Synchronisity is an amazing thing. I wrote this post in January of 2012, and got it completely finished all save one last quote from Queen of Fashion that I wanted to add, and then got distracted and never published it. And then, at the beginning of August, I came across my not-published post, and went to the library to borrow Queen of Fashion, only to find it was out. Literally two days later Kendra at Demode posted about making a robe de coer and started the 2014 18th Court Ensembles Project.

Well, Queen of Fashion has finally come back in, and just in time, because I’ve finally been tempted into joining the Court Ensembles project. I actually have the beginnings of a 17th century robe de cour in my UFO pile, but it’s not 18th century, so instead I’ll be making this:

Alexis Simon Belle (1674—1734) , Portrait of Louis XV as a child pointing to a portrait of his fiancee the Infanta Mariana Victoria of Spain, circa 1723

Obviously I mean Mariana Victoria (yellow-gold brocade….rrrrow), though if things go really well Mr D is going to find himself sporting a russet velvet justacorpse.

So, now that I’m making one, what is a robe de cour? Kendra has already posted about the basics, but you can never have too much terminology information! (or at least that’s what I think), and besides, I already had this pretty much written.

A robe de cour, also called a robe de corpse, grand habit, grand habit de cour, and in English, the stiff bodied gown or straight bodied gown, was the formal court wear across much of Europe, and most particularly in France, throughout the 18th century. It was based on a design implemented by Louis XIV, the Sun King, in the 1680s. It consists of a stiff, boned bodice which laces up the back, a skirt, a separate train worn either at the waist or falling from the shoulders, and detachable lace sleeves.

Louis XIV admired women’s decollate and shoulders (really, to the point where he refused to allow even the older women of the French court to cover them, in church, in the middle of winter) and despised the informal loose robes (mantua) that were becoming stylish at the end of the 17th century. To counter them, he had the off-the shoulder, fitted bodice robe de cour designed and made mandatory wear for women at all formal events at the French court. In 1704 he angrily ordered two noble ladies from the theatre for daring to show up wearing something other than a robe de cour.

Madame the Duchess of Orleans was much in favour of the robe de cour at the turn of the 18th century, claimed to own no gowns but robe de cour and riding habits, and said:

At Versailles which is considered the royal residence, everyone who comes into the King’s presence or into ours , must be in full Court dress, but at Marly, Meudon, and Saint-Cloud mantuas are worn, also for travelling. I find Court dress much more convenient than mantuas, which I can’t endure.

A robe de cour is notable for the stiff boned bodice worn without stays. Louis XIV based the robe de cour on the gowns that had been fashionable when he was a young man in the 1660s & 1670s, like the ones I used as inspiration for the Ninon gown.

Élisabeth (Isabelle) d’Orleans, Duchess of Guise by Beaubrun in the 17th century fore-runner of a robe de cour, 1670

The bodices of robe de cour have wide, off the shoulder necklines, but the based on extent portraits, the neckline still manages to be relatively modest, and few portraits show any visible cleavage. Robe de cour were often worn with an extra piece of lace above the low neckline of the bodice itself.

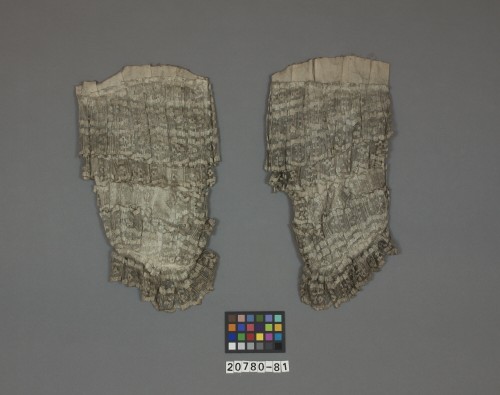

Below the neckline were very small sleeves of the same fabric as the bodice, and the rest of the arms were covered by detachable lace sleeves with rows of stiff, pleated lace.

The arrangement of the ruffles, and the shape of the lace sleeve, changed slightly from decade to decade, so portraits can be dated based on the style of sleeve.

Portrait of a Princess by an unknown German artist, 1740, the Royal Collection, UK

Though the robe de cour was worn without stays, the heavy boning that was built into it and the back lacing that held it closed meant that it was more constricting than stays. In a modern sense, we view visible garment lacing as risque – associated as it is with corsetry and undergarments. In contrast, in the early 18th century it was the pinned-on mantua, with its hidden closures and ability to be worn without a boned undergarment (and thus the implication that the wearer could undress and redress herself quickly), that was risque, and the back-laced robe de cour was the epitome of propriety.

Court bodice associated with Marie Antoinette ca. 1780-87, from the Musee Galliera

Though robe de cour were always made of rich fabrics, the bodices could be further ornamented with stomachers and jewellery (including jewelled stomachers). Diamonds, the favourite of Louis XIV, were often used, though many stones were used, both on the bodice, and the skirt. When Marie Leszczynska was married “the Fore-Sides of her Stays and her peticoat shinn’d with divers pretious stones.”

The shape of the skirt worn with the robe de cour had always changed with the fashions of the time, but the bodice, barring some very slight alterations in style, remained quite static. The only major change in the bodice style was a shift in the 1770s and 1780s from very low, scooped shoulder-baring necklines to slightly higher, squarer necklines that matched the current fashions. Compare the necklines of the extent green bodice below, with the earlier yellow bodice at the end of the post.

Robe de Cour sur le grand panier, cette robe est de gros de Naples et garnie de dentelle entrelassee de rubans noues de distance en distance, Gallerie des Modes, 1778; MFA 44.1354

Because the shape of robe de cour skirts change with current fashions. The first robe de cour were worn without hooped petticoats, as the panier did not become common in France until at least 1720. In the 1720s robe de cour had relatively restrained, conical skirts:

Le Mariage de Louis XV et de Marie Lecszinka dans la chapelle de Fontainebleau le 5 septembre 1725 Marie wears a blue robe de cour

In the 1760s the skirts become enormous, but very thin and rectangular:

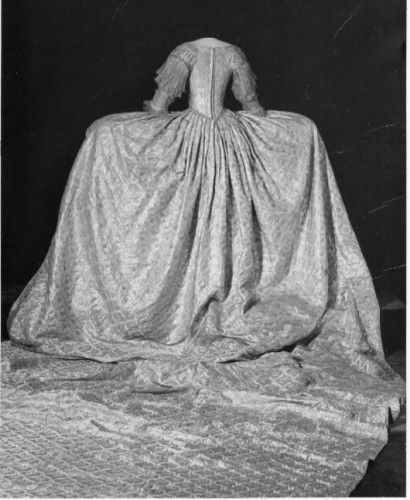

Sofia Magdalena’s wedding gown, robe de cour, worn at the wedding at the Palace Church November 4, 1766.

Martin van Meytens (1695—1770) Maria Carolina of Austria (1752-1814) 1760-70, Wikimedia Commons

By the 1780s, the skirts were not as extreme and rectangular, but they were laden with a profusion of trimmings.

Louise Élisabeth Vigee Le Brun (1755—1842) Description English- Marie Antoinette of Austria, Queen of France (1755-1793), 1783

There were also regional differences in skirt shape. In the 1740s-60s the English tended to wear a very rectangular hoop, where the French wore a hoop, that, while just as wide at the hem, was more sloping and less square at the corners.

The train of the robe de cour could be worn either from the shoulders, or from the waist, though the latter was more common. The length of the train was an indication of status: the longer the train, the higher the rank of the wearer. The etiquette of train wearing varied from country to country. In England one held ones train up, draped over one arm, as a sign of respect. In France, despite the much-remarked upon filth of Versailles’ hallways, one wore one’s train down as a sign of respect.

In France, throughout most of the 18th century the robe de cour was mandatory at all formal occasions in the presence of a royal. When presented, ladies wore a black and white (or silver) robe de cour, and the next day, they appeared at court in a coloured robe de cour.

M. Garsault in the 1769 Encyclopedia Description des Arts et Metiers, describes:

‘The day the Lady is presented to the King and Queen, etc., the bodice, train and petticoat must be black: bit all the trimmings are of lace, net, etc. The upper arm, except at the top close to the shoulder where the black sleeve of the bodice is seen, is covered with two flounces of white lace, one below the other, to the elbow. Under the lower flounce there is a decorated band (bracelet noir, forme de pompons). There is also a border of white lace around the neck-line and under that a narrow black tippet (palatine) also decorated from neck to waist: the petticoat and bodice are decorated with puffs, all of which are made from net, lace, etc., also gold.

‘When the day of presentation has passed, everything that was black is replaced by coloured or gold material. This style of dress has long been worn and has remained unchanged until the present day for ceremonial wear.

If the Lady to be presented is not able to endure the heavily boned bodice than she is allowed to wear a lighter one, covered with a mantilla, with the court train and petticoat. As the mantilla covers the upper arm the top lace flounce, which would not be seen, is omitted. The mantilla is made from any light material such as gauze, net, lace, etc.

There were occasions to wear other gowns, but leaving off the robe de cour was considered a privilege. In 1754 the Duc de Luynes wrote:

Two or three days before the Court leaves for Fontainebleau or Compiegne ladies are permitted to wear a robe de chambre. Those who are not travelling or do not go in the carriages of the Queen, Madame la Dauphine, or Mesdames, must always wear full court dress.

It was in the 1770s, that Louis XVI, influenced by Marie Antoinette who called robe de cour “obsolete and unbearable”, allowed women to wear modified robe de cour, with smaller paniers and shorter trains, and to wear robe a la francaise at all but the most formal occasions. In the 1783 he went further, and it became acceptable to wear a grande robe a la francaise (one worn with large paniers) in lieu of a robe de cour, except when a lady was being presented to the King, Queen or a Princess or Prince of the royal blood, and at ceremonial bals (unless, presumably, her health prevented her from wearing boned bodices).

The English term for the robe de cour was a rather literal ‘Stiff-bodied gown’. Mary Granville described the wedding of Anne, Princess Royal, to the Prince of Orange in 1734, and Anne’s gown of silver tissue:

The Princess of Orange’s dress was the prettiest thing that ever was seen – a corpse de robe, that is in plain English, a stiff-bodied gown. The peers’ daughters that held up her train were in the same sort of dress – all white and silver, with great quantities of jewels in their hair and long locks’

A portrait of Anne’s sister in law, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, painted at the time of Augusta’s marriage to Frederick in 1736 shows her in a similar ensemble of brocaded silver fabric which was probably her wedding dress. Silver robe de cour were the standard wedding dresses for royal brides across Europe in the 18th century, from Augusta to Catherine the Great to Marie Antoinette, among others.

Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, Princess of Wales (1719-1772) by Charles Philips, 1736, Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London, image via Wikimedia Commons

There is only one extent English robe de cour bodice that I am aware of, now in the collection of the FIDM Museum

Court Bodice, 1761, Helen Larson Historic Fashion Collection, FIDM

The robe de cour was never mandatory in England, as it was in France, and there was no occasion in which it was not acceptable to wear a formal mantua (one worn with extremely wide paniers, and from the 1740s onward, triple sleeve ruffles) in lieu of a robe de cour. The mantua, distinctive from the robe a la francaise because of its folded and pleated back and hanging train, remained the acceptable court dress in England long after the garment went out of fashion for any other use. By the time this 1750s mantua was made, a mantua was unlikely to be seen anywhere in England except at court.

Formal English court mantua worn with French style hoops, English with French fabric, 1755-1760 (garment) 1753-1755 (fabric), Silk, silver-gilt thread, linen thread, silk thread, Victoria & Albert Museum, T.592:1 to 7-1993

The Austrians also wore robe de cour for many occasions during the reign of Maria Theresa, but when Marie Antoinette’s brother, Joseph II assumed power in 1765 he attempted to reduce the formality of the court costume in Vienna, and the robe de cour was seen less frequently. Before that, Austrian court costume had been heavily based on the French example, though they seemed to have a few regional quirks, my favourite being the elaborate robing ‘leis’ lappets (possibly the tippets described as palatine) worn by the Austrian princesses in many of their portraits.

Portrait of Maria Carolina of Austria (1752-1814) 1760s, Wikimedia Commons

The robe de cour was also worn by many other European courts, but the style was always defined by France, and the dresses often came directly from France. The gown that Marie Antoinette was ceremonially divested of when she went from being an Austrian Archduchess to being a French Dauphine had been made in France, and many other royal ladies sent to France for their robe de cour.

Not surprisingly, robe de cour were extremely expensive, and could cost thousands of livres. It took 20 to 22 yards of fabric (though this would be quite narrow widths). The tailleur de corps would make the bodice and train, the couturier the skirt, and the marchant de mode would provide the trim. Marie Antoinette was said to order 12 grand habits (robe de cour), 12 robe parees (slightly less formal robes with paniers), and 12 informal robes every season. Quite an investment considering that in 1787 a grand habit cost the equivalent of 2,000 days wages for a worker!

The French Revolution momentarily did away with the robe de cour in France, but the precedent it had set remained in other countries. The hoop was so much a fixture of formal English court dress, that a hooped dress remained mandatory court presentation wear until 1820, despite how ridiculous one looked when paired with high-waisted Regency fashions.

The detached train, the ultimate symbol of status, remained part of presentation wear at the English court into the 20th century, and its echos can still be seen today in the prevalence of trains in modern bridal wear. Speaking of trends in modern bridal wear, I’m not a personal fan of the trend for strapless dresses, but I suspect Louis XIV would have approved!

Sources:

Arch, Nigel & Marschner, Joanna. Splendor at Court: Dressing for Royal Occasions since 1700. Unwin Hyman: Sydney. 1987.

Buck, Anne. Dress in 18th Century England, B.T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1979

Hart, Avril and North, Susan. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Fashion in Detail. V&A Publishing: London. 2009

Riberio, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe 1715-1789. B.T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1984.

Riberio, Aileen. Fashion in the French Revolution. B.T. Batsford Ltd: London. 1988

Mansel, Philip. Dressed to Rule: Royal and Court Costume from Louis XIV to Elizabeth II. Yale University Press: London. 2005.

Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes: 1600-1930. Faber and Faber: London. 1968

Weber: Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. Picador: New York. 2006.

Another wonderful terminology post!

I found the combination of the high-waisted style with the enormous skirt of the poor Marchioness of Townsend highly amusing!

Thank you! Regency court wear is a particularly unfortunate – but amusing – genre isn’t it. Such an unhappy combination of styles!

I’m wondering, has anyone ever tried to recreate Regency court fashion in film? 😀

The remarkable HBO mini-series “John Adams” carefully attempts authentic reproductions of the clothing of Abigail Adams from a young English citizen of Massachusetts colony, farmer and circuit lawyer’s wife, very plainly clothed, to her appearances in public in Paris post-revolution, in French-made dresses whose immodesty at the neck, shoulders, and bustline deeply embarrassed her, to the simpler empire-waisted dresses with modest lace at the decollete which she wore when her husband became the United States’ representative to the court of George III in London, a style which was flattering to her then-plump middle aged body, which she continued to wear as the First Lady to inhabit the incomplete, cold and swampy then hot and malarial President’s Mansion in Washington DC, to her old age back on a farm outside of Boston, where, ever the fiscally conservative housewife, she dressed very simply in American cotton muslins and wools grown, harvested, milled, woven, and made into much more comfortable and simple but serviceable and pretty house dresses, since there was at the time no social standing or benefit connected to being the wife of a man who was merely an ex-president in whom the nation was so little interested that their official portraits as President and First Lady of the U.S. were wrapped in burlap and unceremoniously returned to them via oxcart at their farmhouse from a presidential administration which had no use for them.

I love your terminology posts. Most of all, I think, I love how you trace the terms throughout history, so one gets a clear picture of how not at all clear it is. 😀

Joseph II. Figures. I’m sure he found them wasteful/not economical!

Thank you Hana! It really is true that fashion textile terminology isn’t a fixed thing, and has never been. Just think of how today we can call the same shoe sneakers, trainers, tennis shoes, kicks, etc.

Great post–and great wikipedia wormhole thereafter. For some reason, I couldn’t remember what a mantua looked like. And what is the difference between a mantua and a pet a l’aire? Moar terminology!

Thank you Elise! Yes, doing a post with all the robe/mantuas, what they were called in different countries, and the variants thereof, is definitely on my to-do list.

How interesting, looking forward-as always-to terminology posts. Good luck with all of your projects! Very exciting, and a great break to the day.

So much info! Thanks for sharing your research. I’m glad you’ve jumped on the court gown train because I’m sure your gown will be exquisite and I can’t wait to see you working on it!

On a side note, I follow you on Pinterest and recently I feel like I can sense what you’re working on based on your pinning! I guessed ahead of time the Aniline Dye post, the mention of your working on an elliptical hoop skirt, and your joining in the court gown sew along! 🙂 Just mentioning it because it amuses me.

Best,

Quinn

You’re welcome! I’m pleased to be in on the project. At first I said no, because I have a to-do list for next year, and a court gown wasn’t on it, and then I went and looked at the claimed gowns list a few weeks later, and saw that there were not one but TWO garments that I already have replicas started as UFOs on the list – and neither of them is a robe de cour at all! And then as I finished putting images in this post I was reminded of the image of Mariana Victoria and Louis XV, and the fabric I have, and I couldn’t resist.

Yep, you can definitely see some of what I’m working on on pinterest, though I also have hidden boards, and long-term research project, and curve-balls ;-). I notice what other people are working on from their pins sometimes too.

What an excellent post! Thanks so much for writing it.

I’m also coming across the term “grande robe d’etiquette” in Galerie des Modes, along with snippets from account books for how much they cost (SO MUCH), and I should be posting some … the week after next, I think.

Thank you! I wonder how a grande robe d’etiquette differed from a grande habit (which also cost SO MUCH). I look forward to seeing your blog post.

OMG I MUST see more Regency court gowns like that!

This article is a bit older, but I have been recently reading up on this dress for an illustration project and it was very helpful, thank you so much for this!

In case you still get notifications for this article, I wondered if you know just how formal an event would have to be, to necessitate wearing one. Louis XIV was clearly a fan for grand habit at all times (to be fair, theatre is important business), but was this still true in the mid-18th century? Would ladies wear them from morning to evening before the changes during Louis XVI, if they expected to be in the company of the king? Would they be worn during evening entertainment where the king might appear? I don’t have access to a uni library to check the sources and this is driving me nuts 😀 So if you have any insights you still remember, I’d be very grateful!