Every once in a while when I post a purple 18th century dress on Instagram someone comments in surprise that they didn’t think there were purple fabrics in the 18th century.

The fame of mauvine, and the story of the first aniline dye, means that people sometimes think that it was so exciting because it was the first purple dye. Not at all! All shades of purple were already wildly popular in the years just before Perkin’s found mauvine, because Queen Victoria had chosen to wear purple at her oldest daughter’s wedding in January 1858, and lilac was fashion trendsetter Empress Eugenie’s favourite colour.

Mauvine was exciting because it was a shade that was incredibly hard to dye with natural dyes, and was cheaper and faster than natural alternatives.

There were indeed natural alternatives, and purple fabrics were absolutely available before 1859, and in the 18th century.

Here’s a quick survey of extant garments, paintings, and fashion plates from the second half of the 18th century showing purple garments, as well as some fabric samples. I’ve arranged them chronologically. Together they give some idea of the shades of purple available, and types of garments that came in purple.

Purple wasn’t the most common colour in century: almost all purples available at the time were relatively tricky to dye, relatively expensive, and prone to fading and colour change. Over time they could turn brown, blue, pink, or grey as the dye faded or underwent a chemical change.

Purple dye’s tendency to be fugitive means there are less extant 18th century garments in purple. It also means that we can’t be certain that the shade of purple we see today is the same shade the fabric was when it was first woven. However, the combination of paintings showing purple garments, and extant purple garments, gives a good idea of the range of purples available in the 18th century.

The 1760s:

We don’t know who this lady is, or exactly where she lived, but the details of her dress and hair place her in the 1750s, and we know she’s most likely English. Her dress, cap bow, and ribbons are all of matching purple. Note the little picot edging on her purple ribbons and neck ribbon, and the pins holding her sheer fichu at neck and bust. The artist was paying attention to all of the details of her dress.

Unknown lady, English, ca. 1750

The 1760s:

This dress was probably less brown when new:

Robe à la française, c.1760, Denmark, Violet and pink iridescent silk brocade. Museum at FIT.

Robe à la française, c.1760, Denmark, Violet and pink iridescent silk brocade. Museum at FIT.

There isn’t much information available on this bodice, but the style of fabric suggests its an Turkish silk, made somewhere in the Ottoman Empire:

Corset, back view, 1760-1780, Centre de Documentació i Museu Tèxtil

Interestingly, this portrait of Mrs Jerathmael Bowers shows her in Turkish inspired dress. Was purple particularly associated with the Ottoman Empire? They were certainly master weavers and dyers. Was purple one of their specialities? This dress, however, must be taken with a grain of salt. Copely copied the portrait, down to every detail of the dress, dog, tree, clouds and rose, from a mezzotint of Joshua Reynold’s portrait of Lady Caroline Spencer (née Russell), Duchess of Marlborough. The dress in the original painting was blue, but Copely would certainly have tried to pick a plausible colour, to make his fakery as realistic as possible.

Mrs Jerathmael Bowers, 1763, John Singleton Copley (1738-1815)

Here’s a Francaise in a darker purple from the second half of the 1760s, although the fabric may be slightly earlier:

Sack and petticoat, purple silk, brocaded with flowers and lace, French, 1765-1770. Victoria and Albert Museum, T.708&A-1913.

The 1770s:

And another one, this time in a silk that’s more typical of 1770:

This fabric is between pink and purple but I thought it was worth including:

Robe a la Francaise, Italian, about 1775, Silk taffeta brocaded with silk and metallic threads, MFA Boston, 77.6a-b

If that doesn’t quite qualify as purple for you, the dress in this charming miniature unequivocally qualifies:

Miniature, late 1770s

And for another shade of purple in a portrait, here is Elizabeth Hervey and her very lavender ribbons.

Elizabeth Hervey, Marchioness of Bristol (1778-1779). Anton von Maron (Austrian, 1733-1808). Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum

Here’s another one that’s quite tricky, especially as different images of this garment show different shades. If the first image is correct, this is a shade that was sometimes called ‘garnet’.

A shot mauve-grey silk gown, late 1770s. with boned, low pointed back panels and internal skirt loops, sold by Kerry Taylor Auctions

A shot mauve-grey silk gown, late 1770s. with boned, low pointed back panels and internal skirt loops, sold by Kerry Taylor Auctions

Fashion plates aren’t the most reliable sources for garment colours, as the colourists could choose their own combinations (as demonstrated by the two differently coloured fashion plates of a lady at her toilette), but the colours do match up with what we see in extant garments and portraits. They also presumably reflect what was seen as fashionable, tasteful, and correct in la modé.

Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Francais. “Femme en Caraco plissé de taffetas changeant gorge de pigeon..” 1778, MFA Boston

Femme galante à sa toilette ployant un billet. French, 1778. Designed by Pierre-Thomas LeClerc, MFA Boston

Femme galante à sa toilette ployant un billet. French, 1778, Designed by Pierre-Thomas LeClerc, MFA Boston

Purple also appears as touches of colour in prints. This mainly pink dress has purple flowers:

Overdress of a robe à l’anglaise, Chintz: painted and resist-dyed cotton tabby, English dress made of Indian export chintz, c.1780, Royal Ontario Museum, 972.202.12

Read more about it in this Rate the Dress.

Overdress of a robe à l’anglaise, Chintz: painted and resist-dyed cotton tabby, English dress made of Indian export chintz, c.1780, Royal Ontario Museum, 972.202.12

The 1780s:

Here purple appears as lilac flowers on a hand-painted silk gown, which was also the focus of a Rate the Dress:

Robe à la Polonaise (actually a Robe à l’anglaise retrousee), ca. 1780, French, silk, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.146a, b

Here’s another example of a very pinky purple as painted by Vigee-Lebrun:

Elisabeth Louise Vigee-Lebrun, self-portrait with a straw hat, after 1782

And the same artist’s take on a dark purple dress:

Élisabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun (French, 1755 – 1842) The Vicomtesse de Vaudreuil, 1785, Oil on panel 83.2 × 64.8 cm (32 3:4 × 25 1:2 in.), 85.PB.443 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

As well as dark garnet, and lavender combined in one garment:

Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français, Plate 208

And a jacket in purple and blue stripes, and petticoat in garnet and lilac:

Galerie des Modes, 46e Cahier, 5e Figure, 1785

On the theme of purple stripes, this late 18th century jacket from the Met’s collection has bold ombre stripes in green and violet:

This embroidered panel was never sewn up into a jacket, which means the purple group is quite unfaded.

Vigée Le Brun seems particularly fond of painting subjects in purple. Was it more fashionable amongst the French?

Élisabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun (French, 1755 – 1842) The Vicomtesse de Vaudreuil, 1785, Oil on panel 83.2 × 64.8 cm (32 3:4 × 25 1:2 in.), 85.PB.443 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

This fashion plate, discussed in this 2019 Rate the Dress post, shows a nearly identical fabric, identified in the caption as violet taffeta.

Redingote of violet taffeta, revers, collar, and cuffs white, steel buttons, striped and spotted muslin petticoat- puce straw hat trimmed with large steel buckles- it is edged and belted with black velvet. 1787

This matelasse (learn about the fabric here) jacket is also French in origin, and shows another example of purple verging on brown.

Caraco en toile imprimee matelassee, 1770-1790, Museon Arlaten

But Catherine the Great takes us back to bright lilac, in the shade that Eugenie would later favour:

Portrait of Empress Catherine II of Russia, Fyodor Rokotov after Roslin 1780s, Hermitage

Purple Fabrics:

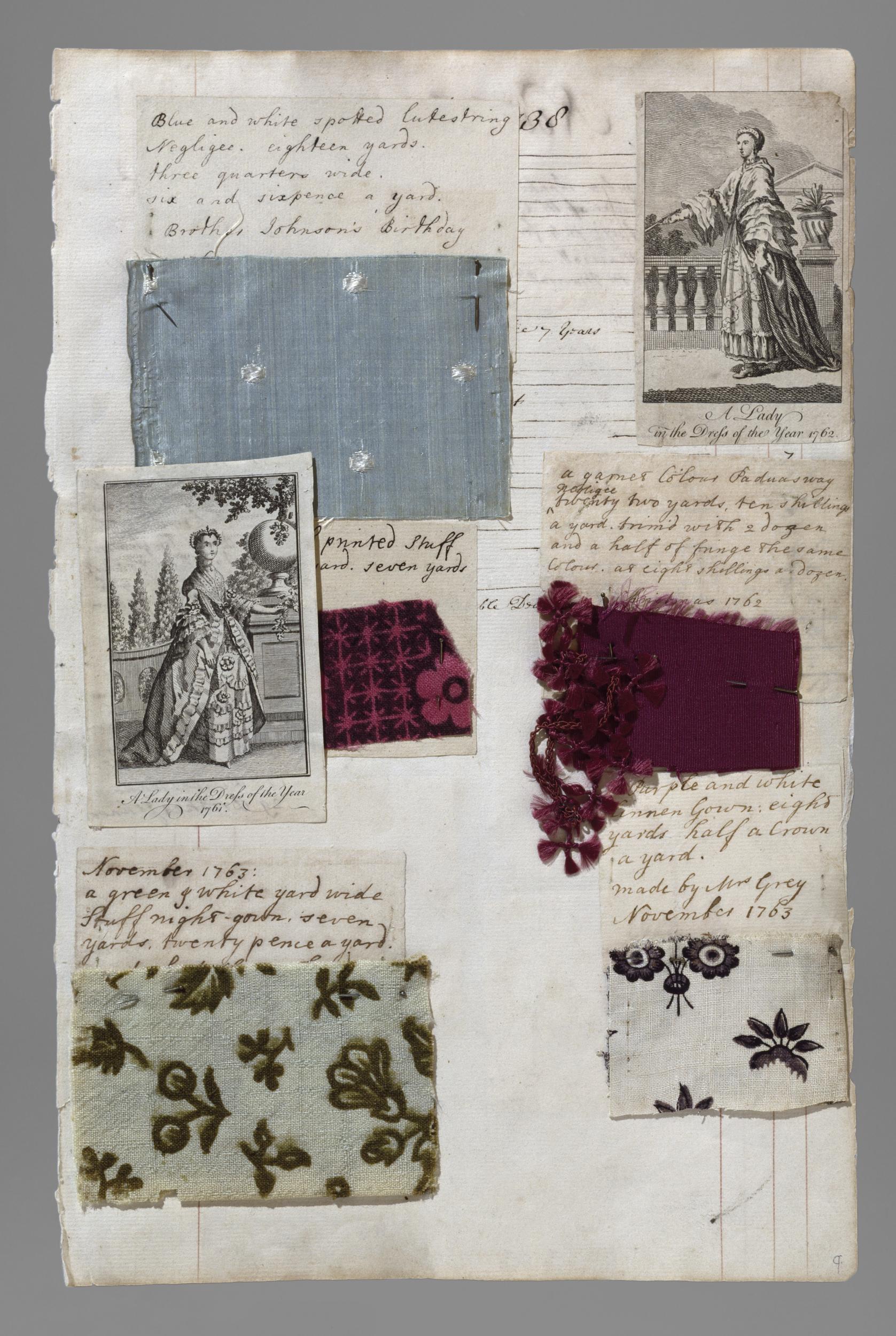

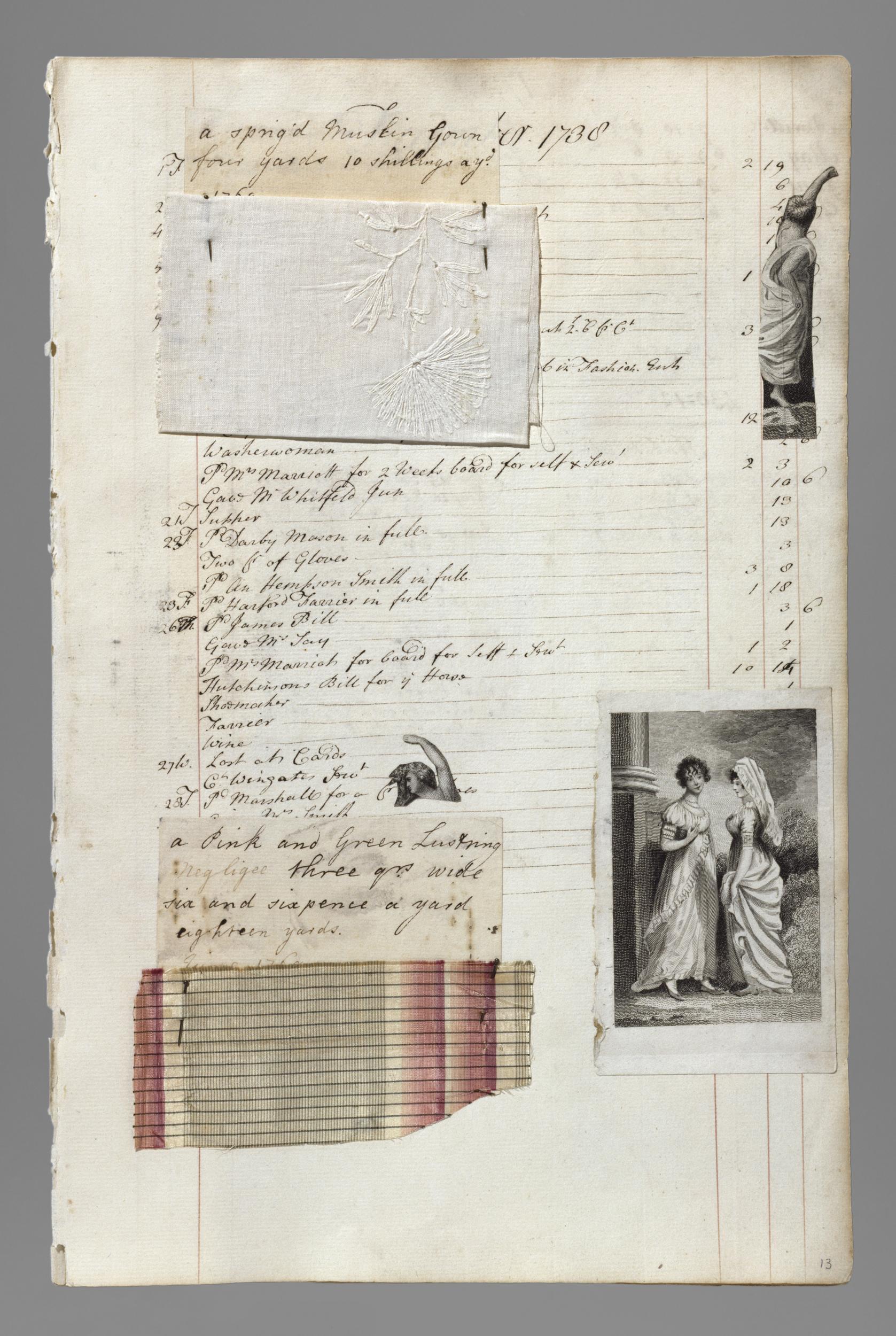

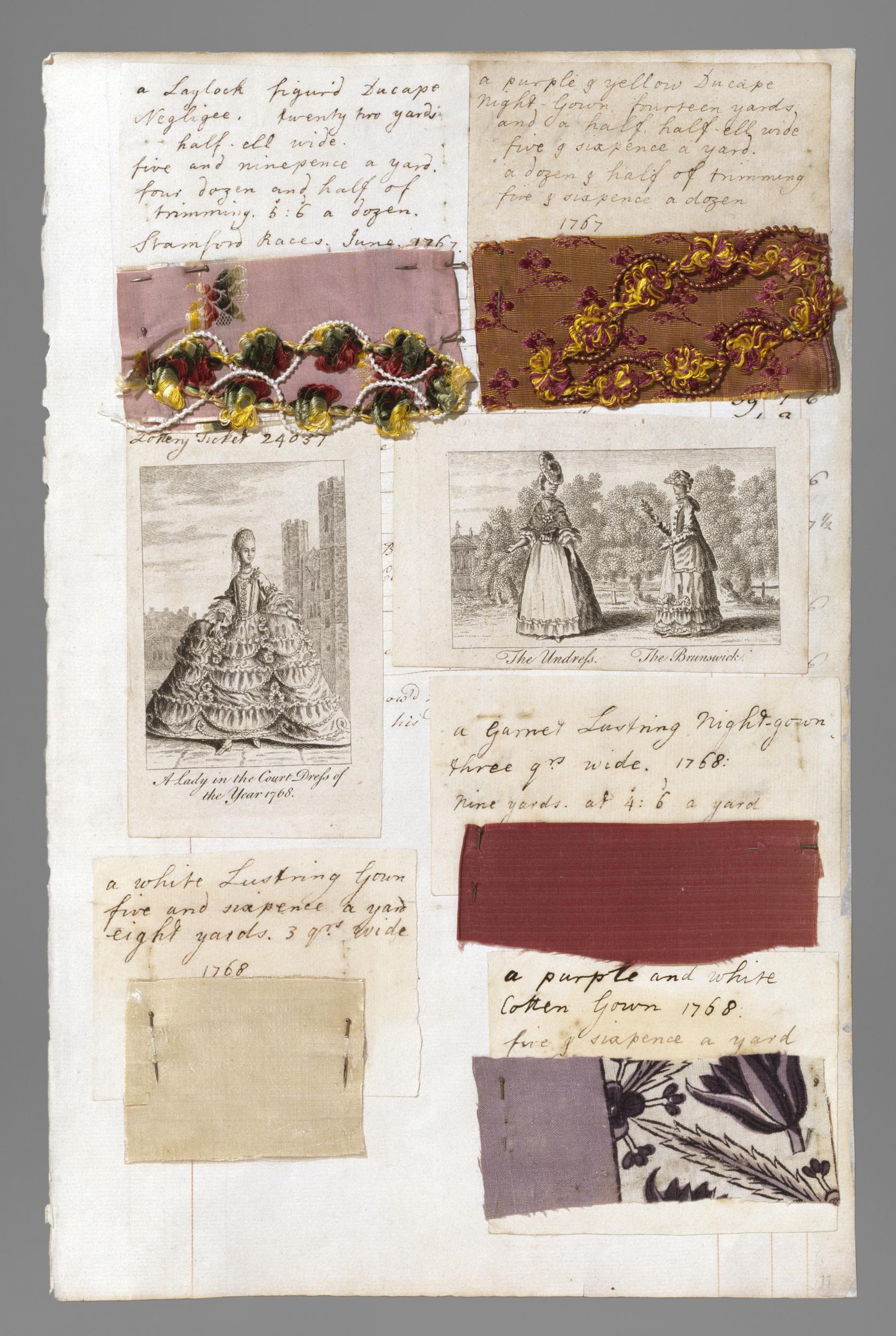

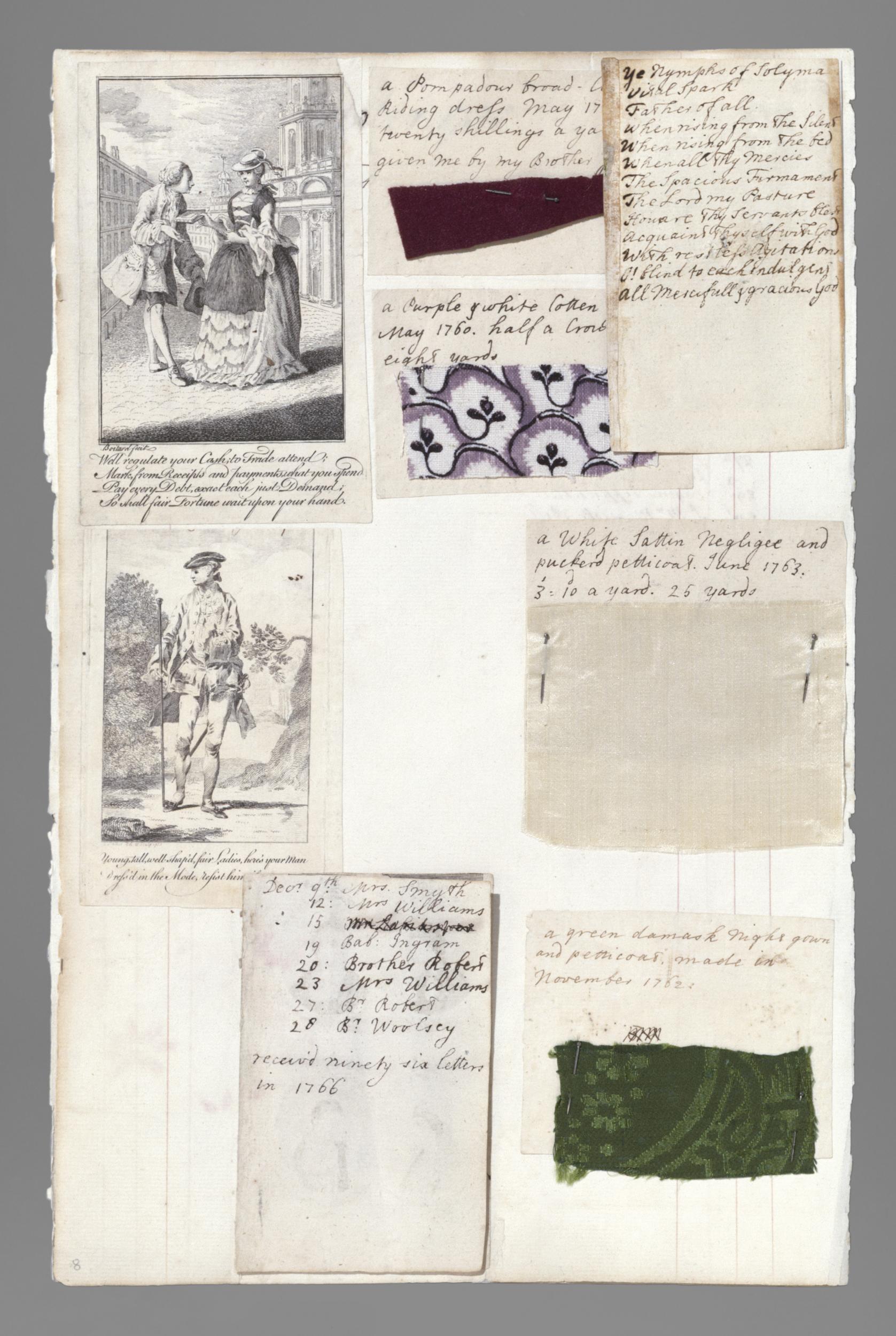

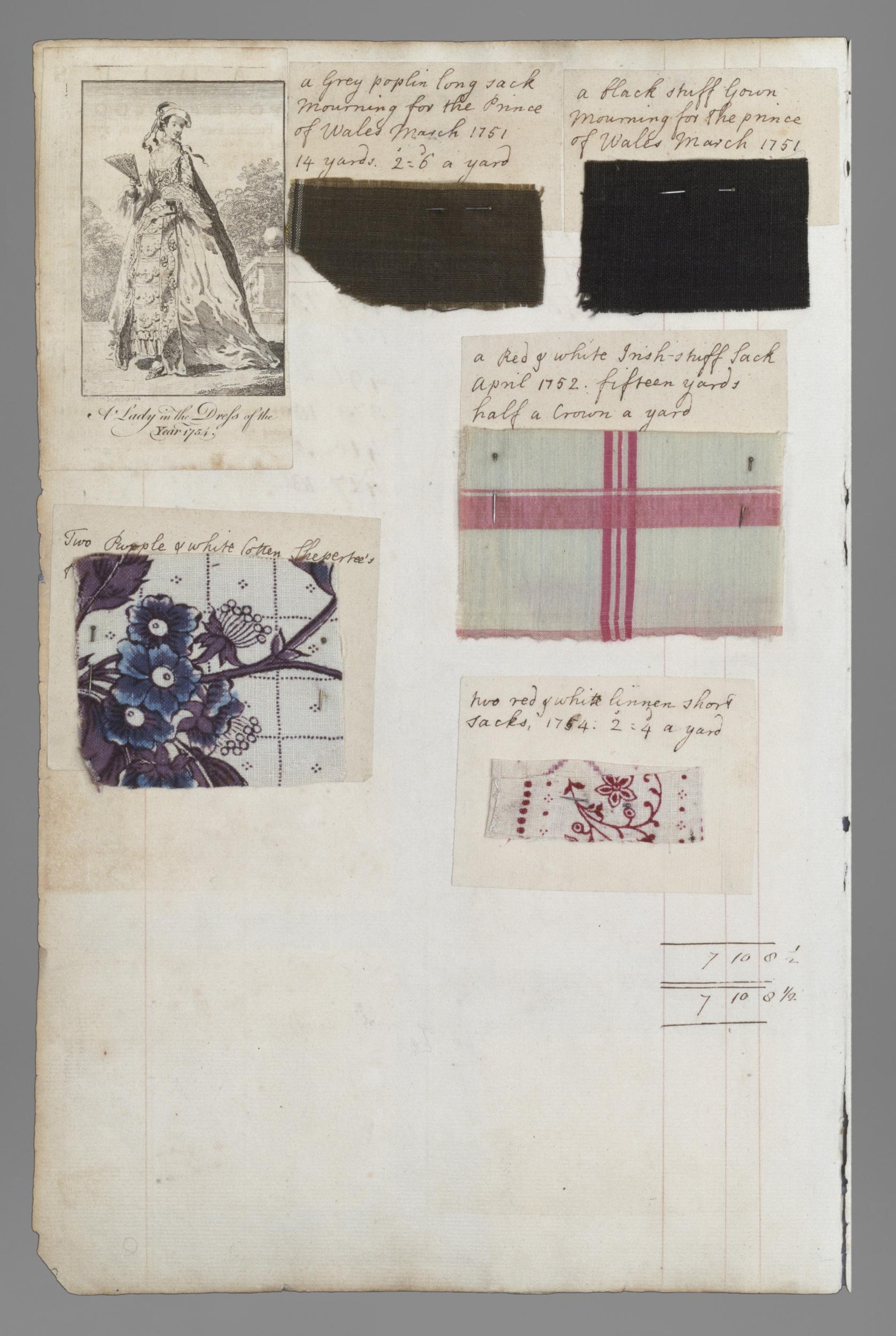

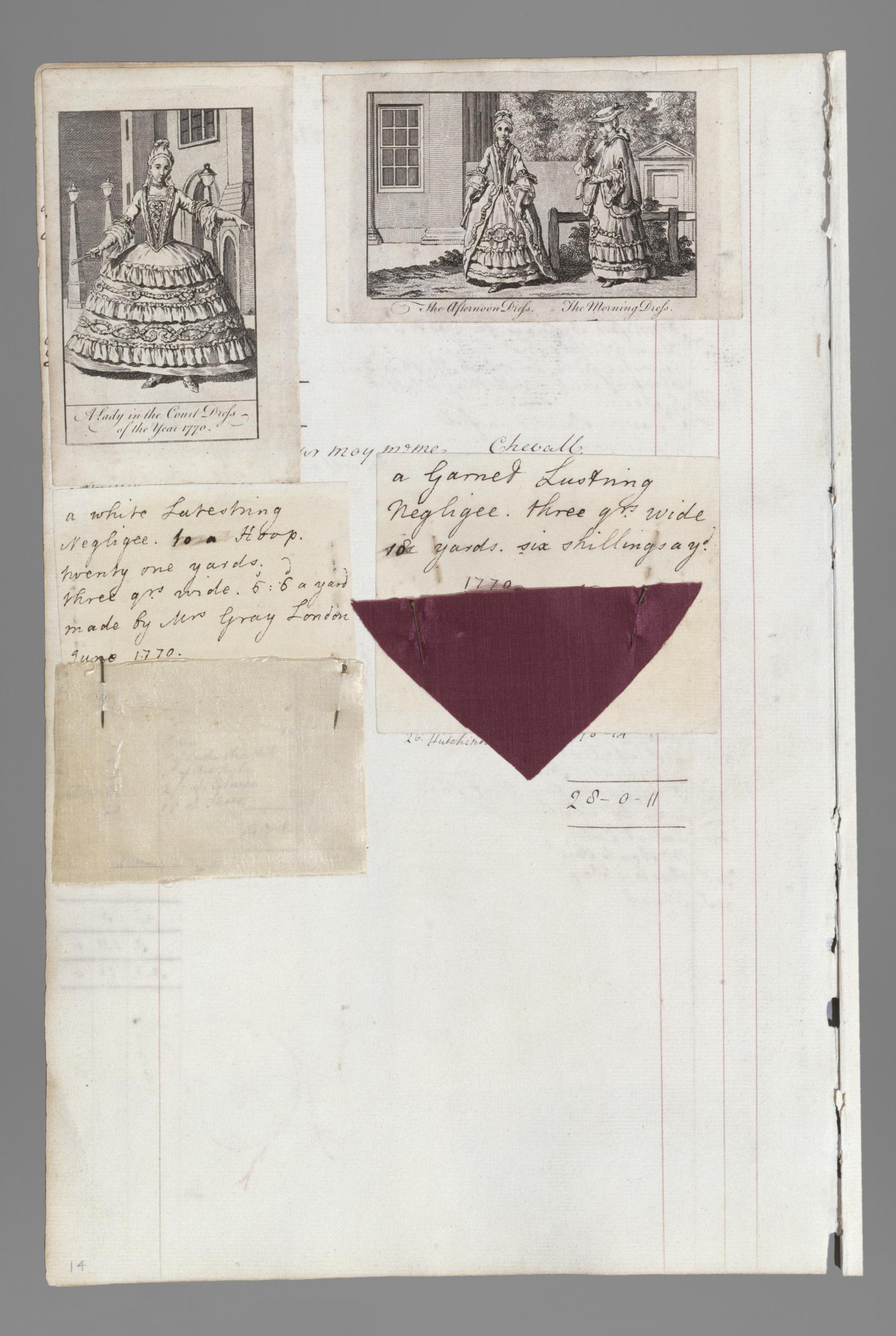

I’ll finish off with a selection of pages from Barbara Johnson’s fantastic album of fashion plates and fabric samples.

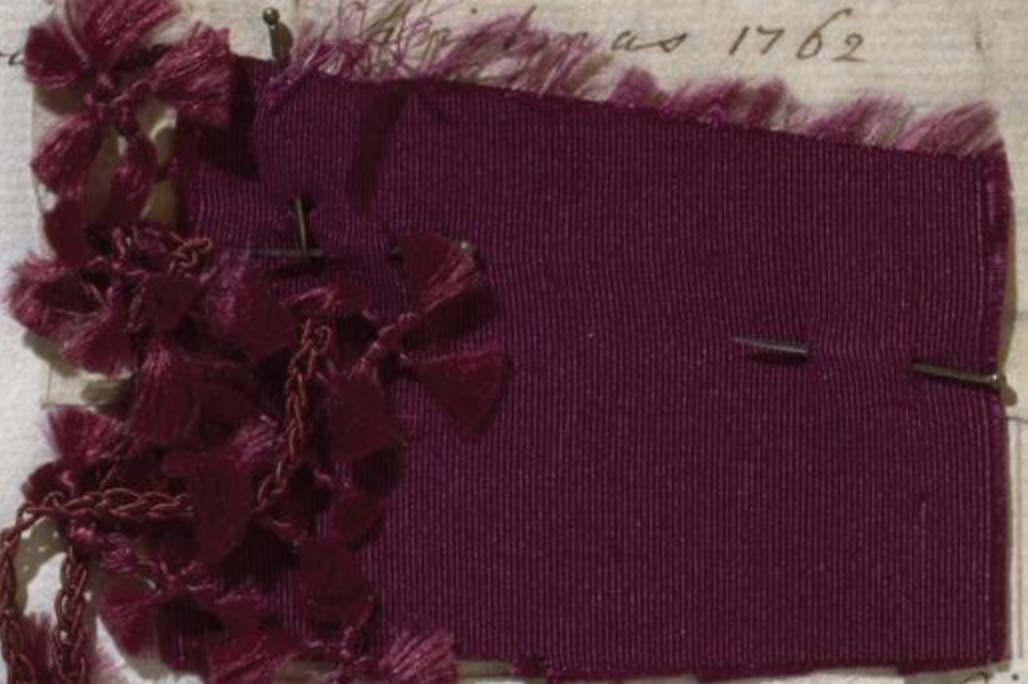

A garnet paduasoy and matching fringe from 1762, as well as a printed stuff (a worsted wool) in similar hues:

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

Johnson calls this striped lustring ‘pink’, but I’d call it purple:

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

The figured silk in the upper left corner is also quite pink, but the smaller floral in the upper right is definitely described as ‘purple and yellow’, and the cotton in the lower right is also identified as purple:

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

The broadcloth for a riding dress is called Pompadour, which, at least in some decades, was used for purple shades. There’s also another delightful purple and white cotton print from 1760.

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

And an utterly charming floral over shepherds check:

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

And finally, a lutestring in the red-purple called garnet:

Barbara Johnson Album, England, 1746-1823, Paper, parchment, textiles, Victoria & Albert T.219-1973

Great post! Thank you:)

Thank you for a really fascinating compilation!

What a wonderful collection! I’ve once attended a lecture on purple fabric and dyes in antiquity which was fascinating. Most were dyed with Royal purple, made from sea snails, and their harvesting is incredibly laborious. Wikipedia tells me (when I had to look up the English name of the snails: Murex unfortunately, in both German and French they’re called purple snails which is just marvelous) that the best manufacturing came from the Levant, even in antiquity. That’s why the pigment is also called Tyrian purple (from Tyre). They commented that the loss of the Levant to the Arabs really disrupted the Roman/Byzantine purple dyes. (Although clearly Byzantium recovered, since purple stayed the imperial color). I think this might be a reason why purple fabrics might, in modern times, be associated with the Ottomans who controlled the middle east.

I also vaguely remember reading that plant dyes that also produce purple work better on plant fabrics. Is that true? That might create a distinction between expensive, ‘Oriental’ purple silk and more mundane purple cotton, dyed with orchil lichen or woad+Kermes.

purple being one of my favourite colours, i really enjoyed seeing this post. 🙂 and i have so much love for the striped purple and green jacket above, and especially for its ombre effect trim.

i have experimented with plant based dyes, and purple is indeed definitely achievable, although it tends more toward mauves and pale lavenders unless using an overdye/double bath technique. with indigo or woad blues plus cochineal/kermis (or safflower?) reds, you can get all sorts of things. there were some gorgeous purples in use in asian textiles quite far back… fastness, of course, is another issue, as you pointed out. the reds, blues, and purples derived from marine snails were, apparently colourfast, such as the famed “tyrian” purple–aka “phoenician red”, and made by people on crete even earlier as well.

one quirky facet of studying colour or textile history is that there is so much overlap between colour words used to mean hues that we call quite distinct things; red and purple being one of the prime examples. “purple” in classical references seems to have meant things we would likely call red or crimson or magenta, at least at times. then we have the convention of calling scarlet hunting coats ‘pink’ to this day…

and aren’t we lucky that the barbara johnson album survived? such a fascinating resource for its period.

Wow, that lady with the striped petticoat (Galerie des Modes, 46e Cahier, 5e Figure, 1785) looks like she lives a very interesting life!

I know right! I kinda want that dress now!

Is Catherine the Great wearing purple hair powder?

Possibly! Coloured hair powder was a thing in the 18th c, though I’m not sure it came in purple. It may just be the tint of the photograph.

What a wonderful post and I loved Barbara Johnson’s album. Her illustrations were torn from the ladies diaries of the time.

I used to be a dyer and tried dyeing with lichens as we had lots blown down in the storms when we lived in Wales, I achieved a mauve but never a dark purple with them. I only did this once, I got my husband to pee in a large sweet jar that was full of lichens, this was put in the poly tunnel in the heat until it went purple. You can imagine why I only did it once! This got lots of laughs when I did talks to women’s groups. I only dyed sheeps fleece with it. I still have a sample 30 years on. The idea came from the fact that in the Shetland Islands and Scotland wool was dyed this way for Harris Tweed type fabric, but also for dresses which apparently gradually faded to lots of shades of mauve.

That’s really interesting. And amusing!

This is very interesting. I think, that natural dyes/ techniques pre-1850 are super relevant for contemporary fashion and an expertise in this field is really valuable. I don’t know about the historical trading connections but I could imagine that Africa must have an interesting history of fabric dyes and techniques, that maybe wasn’t as well known to the European market as those from Silk-Road-countries such as China and India. That’s what I‘d suppose, but I’ve got no idea.

I really like the corset made of Turkish silk

(Centre de Documentació i Museu Tèxtil) and the embroidered panels for a man’s suit (Metropolitan Museum). I must say Elisabeth Vigee Lebrun was really fashion forward for 1782 and her purple Chemise a la reine is lovely. And those pages with swatches and fashion bits and pieces from the Barbara Johnson Album are adorable.

This is exactly the best kind of Dreamstress post: A look at a particular color, thread, material, or other salient feature. This is so interesting. Thank you so much!

Thank you! I love writing this kind of post, but they take so long! It took me almost 5 hours. I’m going to try to do more though!

Very interesting. I knew purple dye was available long ago (bible mentions a woman who sold purple cloth) but there’s always lots too learn.

It would be so neat to see all of these as they were when new! I absolutely love the garnet dress. I just recently came across that picture and ! Those pleats! Swoon!

Some of the most famous purple robes were those worn by caesars and senators in ancient Rome, the dye coming from a type of sea snail. An early example of a restricted/sumptuary color.

We love color and will find it, however exotic or rare the source.