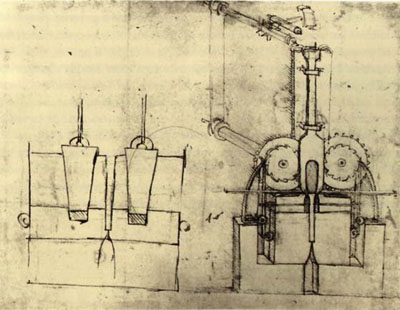

Sequins are an incredibly old form of decoration: punched metal disks used to ornament clothes dating to at least 2500BC have been found in India. Small gold disks were sewn onto the garments in Tutankhamen’s tomb, and Leonardo da Vinci drew a sketch for a sequin-making machine.

Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch for a device for making sequins. Sketch from the Codex Atlanticus housed at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

The name is much more recent than the ornamentation: it comes from the longest-minted coin ever: the Venetian Italian zecchino coin, debuting in 1284, and lasting until Napoleon conquered Venice in 1797. The coin was incorporated into a number of different traditional garments: punched and sewn to women’s vests and headdresses, as secure, portable valuables. The French pronounced the zecchino ‘sequin’, and when Napoleon rendered it obsolete as a currency, the name became applied to the use of metal disks as decoration.

While sequins are, as far as I can determine, much older, spangles are more common in extent garments until the Victorian era, as they were easier to make. Technological advances during the Industrial Revolution made punhced-disk sequins easier to create, and the introduction of non-metal sequins, in the form of celluloid sequins in the 1900s, electroplated gelatin sequins in the 1930s (which were exactly as durable as they sound – try not to sweat too much while wearing a dress decorated with them!) and more recently, plastic sequins, have almost completely supplanted coil-formed spangles.

The name ‘sequin’ entered English as part of the fashion for adopting French fashion works (such as fichu for neckerchief, and corset for stays) in the first half of the 19th century, just as punched disks began to replace coiled disks in popularity.

And what about paillettes? Generally paillettes are larger sequins, and are always flat (where sequins today can be faceted), though this, like sequins and spangles, isn’t a universal usage: sometimes paillette is uses as a straight synonym with sequin.

Pair of gloves with finger pieces extending into points, English, 1660s, Leather embroidered with silver and silver-gilt thread, silk ribbon and spangles, Victoria & Albert Museum, A T.225&A-1968

Waistcoat, England, Date- 1730-1739 (made) Silk satin, silver thread, spangles, silk thread; hand-sewn and hand-embroidered, Victoria & Albert Museum

Fan, third quarter 19th century, American, cotton, sequins, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1937, C.I.37.46.21

Evening Dress, 1909, Callot Soeurs, Paris, Silk mesh embellished with celluloid sequins and paste gems, Gregg Museum of Art & Design, 2003.014.208

Further reading:

A History of Sequins from King Tut to the King of Pop, Smithsonian Magazine

After Tutankhamun – a description of the sequins in his tomb

Wow, fascinating! Thank you.

So interesting! Thanks

As long as they aren’t ‘sequence’ I’m happy :). great post Leimomi!

Haha, too true!

Oh, I love these little details!

Thanks for posting this. I did not know what the distinction between a sequin and a spangle is. Nor did I know King Tut wore sequins. Though I did know that the making and wearing of sequins goes a long way back–sequins were found on the remains of the Mammen (10th c. Viking) cloak, for example.

King Tut is often cited as the very first example of sequins (and by often, I mean in almost every other article on the history of sequins in the internet 😉 ), but they go MUCH further back. I did not know about the Mammen cloak though! That’s fantastic – not at all our usual image of Vikings!

Hooray for a terminology post! I love little bits of sparkle, even if the terminology is rather inconsistent. 🙂 Combined with the coin minted for 513 years (!), the Leonardo Da Vinci sketch, and all those lovely examples, (including what may be the most flamboyant waistcoat I’ve ever seen), this was a delightful post.

Thanks Leimomi. Always learn something from you.

May we see a photo of the gown you mentioned with the gelatin/metalic plate sequins. Sounds like it was an historic piece of clothing? I couldn’t find an example of that type of sequin in the Smithsonian article.

Linda

They were used on numerous garments, but because they are so unstable there are very few gelatin sequin garments left. I’ll try to see if I can find one.

Not a garment, but the ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz are covered in gelatin sequins. The Smithsonian has a pair.

Thanks dear. Keep up the excellent work

L

Neato Mosquito! And you solved a puzzle for me: in the 1001 Arabian Nights tale, they talk about being paid in “sequins” (I think, I was a kid when it was read to me). I was so confused-those little shiny spangly bits on dance costumes? They are WORTH something!? Now I know that they were Venetian monies.

Love these terminology posts. Ok, I have an idea that struck me a week ago: What is the difference between “stain” and “dye”. Besides intention, why can you get stains out, but not dyes? If anyone knew, you would…

This was very intersting reading thank you 🙂

In my sparkly world, paillettes are the big jobbies, with a hole off centre so they hang loose. Also known as Penny Sequins. And I just spent many hours sewing small round, flat but also faceted crystals onto a wedding dress using tiny seed beads. They were called sew-though crystals which I think is a very boring name!

Thanks for the interesting read! I knew of the ‘punched out of a sheet hole in the center’ type, but not the other way of constructing these. Learned something new today :).

There is a room at Knole House in Kent called “The Spangle Bedchamber” – can you IMAGINE? An entire bed covered in spangles….

That sounds amazing and terrible! Something to add to my Europe wish-list!

I love your technical and educational posts! Thanks for writing them!

Fascinating! Gosh I love sewing trivia and history. I would probably have thought that sequins were always applied flat whereas spangles sound more like they hang and have movement.

Gelatin sequins – I would be a sticky mess! But I would love a sequinned fan!

In one of my many, MANY books on Venice (sadly I can’t remember which one), there was a chapter on the number of Venetian words which have their roots in Arabic, courtesy of Venice’s trade routes. One of them was the word for coin, which the book said gave us the word for sequin, so I assume this was ‘zecchino’.

It ties in nicely with the fact that middle eastern dancers often sewed coins onto their costumes; for the sparkly effect and to keep their money close to hand.

I always thought the difference was that spangles were made of metal, while sequins could be made of other materials, and I didn’t know how they were made either. Thanks for enlightening me.

Well, that happens by default too, because there is no other material you can make the spangle technique from, but (as I found out) it goes a little further!

So fascinating, all of it; the methods of making and the terminology. You know I love the language parts of your posts. 🙂 In Czech, sequins (especially of the modern kind) are usually called “flitry”, no idea where that comes from, and then there’s “pajetky”, which is obviously paillettes. They both seem like fairly recent developments; I wonder what an older word would have been?

The use of coins also reminded me of an episode in the life of Czech traveller Alberto VojtÄ›ch FriÄ, who got along mostly famously with South American Natives – in part because of that one time he proved his worth to the community by being able to make holes in coins a lot faster than others.

Goodness the amount of work you put into educating the rest of us. Thank you! (again). Jaqcui Carey mentiones in her books on 16-17th C embroidery the word “oe”. The examples pictured of extant articles have those little c-shapes, often fastened with three stiches, though the third mostly just covers the little gap.

Oh, how fascinating! I shall have to look that up!