Brown linen is the term used to describe unbleached linen in the 18th and 19th century. ‘Brown’ linen could either be finely woven, high quality linen that would be bleached before being sold, or rough, coarse linen that would be sold brown.

Rather than pre-bleaching the linen yarn, cloth was usually woven brown, then sold to bleachers, the price based on the quality of the thread and weave, and then on-sold to fabric merchants and customers. Heavy and course linen would probably remain brown for use in cheaper clothes, as bags and for rough use (in 1803 Merriweather Lewis purchased from Richard Weavill, a Philadelphia upholsterer, 107 yards of brown linen to be made into 8 tents for his cross-continental exploration with William Clark), finer linen cloth would be bleached white.

Interior of a 1765-1775 sacque-back gown – the lower sleeves are lined in brown linen, sold at Augusta Auctions

The Impact of the Domestic Linen Industry describes the how the town of Banbridge in the county of Down had grown up from a cluster of houses in 1718 to a prosperous market town 20 years later entirely around the sale of unbleached linen, and how “the weavers brought their webs to the weekly brown linen market, where dealers known as linendrapers purchased them for bleaching and finishing.”

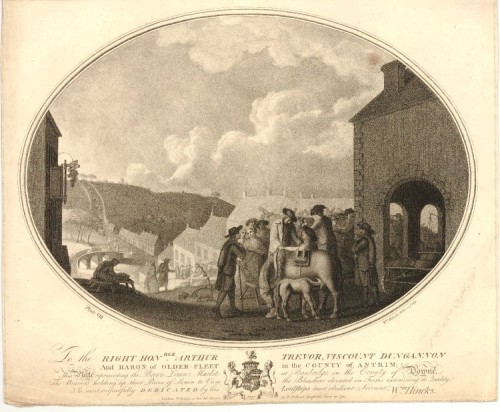

The Brown Linen Market at Banbridge, in the County of Downe, 1791, The British Museum

Most of the mentions of specific brown linen garments in the 18th and 19th century come from two sources: lists of stolen clothings, and advertisements for runaway slaves in the American South. The latter is quite understandable: brown linen was a cheap fabric, so slaves, at the very bottom of the societal ladder, were most likely to be clad in the cheapest cloth. Mentions of stolen clothing are more interesting, because they illustrate how valuable fabric was in the 18th and early 19th century, when even a “man’s shirt of brown linen much clouted and worn” was worth stealing in the 1760s.

In July 1804 a slave named George fled Charleston in “brown jacket, brown calico waistcoat, and brown linen pants with suspenders.” Three decades later one Willis ran away via steamboat from New Orleans wearing “white shirt, brown linen pants, a blue frock coat and a black hat.”

In the 18th century the brown linen worn by slaves for shirts, chemises, petticoats and summer clothing was invariably osnaburg (also spelled ossnabriggs or oznabig). Onsaburg is a heavy, coarse plain-weave fabric having approximately 20-36 threads per inch. The name coming from the German city of Osnabrüch where a course linen cloth was manufactured in the early 18th century. By 1740 osnaburg was being manufactured in Scotland and by 1758 2.2 million yards were being made, mainly for export. Some was exported to England or the continent, but most went to the Americas, and most of that was used for clothing for slaves.

It was so popular for cheap labourer’s clothing that when cotton replaced linen as the most economical fabric in the early 19th century the name became applied to a cheap cotton fabric of a similar weight and weave. An 1835 story describes a slave wearing an “onsaburg chemise and coarse blue woolen petticoat”. Similarly in 1853 The Lofty and the Lowly mentions a similarly dressed woman in an “osnaburg chemise, and linsey-woolsey petticoat.” By this time onsaburg could have been either linen or cotton. Onsaburg is still readily available (Jo-Annes in the US sells it) for those wanting to replicate early 19th century lower-class in America.

Cotton onsaburg for sale here

Unbleached linen was commonly called brown linen well into the mid-19th century. In 1824 “brown linen cambric” was advertised for sale in the New England Farmer, and in 1840 The Workwoman’s Guide describes “A Gentleman’s Worshop Apron…of Holland or strong white or brown linen.” In 1835 the British government passed “An Act to continue and amend certain regulations for hempen manufacture in Ireland”, which frequently describes “Brown or unbleached or unpurged linen yarn” and proscribes the measurements of cloth “when brown and before the same shall be bleached.” Brown linen was sold in New Zealand in the 1860s. Even as late as 1895 the Montgomery Ward & Co. catalogue was selling “brown (unbleached) linen” in 50 yard lots. By the mid 19th century the brown linen that is being sold is clearly intended to be used only as rough cloth.

Brown linen finally ceased to be a poor-mans cloth in the later 19th century with innovations in bleach technology and the rise of cotton as the cheapest, most readily available fabric. Improved bleaching technology throughout the early 19th century made it so much cheaper and easier to bleach linen that white linen of the same quality was hardly more expensive than brown. In the first part of the 19th century the cheapest bleaching methods weakened the cloth and people “loudly complain of the rotten state of the linens being retailed in a grey [partly bleached] state in the streets, alleging they give no wear from being bleached with lime.” By the end of the century white linen was as common as brown, and cotton was a far cheaper fabric than linen, so linen of all colours achieved a bit of status and unbleached linen suits and dresses were worn by the wealthy for summer clothes.

Day dress of unbleached linen with green silk underslip, 1901-2, Misses Leonard, St. Paul, US, Minnesota Historical Society

Sources:

Crawford, W.H. The Impact of the Domestic Linen Industry. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. 2005

Embleton, Gerry and May, Robin. Wolfe’s Army. London: Osprey Publishing. 1999

Franklin, John Hope and Schweninger, Lauren. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999

Katz-Hyman, Martha B, and Rice, Kym S. (eds). World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the US. Santa Barbara California: Greenwood, 2011.

Saindon, Robert A (ed.). Explorations Into the World of Lewis and Clark, Volume 2: Essays from the pages of We Proceed On: the Quarterly Journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. “Along the Trail”. R.R. Hunt. Great Falls Montana: Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. 2003

Styles, John. The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. 2007

The workwoman’s guide, containing instructions in cutting out and completing articles of wearing, 1840.

Another really interesting post – ‘Osnaburg’ was new to me.

So interesting! Particularly the bit about weakening through bleaching, because I recently cursed linen for its (in my experience) fragility. Perhaps you know more – can dye weaken linen? My rant is here: http://makeitfakeit.wordpress.com/2013/01/24/a-letter-to-linen/

Dye weakens linen, but it sounds to me like you managed to buy some cheap linen 🙁

There is also a problem with modern linen vs. historical linen. Historically linen was water retted (soaked in water to dissolve the squishy plant stuff from the flax fibers), but today most (probably all, I’ve not seen or heard of a source for water retted linen in at least a decade) linen is chemically retted, which weakens the flax fibres. Linen is also sometimes chemically retted and then mechanically processed, which means not only are the flax fibres weakened by the chemicals, they are then chopped from long strands into short strands, and re-spun together, resulting in much shorter, weaker threads.

In addition, much linen sold today is a linen-cotton blend, which is (weirdly, I haven’t worked out the whys of it yet) weaker than either pure linen or pure cotton. My Mad, Bad & Dangerously Green shorts and Love at First Flight dress are both made from linen cotton blends, and are both very weak fabric for their weight and weave. They were both very expensive fabric, from a company that should be quite high quality.

Finally, one of the problems with linen is that a lot of the linen modern linen that is sold as handkerchief linen, or lightweight linen, achieves its lightness not with finely spun threads (much harder to get with chemically retted linen), but with a loose weave, which equals weaker fabric. That’s probably part of what went wrong with your dress 🙁

There isn’t much of a solution to all of these except to test your fabric when you buy it. How loose is the weave? Could it be ripped by tugging? Does it warp and un-shape when you manipulate it?

Hope some of this helps – it reminds me that I’ve been meaning to write a post on linen for at least a year and just haven’t gotten around to it!

I had the same problem with a linen/cotton dress. Damn thing split along the zipper seam within two weeks, even though there was no strain to speak of.

Oh no! More bad fabric.

I haven’t had any splitting with either of my linen/cotton garments, not in the fitted bodice of the LoFF dress or in the MBDG shorts, which are quite snug and get a lot of wear/stress. I’m just aware that the fabrics aren’t as robust as they should be for their weight.

What brands or mills or shops do you recommend for the newbie? You know, like you recommended in your thread section?

Thank you for such a thoughtful reply!

yatesbleachery.infoThank you–this was interesting and wonderfully detailed!

I’ve worked with cotton osnaburg–it has a soft hand, usually, from its relative lack of treatment, although I’ve often found little bits of tough brown material spun into the fiber–waste from the cottoon plant, I suppose.

The textile referred to in the southern US as “domestic” and elsewhere as muslin, although it’s nothing like Jane Austen’s muslin, looks to me as if it’s another “brown” fabric–it’s typically sold as “unbleached”.

I’ve been told that the unbleached cottons, and even more so the linens will lighten as they are washed and dried in strong sunlight; I don’t know how true this is, or how much they will be lightened.

Also, in the world of “things change, except they don’t”, there are still bleacheries–I’ve shopped in the retailed outlet section of Yates Bleachery, which is just south of Chattanooga, right over the Georgia state line in a town called Flintstone. They do a lot of different fabric finishing processes the old bleacheries couldn’t imagine. They still do bleaching, though.

They do lighten in the sun. My great-grandmother forced her daughters to wear almost nothing but white, so that they could save money during the depression by drying the dresses out in the sun for the free ‘bleach’.

Not only do they lighten in the sun, but most 1930s era dyes faded badly in the sun, so you had to dry them out of the sun or they would fade – white clothes made a virtue out of this drawback.

Aha! The stuff that is called muslin in the US but isn’t Jane Austen’s muslin? I wrote a tw-part terminology post about that, and why it is!

Calico, Muslin, Gauze part 1.

Calico, Muslin, Gauze part 2.

Yes! I remember those posts now–unbleached muslin/unbleached domestic are the US names for textiles elsewhere called calico.

Also, as Miss Felicity has a cameo appearance in the first of those posts, let me mention that cats of her ilk are sometimes called chatte d’Espagne in France. I don’t think that’s textile-related, though. Also, calico cats are the state cat of Maryland. I had no idea there was such a thing as a state cat.

Apparently there are state sandwiches. Things may have gotten a little out of hand….

I found this: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._state_mammals I think Kentucky wins with the most random one, as it has a ‘State Wild Animal Game Species’. It’s a grey squirrel. Texas though, insists on having a state large mammal, state small mammal, and state flying mammal. I like that Wisconsin has a dairy cow!

I wonder what the expensive linen stuff you could buy as souvenirs in Latvia (someone in my family has got something, but not me) is processed like…

It’s a fascinating process that was even made into a cartoon – the first cartoon with the Little Mole, that Czech cutie… we have a book, so I’ve known about the processing of linen since early age! Which makes this doubly nice, knowing I can still learn a lot. 😉

That first photo is my favourite kind of interior photography.

Oooh! I’ve got a friend in Latvia at the moment who offered to bring me back something from Europe, but I couldn’t think of anything. I might see if I can get ahold of her and get her to bring me a bit of Latvian linen to compare. I have old Irish linen which is beautiful, but apparently there is no longer an Irish linen industry. 🙁

There are still small tiny cottage industries who prepare linen traditionally, but only to sell in tiny souvenir pieces – no help for the average seamstress or historical costumer.

Isn’t that interior shot fabulous? I’ve started a pinterest board of interior costume images, but they are so hard to find! I love that the gown is so rough and patched inside – it makes me feel so much better about any untidiness in mine!

It’s quite possible that the linen souvenirs are just like that, cottage industry… I don’t even remember seeing fabric shops in Latvia, weirdly – I only remeber one I saw in Tartu, Estonia. Which is not to say there are no fabric shops in Latvia, rather perhaps that I moved in areas where there are none…

It makes me feel better and more relaxed, too. There are some interior shots on V&A that helped me relax about my handsewing quite a bit; this one would have been even better for that initiation. But, generally, there are far less interior and construction shots than I would love to have!

One of my exes had fabulous linen sheets. He was from Croatia, and they had been made there. I don’t know if the war had anything to do with it: Had they been made pre-war and then took care of? Or were they newer? What is the economy like?

Anyhow, until recently, Croatia made pieces large enough and common enough to be part of everyday living.

No idea about Croatia! Actually, no idea about Czech Republic, either – the offer in shops would suggest something, and then you go and find out there’s still a thread maker that’s going fairly strong… It puzzles me.

linas.ltI tried and googled and found a Lithuanian company, http://www.linas.lt – not Latvia, but close enough for your friend, perhaps. They seem to have a shop in Vilnius. Not sure about the process, but they proudly proclaim to fit some ecological standard, so who knows…

A tip for my next time in the Baltic countries, too, which I’m sure will come one day. 😀

My partner lives in Tallinn, Estonia!! I could ask him to check the linen shops out for you, and send a swatch/sample. (we also have a mutual friend who lives in Vilnius…)

There is no Irish linen? I read some where that art historians often have to replace the backing of paintings, and they have to match the fabric of the canvas with what would have been around then. So if there is no Irish linen, what do art historians use when replacing the canvas of an old Irish painting?

Ahh, this brings back happy memories of researching the Mycenaean linen industry for my Honours dissertation.

Hi! I just wanted to say that I really enjoyed this little article! Also, I’ve been enjoying your blog for years and I realized I never have actually popped on to say “hi,” so it’s about time I did!

Cheers,

Sarah