Yesterday I told you the history of Kalaupapa Peninsula, and I promised to tell you of my trip down to the Peninsula today. As I tried to write this post, and select images to go with it, I realised I could never get all the words into one post, much less the images. So this is part 1 of 2 of my trip – day 1.

All my life, Kalaupapa was there: just over the mountain, just down the pali (cliff), visible from the lookout, as unreachable and unattainable as Paris, for all it was so many thousands of miles closer. I couldn’t visit it as a child under 16, and as an adult I couldn’t visit it without an invitation from someone who lived and worked down on the peninsula, or as part of a tour. I didn’t know anyone who worked at Kalaupapa, and I didn’t want to visit it as a tourist.

Every trip home to Hawaii I thought of giving in, paying for a tour, and going down just to see that bit of my history, but the time never seemed right. Then this visit, once I had arrived on Moloka’i, my mother mentioned, quite casually, that the new archeologist down at Kalaupapa and her husband were Baha’is, and friends of my parents, and it might be possible for us to go down and visit them.

And, as it turned out, it was. On my very last weekend on Moloka’i, Mary Jane (the archeologist) secured permits for Mum and I. Dad stayed home to take care of the farm and watch out for the ducklings that were due to hatch, and Mum and I headed down the Pali trail.

I should let you know at this point that one of the many things that Mum and I have in common is a phobia of heights. Tackling the hike was quite an undertaking for us (I fully expected to spend the entire walk alternating between chanting prayers and simple ‘not going to die’ pleas under my breath), so visiting Kalaupapa was a commitment in many ways.

As it happens, the trail isn’t as bad as I had thought it would be. Lush vegetation hides the worst of the dropoff views, and the scariest parts have been upgraded with bridges and protected with guardrails.

At least we were hiking though. The alternative way to get down the trail is to take a mule. In earlier times mail and supplies were taken down to the settlement via mule, and the tradition has been kept alive by the Moloka’i Mule Ride, which conveys people down to Kalaupapa for the tour. We passed the day’s tour as they were coming back up, and I did not envy them one iota.

The trail wends its way down the cliff-face via 26 switchbacks, each marked with a plaque, so that you can count your way up and down (and possibly to help you identify where you are if someone gets hurt and you need to go for help). In addition to spectacular views, the trail is marked by stunning examples of native vegetation, from the red lehua flower (the Hawaiian cousin of pohutakawa), to the endangered native Hawaiian hibiscus, to the extremely rare Alula, which has less than 65 extent species.

Seeing an alula was a privilege in itself. The one along the trail was just about to flower, and was protected from invasive foragers like goats and deer by fencing. You can see it in the fenced area just parallel to Mum’s glasses in this picture:

As we descended the trail, the mist blew away from the peninsula, and it got hotter and hotter as the cool upland forest gave way to more open coastal forest. By the 26th switchback we were extremely hot, and extremely grateful when the endless steps gave way to more level ground that wound through the last gentle incline which dropped up to the sea.

As we had descended the trail the sound of the ocean crashing against the cliffface had grown louder and louder, from a faint whisper at the top, through a dull roar, and finally, at the bottom, we turned away from the cliff and came out at a long black sand beach, with the characteristic swish of waves carrying tons of sand with each rise and fall of the water. Behind us were the cliffs, stretching out along the northwest shore of the island, and the pali trail, rising to the uplands. In front of us was Kalaupapa.

We were collected at the trail’s end by Mary Jane, lovely and welcoming, ready to show us the world she is helping to understand and protect. I got to experience the classic Hawaiian (and especially Kalaupapan) mode of transport: ‘catching air’ in the back of a truck, with prerequisite dog.

Riding in the back of a truck may be the best way to see all the amazing views that Kalaupapa has to offer. In the image above you can just see the modern view that amazed me most. Enlarge the picture, and you should just be able to see the electricity and phone cables coming straight down the pali at the point of the deepest cleft. They go down at an almost vertical angle! There must have been some pretty impressive moments with a helicopter to make that happen.

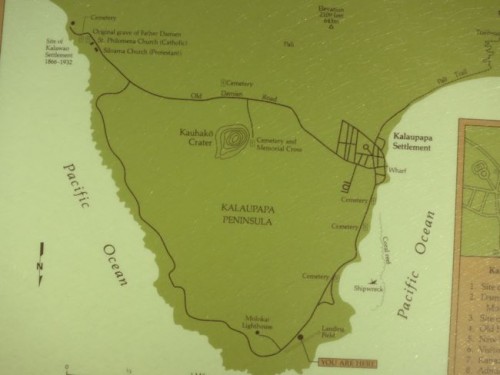

Everything at Kalaupapa is amazing, from the natural beauty, to the ancient history, through to the 19th and early 20th century events that it is most famous for, to the modern engineering that has tried to connect it to the outside world. First, we went to see some of the natural beauty. Kauhakö (that should actually be a straight line over the O, but I can’t figure out how to do that in WordPress) Crater is what remains of the low shield volcano that formed the peninsula: a low rising hill punctuated by a deep crater. At the floor of the crater is a tiny lake, at 800 feet deep, it’s probably deeper than it is wide. On the day I visited it was a deep, olive green, but on other days it glows blue, or dark brown, or a range of other hues.

On the hill around the crater are example of the two most common human artifacts on the peninsula: stone walls and gravesites. Everywhere you look in Kalaupapa are stones arranged to form walls, or piled in piers to mark the thousands who were sent there not to live, but to die.

Memorial stone for Kahalekumano, born April 1 1855, died Dec 22, 1893, on the edge of Kauhakö Crater.

Beyond the tragedy of the story they tell, and their abundance, two things struck me about the gravestones that are so prevalent at Kalaupapa. First, so many of them are in Hawaiian. The Hawaiian language lingered as the predominant spoken language much longer at Kalaupapa than in other places in Hawaii, so many, many gravestones bear the legend ‘He Kiahoomanao‘ (this is the memorial marker) no (of) ______, hanau (born) _______, make (died) _______. Second, for all that so many of the gravestones are in Hawaiian, and Hawaiian’s were the most succeptible to leprosy, its clear from the names on the gravestones that people of every ethnicity, and every walk of life, caught the dread disease and were exiled to Kalaupapa.

From the crater we headed down and around the curve of the pali, to Kalawao, the original site of the place of exile for Hansen’s Disease patients. While the Kalaupapa township side of the peninsula had been warm and dry, the problems with Kalawao were immediately evident. It lies in perpetual coolness and mist, all but abandoned save for one orange cat which has appointed itself the guardian of Damien’s church, waiting daily in front of it to greet the tour group.

After stone walls and gravesites, Kalaupapa is marked by churches. Religion had a profound impact on the early patients, providing them with care and succor, and sometimes even hope. Kalaupapa is the second least populous county in the US, but it surely must have the most houses of worship per capita.

The churches at Kalawao are no longer active today though: the settlement at Kalawao was abandoned in the 1930s, with all the patients moving to the warmer end of the peninsula. The population of the peninusla has dwindled on a yearly basis since then, and all the buildings but the church were allowed to fall into disrepair, the jungle slowly taking over the old boys home, the leprosarium, the houses and cottages that would have surrounded the churches. Nothing remains but the stone walls and the gravesites.

From Kalawao, we turn away from the pali, heading down and around the curve of the peninsula. We stop at the rocky shore where patients were unloaded, left to fend for themselves without provisions or a word of comfort.

In a place desperate with sadness, with longing for life, this is perhaps the saddest point: the place where one life ended, before patients had a chance to realise they might be able to make another, very different, life.

The amazing, wonderful thing about Kalaupapa is that after the first few dreadful years, there was life, and joy, and the full breadth of human experience. Visitors to 19th and early 20th century Kalaupapa came expecting a place of utter desolation and despair, and found instead the resilience of the human spirit. Robert Louis Stevenson talked of the beautiful things he had seen in the world, and especially of the girls of Kalaupapa being ‘not the least beautiful among them’ by far, and how the young boys in the boys home were like boys everywhere: eternally picking up one amusement and fad after another, one day enjoying jacks, the next all learning to play the ukulele, then abandoning those for ballgames. Jack London found himself laughing himself silly at the Fourth of July races at Kalaupapa, feeling that one oughtn’t to laugh in such a place, but unable to resist the infectious joy of the crowd.

Kalaupapa today is a balance of the sadness that every person brought with them, the sadness of all those gravesites, the unutterable longing for life that you hear in every wave, in every breath of wind, and the peace and joy that people found, despite it all. The township of Kalaupapa is both exquisitely charming: a picture postcard of what small-town Hawaii might have been in the ’40s & ’50s, and slightly desolate, with too many empty rooms and abandoned lots. The whole peninsula is too full of the memories of lives with broken ends: all those people who were forced to leave their homes in the 1860s to make way for the patients, all the patients who were forced to leave their homes to come to Kalaupapa, all the children born there, who were taken away to protect them from catching leprosy.

The whole peninsula aches with longing, perhaps most of all in the long room: a long, narrow building with five doors, two at each end, and one in the middle. The room is divided along its entire length by a table, but in the early 20th century it was also divided by a heavy fence running the length of each room. On one side, the patients came in, on the other, their visiting families. They could see each other, but never touch each other.

The long room is freshly painted, but a layer of dust lies on all the ledges. It’s both cared for, and abandoned: a rather heavy metaphor, but there it is.

As haunting as the place itself…thank you for this entry.

I knew nothing about this place…now I do and its given me plenty to think about so thanks for writing about your journey there.The photos add to it as well.

Thank you. This is an amazing story and one I had not know about previously. Very powerful.

Good writing, moving adventure.

Ok, so maybe this is too serious a question, so if it is, then feel free to delete my post. These tours people can take–Do the current residents consent to them? Is it a happy thing, or is it like the Polynesian Cultural Center which amounts to little more than human zoo exhibits?

And then I have a question about the clothes. I know that my friend Makia went through a hard time emotionally when he lost much of his hands’ usefullness, and that not everyone experienced the disease in the same way. But how did those with progressed Hansen’s disease cope with clothes? Were there a sort of uniforms? What did they do to help those who couldn’t do buttons or zippers?

Hi Elise,

It’s a serious topic, and deserves a serious question. Kalaupapa County Law prohibits anyone but former patients from owning/running a business in the county, so the tours are patient owned and run. I’ve never been on one, but from what I have heard, they are excellent: told from the heart by someone who experienced part of the story. The only drawback is that they are a bit brief (three hours to do the whole peninsula). I believe the current tour guide is the wife of a former patient, though there must be backup tour guides as well. From the stories I have heard, the tours are very much like listening to Makia ‘talk story’: a balance of honesty, pathos, hope, and Hawaiian humour. I’ve never heard anyone say anything about the tours being at all disrespectful, and they certainly aren’t the horrible human zoo things!

I believe the National Park Service is currently looking for an ‘interpreter’ to help develop the visitor experience (sorry for the museum jargon) as the park makes the transition from the last of the patients to whatever it will be after, but it’s hard to find someone with the training and the cultural background.

The one drawback to my trip to Kalaupapa is that we went over the weekend (we were meant to go Sun-Mon, but there was a mix-up with the permits, so we had to go Sat-Sun, because that’s what they were for), so we didn’t get to go to the museum. Mary-Jane (the archeologist) says that one of the truly amazing and inspiring things about Kalaupapa is the devices patients made to cope with their disabilities. They are a real testament to ingenuity and adaption.

There certainly weren’t uniforms, though in the 19th century most women would have worn holoku, which are easy to get in and out of. A lot of patients also lived in group homes with nurses and helpers.

Dreamstress,

Thanks for the considered response. I may or may not have kept clicking back to read the response to the question about human zoos.

I don’t know how things are outside of the US, but I remember noting when I was 7–and unable to ‘unsee’–that Amerindian artifacts are not displayed in the large history museums, but are rather displayed in the *natural* history museums–with the animals! It’s not just First Nations, either. When I visited the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in 2011, there was an exhibit about the peoples of the African continent.

The idea of a group of people taking control of their own history, however, seems very cool. Makia often talked about his life (you can find his stuff if you poke around talkstoryradio.com), but I never heard much about tours, and wondered if it had the same kind of vibe and scope as the PCC or US natural history museums.

It is wonderful–to think about a tour (however short) that puts all the layers into the narrative that you describe. It would have been a really neat thing to have seen the museum, and to experience all the creativity that sprang up in Kalaupapa. Then again, it gives you a chance to get creative yourself and imagine what there is!

Thank you for also describing the clothes and how people would help each other.

And I’ve liked the term ‘interpreter’ what translation work I’ve done requires a fair bit of cultural knowledge even at the language-level. So I like a term that connotes the wide range of cultural experiences going into the planning of a musuem/park/sacred place/etc. I wonder if any of the residents are part of that planning process, too.

I started reading your blog to see the pretty clothes. You have given us so much more. Thank you from the heart.