As I mentioned in the HSM ‘Out of Your Comfort Zone’ post, my challenge for this challenge is medieval: specifically a gown (kirtle) from the last quarter of the 14th century.

I’ve never made a medieval gown before, and my only dabble in medieval has been a shift (and really, a medieval shift is hardly different from an 18th c shift). So this is a totally new period for me, and definitely out of my comfort zone.

To help, I’ve been relying on the following books:

- Crowfoot, E., Pritchard, F. & Stainland, K. Textiles and Clothing c.1150-c.1450. Great Britain: Boydell Press, 2001

- Thursfield, S. 2001. The Medieval’s Tailor’s Assitant – Making Common Garments 1200-1500. Bedford: Ruth Bean Publishers, 2001

And the following websites:

- Costly Thy Habit

- La Cotte Simple

- Som När Det Begav Sig (no, I can’t read Swedish, but google translate is a wonderful thing)

- Some Clothing of the Middle Ages

- The Battle of Whitsby, 1361-2013

- The Medieval Tailor

And a fair amount of messaging Sarah of A Most Peculiar Mademoiselle (and Som När Begav Sig) and asking ‘is this right?’ in varying levels of panicked-ness.

Though I’ll just get the dress done for this challenge, my medieval journey started over a year ago, when I began researching for fabric, and discovered that medieval appropriate wool is actually really hard to find, at least in NZ (why must all wool fabric be either heavy coating or have lycra!).

With the fabric on hold, I went looking for inspiration:

I love the detailing on Katherine Mortimer, Countess of Warwick’s effigy. I’ll definitely be copying the sleeve length, and the curve over the back of the hand. I’ll see if I have enough energy to do all those buttons (aren’t they amazing though!).

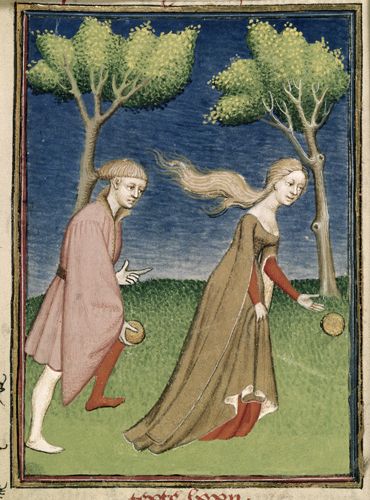

For neckline and silhouette, I really like the overall silhouette and neckline of the red kirtle shown in this manuscript. The neckline isn’t as extreme as many late 14th c necklines.

Also, the dude hanging out in the woods is basically the best thing ever.

I’m not exactly sure what I’m taking from this image, but I love it. Maybe someday I’ll make that overdress… Also, I rather like Atalante as a heroine, especially if she was beating all those men at footraces while wearing those gowns!

I also looked at this image for inspiration, though the neckline doesn’t appeal.

And I like this as a depiction of a slightly more practical, she’s actually doing work in it (though the trailing hem belies any real claims to practicality) garment:

While accumulating inspiration I kept searching for a suitable wool, and I finally found the most gorgeous length of 1960s goose-turd green (yes, that’s an actual medieval colour) wool at Fabric-a-Brac, but it was only 2.8m at 130cm wide. I bought it, but no matter how I measured and manipulated my pattern and thought about piecing, I couldn’t quite get a long sleeved gown out of 2.8m of wool. Wailey wailey!

But, on the WSB fabric-shop-and-afternoon-tea day, I found a midweight, plain tabby weave, slightly felted 70/30 wool-viscose blend in what Pantone would have us call ‘marsala’.

Marsala or not, deep red-brown is an excellent medieval colour for an upper class gown, achieved through either pure madder dye, or madder overdyed with walnut (or vice versa). And I decided that I could live with a wool-viscose blend for my first medieval gown, as the viscose did not significantly change the hand, look, or wear of the fabric.

I’m hoping to use the yellow-green wool for an overgown with short sleeves and tippets.

So, on to pattern drafting in earnest! I had two sewing friends over on a Sunday afternoon, and they carefully followed La Cotte Simple’s curved-front dress draping tutorial, and sewed me into a very snug bust-supportive toile. I was incredibly proud of them, and incredibly impressed with the tutorial, because neither of them had any draping experience, and basically I just stood there and did what I was told!

Except when I was lying on the floor pretending to be an effigy:

Once the pattern was draped on me, I traced it off onto patterning tissue, smoothed it out, and turned it into a full-length pattern:

I’ll have to adjust it slightly once I sew it together, but I’m OK with that. I will be doing all the hidden seams by sewing machine, because I get terrible chillblains in winter, and hand-sewing gets very hard when my fingers and knuckles are all swollen.

At the moment my pattern has 1.5cm seam allowances, which I plan to trim down to 1cm once I feel entirely confident in the pattern.

At the moment my pattern has 1.5cm seam allowances, which I plan to trim down to 1cm once I feel entirely confident in the pattern.

I cut out the main body pieces, and then drew out my four gore pieces, and then had a little panic because my gore pieces only just fit, and there was no fabric left for sleeves!

Oh no! How had I miscalculated?!?

Oh no! How had I miscalculated?!?

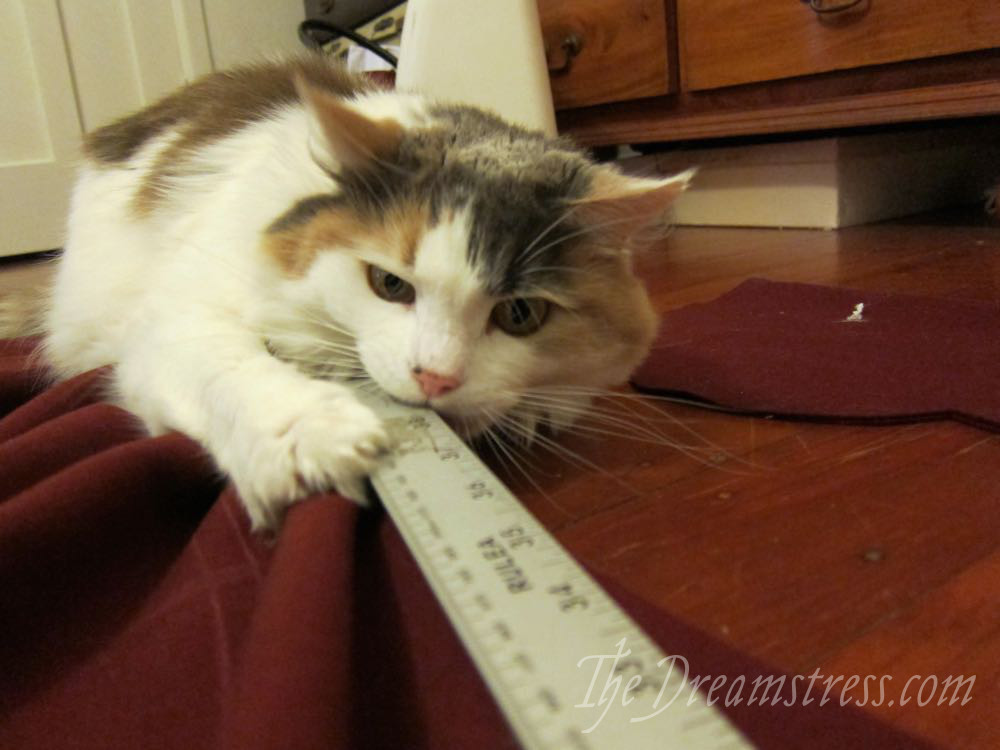

Felicity sympathised, and tried to punish the ruler for me:

Then I realised that I had drafted each gore to take an entire width of 154cm wide fabric, which meant that my finished gown would have a hem circumference of approximately 760cm, which might be just a wee bit excessive…

La Cotte Simple suggests that gores should be at least 61cm wide at the bottom, lest your gown be too narrow, but doesn’t give any further advice. And being me, I started overthinking. If <61 is too narrow, at what point do gores become too wide? What if I’m bigger than the 61cm-is-wide-enough body size?

So Sarah got a message asking what the bottom width of her gores are, or what her average hem circumference is. And she (very, very kindly, and politely) told me to go look at a pattern.

Duh.

So after consulting patterns based on the Greenland finds and the Moy Gown, I have determined that gore widths range from just under the full front-or-back width of a dress, to just over it. Which makes perfect sense, as the full front-or-back width of the dress would have been hugely based/influenced by the available fabric widths, so of course a gore would be a folded fabric width (or two fabric widths with a seam down the centre) as well.

So I re-drew my gores one last time, so that I got all four gores from a folded width of 154cm wide fabric:

(I know, it’s impossible to tell which are the right lines in that mess of lines, but the important thing is that I could!).

Felicity helped:

I’m so glad that Sarah directed me back to the patterns, instead of just telling me a number, because it made me think about the logic of it, and understand the process behind it, which is much better learning than knowing a figure.

With my gores cut, I had all the main body pieces cut out. I’ll be drafting the sleeves later, once the body of the garment is sewn and fitted. (I know, I know, I’m really just procrastinating on the sleeves, because everyone talks about how scary medieval sleeves are, and they have gotten to me and pysched me out, which is dumb, because I don’t find sleeves scary! Usually. I hope!)

Next up: cutting my linen lining, sewing the main body parts together, fitting, and…buttons!

I found this post very educational and entertaining! Best of luck with the rest of the job.

Thank you! I feel like I’m learning so much doing this, and there is definitely a point where all the knowledge comes together and I go ‘ah-ha! I think I kind of basically understand!’. Still so much to learn!

You will be great! These dresses are very beautiful, very graceful, and much helped by posture: so as long as you stand correctly like a willow, it will be just swell.

I imagine (as a pear-shaped person myself), that it will become more flowey, and the gores will become part of the garment, with much use and washing.

Your reference to Pantone cracked me up.

Sorry, I should have said that I am selfish and prejudiced about clothes: What I love is unable to be adored fully because it looks terrible on me. 14th Century and Regency styles are loved but not truly adored. I think that many of use view silhouettes and colors (like marsala–beautiful but ugly on me) through these prisms. I’ve always loved figure-hugging medieval clothing, but gore-placement is terrible. Maybe I am simply being short-sighted, and so I am looking forward to this new piece! Good luck! My aesthetic view depends on you! (Did I say that I was selfish?)

I totally understand. I like things that look good on me because they look good on me, and things that don’t just as much, but slightly wistfully, because it’s exciting to see them on other people, but I still wished they looked good on me!

I can’t say that marsala is my best colour either, but I’ve had such a time looking for a suitable fabric that I would take anything that was the right weight/weave, and a historical colour. I would have preferred a blue, or muted pink, or green, but it will do, and will look good on me with a very white veil and/or wimple. And it is deliciously flow-y, so hopefully the gores will blend in quickly.

I quite like medieval fashion because the body demands are so easy. No boobs? That’s fine, the small bust is fashionable! Boobs are OK too though. Your tummy shows? That’s great, we love it! Let that tummy show! Hips? Yay, we love hips! No hips? No worries, just add more skirt!

Oh yes.

I’m very selfish about Regency clothes. Last Saturday, I wore my Regency dress to theatre (because I can, huh) and my sister went all how great it looked on me – how much of an unexpected silhouette it was, but how great it looked. And I went “Of course, that’s why I’ve loved it for so long, because I knew it would.”

So I’m also selfish about liking that neckline you like here, because it’s very similar to necklines I like for myself.

And I just love your summary of medieval fashion sensibilities above. 🙂

Good luck with the dress!

(Is “marsala” the colour of the Latvian flag, do you think? It’s usually called “maroon”, I think, but it looks suspiciously similar. Because that would be funny because it apparently dates back to the Middle Ages, that flag.)

Oh how lovely! Ok, so you will just have to enjoy your Regency dress double-times for me, deal?

Deal! It’s become hot and I’m not prepared for it and the dress will come in handy. 😉

That is very true: the general medieval style is pretty generous to various body types. Glad that I am not the only one who wishes everything looked swell on one’s own body–but can be happy when other people are thrilled (if still wistful).

Felicity is definitely a Plus compared to other sewer’s pictures… (did you ever sew something for her ? I sewed a collar for for mine, and tried some cat-nooks).

I totally agree to what Elise said. I like very much some period gowns, but know that they won’t fit me (or I will look like a meringue). I like very much when sometimes I can see pictures of old dresses that were made for round woman (Queen Victoria for example), because I wonder how they survived their period costumes (for example in the 1900, when most of what you could see was made for filiform girls, with no breast or hips). It’s rare to see but very interesting.

Haha! I wonder how many people would stop reading the blog if there were no Felicity

Sewing for Felicity is definitely a no-go. We used to buy her collars, but she figured out how to take them off. And she’d pretty much rip your arm off if you tried to put actual clothes on her!

I’d be quite interested in tips on the period accurate way to finish the neckline and front lacing area if you had any of those!

What a pretty piece of wool! I do adore this dress and this period, and I love seeing how other people tackle it …

I’ve been reading, if not commenting, for a while, and it’s pretty obvious that you’re interested in the philosophy behind the various garments you reconstruct. But I’ve been making medieval garments for a long time, and I think the philosophical underpinnings are different enough that they’re worth thinking about….

1. Fabric is handmade. Thus expensive, thus rare. Using fabric for a pattern or a toile is like buying a car to use as the pattern for a second car. It’s much cheaper, even taking into account the cost of an expert’s time, to redraw the pattern on this piece of fabric, each time. (Paper as we understand it is largely non-existent and not terribly available, even if you can afford it.)

2. Because of 1., patterns are much likelier to be “recipes” or proportional. There is a tailor’s pattern book from the 1500s but I don’t believe that it was intended to be used in the way we use a paper pattern. Recipes may be well known and passed around; it’s hard to say.

3. The vast majority of garments are made individually. Modern ideas of appropriate ease are inextricably tied up with the problems of ready-to-wear, that is, making a garment for a standard size, rather than a particular individual. Yes, there may be any amount of ease, but it vares across periods and according to individual taste.

We can see in the surviving art that the cotehardie or kirtle was very flattering, and its enduring popularity leads me to believe that it was also comfortable. But based on my own experiments, and what I’ve seen of other reconstructions, if you approach the kirtle as a “standard” garment according to a “standard” pattern, you will be disappointed and quite possibly end up with something that is neither comfortable or flattering.

I have, based on my own experiments, a number of tips for making this dress, which I am happy to share. But for now I’ll stop, and not take up your whole comment page!

So pleased that you’ve started commenting! Especially with such interesting, thoughtful things to say. I am always, always OK with massively long comments – I like it best when the comments section becomes a real conversation with give and take and learning. 😀

I think we’re very much on the same page, just looking at it from different angle: I’ve definitely thought of all of those things (just not in quite as organised a way), and of course, the vast majority of them also hold true for periods that I am very familiar with, like the 18th century. Fabric was still terrifically expensive, and clothes were still made specifically for the person.

And I was also trained to drape garments before I drafted patterns, and then to draft patterns, both predominantly for the theatre and dance, where you are draping and drafting for specific bodies, and only then did I really start using commercial patterns. I do tend to think about garments and fit as a recipe, and that I approach sewing much more like a historical seamstress than a modern Big-4-using sewer, or a commercial garment pattern-maker.

While it doesn’t look like it, because the process is so different, the way I chose to go about creating this dress was actually hugely informed by thoughts of how expensive fabric would have been, and how garments would have been created. Here is my thought process:

I knew I was not, especially for this dress, going to be able to make it in a way that mimicked how a medieval gown would have been created. Unlike a medieval seamstress, I’ve never seen a well-made (i.e. reasonably historically accurate) kirtle in person: I live in the wrong part of the world for that. I’ve certainly not been trained by period seamstresses/tailors, and been able to watch and help before I attempted one myself. My entire process is based on books and websites, which is (of course) not remotely how a medieval sewer would make a garment. The garment and pattern would be a new field for me, and, since I couldn’t drape it on myself, I was going to have to rely on friends who have not only no medieval experience, but no draping experience.

Many experienced modern medieval seamstresses advocate using the linen that will be the underlining for the final gown to drape the gown template. However, from Costly thy Habit and La Cotte Simple’s demonstrations, this is hugely wasteful of linen: and linen is expensive, especially since I want to use a really good, stable, vintage linen for my support lining. Between the waste, and knowing that my drapers might not get it right the first time, I couldn’t risk using the actual fabric for my lining. So I used an old, stained linen. While not period accurate in practice, it did mean that my usage of the final, pricey, linen, would be minimal, and I felt this was more accurate in spirit.

I turned my draping into a pattern simply so that it couldn’t stretch and warp with use and over time: I know it’s not accurate to have a ‘pattern’, but I won’t be in a situation where I have people to help me drape and fit the dress as I make it, or for future gowns, so having a template will allow me to cut a gown without excess fabric in the future – and, once again, I felt this was more accurate in spirit. The pattern is doing what a tailor would do for me as a client, if you will!

I’m also thinking of the pattern as a template, or (as you say) a proportional receipt: it’s going to create a garment that fits well enough for me to fit it on myself. It will end up being different for every garment and fabric, but it will allow me to cut knowing that there will be minimal fabric wastage as I adjust, which is what would happen if I could drape every garment on me.

Having made one, if I were now to make a medieval dress for a friend, I would be able to use a method that is much closer to what was probably used in-period: working with panels that were just over 1/4 of the body measure, draping them on, fitting and basting, and cutting the dress straight from that.

So, I know I followed a very un-period process, but I did it with period constraints in mind!

And the end result of the cutting is not too un-period in fact. Both my actual wool and actual linen will be used to almost un-useable scraps (any wool bigger than a 1″ square is becoming a button). 😉

Hi again! Well, I haven’t said much before now, because honestly I’m not familiar with anything much past 1500. Once there’s a waist seam, I get bored and drift away. 😉 So I look at your posts and admire them and enjoy them but all I could say would be — wow, that’s pretty! Although I did show the Dazzle information to a non-sewer, who enjoyed it enormously.

Anyway. But I do know a little bit about cotehardies, and unfortunately one of the things I know is that there is a lot of “bad” information out there. What I mean by “bad” is this: it produces a garment that the seamstress doesn’t like, that doesn’t fit her, and that ultimately she doesn’t wear. I’ve repaired or remade a few of them. And I just hate to see people fail at big projects because of bad advice.

For me, one of the most essential tricks to the cotehardie is getting your head straight before you start. Now that you’ve spelled out some of your thinking, I’m embarrassed that I was worried about you. 😉 I’ve just spent so much time trying to explain, even to Regency and Victorian re-enactors, the parameters of the medieval world, that it’s almost automatic.

For example, I know that there were a lot of changes in fabric production technology between 1500 and 1900 (to pick dates at random), but I’m not as familiar with them, and I don’t always know when they become applicable. So for example the spinning jenny, which really gets going around 1780 and is replaced by 1820 by the much better spinning mule, eliminates most of the labor involved in hand-spinning and reduces the cost of fabric. So fabric is steadily dropping in price, but of course modern mills are, well, modern. So I didn’t know how much of a factor that might be in your thinking.

I came at the cotehardie from the other end of history, in a lot of ways, and learned a lot of the background as I went along, in order to understand what I was seeing. So I am really excited to see your results, since you have started from clear on the other side of the project.

To wrap this up — I also use a body block for a rough cut, because, well, fabric IS cheaper than assistants, for me as well! I draft it from measurements onto a piece of tightwoven cotton and use it for the first cut of the liner, then go on from there with draping and fitting. Fabric stretch is so important; I once had to cut a dress off of the model, because I had badly misunderstood how much linen would stretch — and how much cotton would NOT stretch!

(I once reduced a six yard length of stuff to a bliaut and a snack size ziploc baggie of scraps, thread, and fluff. I hope I never have to cut that close again!)

But all of this conversation has inspired me to start writing up what I know about cotehardies and maybe I’ll even put it up on the web one of these days.

I agree! I really do appreciate your long and thoughtful comment. So glad you wrote!

Medieval sleeves make a lot more sense to me then modern ones, so don’t be scared of them 🙂 Just look at a lot of paintings of sleeves and sleeve set ins, there are a few that are quite detailed. And just try to make a mock-up of fabric that looks and behaves a lot like your wool. If you put them toghether once it makes a lot more sense.

I also learned from Hadewych Hillegenbacker (not online) to put a body of antique linnen inside the dress, because antique linnen was woven more tightly it doesn’t really stretch, so that way the bust support shape is maintained even with a lot of wear.

Your dress is such a nice color, and seeing this really motivates me to stitch away again on mine ^^

It’s great to see you tackling medieval gowns. I’m trying out a first 14th century gown too, and using a light merino/viscose blend with a twilled weave. The colour is a bit brighter than your beautifully muted one (deep pink), but I’m hoping to get away with it!

You’ll probably think me very lazy, but I used a Simplicity medieval costume pattern sleeve for my dress. It’s out of print now, and the rest of the dress (especially the skirt) is hit and miss in its authenticity – but the sleeves are spot-on, and take a lot of the guesswork out of the matter.

Have you seen this blog https://katafalk.wordpress.com/ ? She’s a medieval reenactor and history student in Sweden I think. But the things she does with wool are AMAZING. Also she makes fabric buttons look simple and elegant. 😛

Oh. Em. Gee. What an incredible site!

Oh yes, very familiar. She does amazing stuff! You’ll see her site turn up on my reference list once I start blogging the sewing and finishing details, and accessories – she’s much more focused on that than the pattern drafting and research of period shapes and silhouettes, so wasn’t so useful at this end of the project.

The last time I made a 14th C gown the internet barely existed and internet with pictures wasn’t really a thing yet. There is so so much more information out there now to go and learn. It will be interesting to see how your gown turns out.

I have made some of these dresses before, and have never had problems with sleeves. I have used both the fit-bodice-before-cutting (ala A Cotte Simple) and fit-bodice-after-cutting (ala The Medieval Tailor) methods but always with the sleeve-directions from Costly Thy Habit, and always with great results. You are not lazy for not having cut your sleeves, as they are best made after a final fitting of the bodice. You can do this, I believe in you 😀

pinterest.compinterest.compinterest.compinterest.comThose sleeves are pretty amazing. I can’t wait to see the finished dress! Eeeeee!

The front of the dress has laces, does anyone know if lacing on sleeves was done in medieval times? I can’t find anything about it. I just love hand-sewn eyelets, I’m dreaming of making something with them. They are probably time-consuming, but the technique looks cool on sleeves.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/399624166904711087/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/491455378056775764/