I’m extremely excited to be showing you a fully done, properly photographed, newly sewn historical outfit. It seems so long since that has happened!

Too long…

This outfit was also a long time coming. It was on my list as a wardrobe hopeful for my Fortnight in 1916 experiment, based on fashion advice articles which extolled the virtues of jumper dresses over skirts and blouses, as a wool jumper frock was more durable, and could be worn for many more days than a cotton blouse without needing washing.

I based my own ever-so-practical jumper frock on this page from The Pictoral Review Monthly Fashion Book, Dec 1915:

I loved the double-button detail, and the asymmetrical crossover bodice, both so typical of the mid 1910s. It just seemed to period-perfect, but also so classic.

I loved the double-button detail, and the asymmetrical crossover bodice, both so typical of the mid 1910s. It just seemed to period-perfect, but also so classic.

I also liked the severity, especially with the grey, black & white colour scheme, though the palette on these pages is so limited that it’s not the best indication of what colours the frocks would be made up in. I’m quite certain the ridiculous historicism laced-bodice number at the back was not meant to be grey!

I got the skirt part of the dress cut out and started before my Fortnight in 1916, but stashed it in the PHD pile when it became clear that I didn’t have enough prep time to make it before the experiment started, and I didn’t need to to have a complete wardrobe.

For my dress, I used the same gorgeous Tasmanian merino wool twill that I used for my Bluebell trousers (and which I still think Lynne gave me!). It looks grey in real life, but comes up very purple in photos.

Last May, while doing more research, I noticed that the pattern for my inspiration dress also appeared in the January 1916 edition of the Pictoral Review, only in black, with red touches and hidden buttons:

I really liked that this print showed it with a hat and muff, confirm it could be worn out.

(can we take a moment to swoon over the ridiculous-fabulous hat worn with the brown checked dress?)

My started dress came out in the run-up to Costume College, and with a lot of help from wonderful Wellington friends like Nina of SmashtheStash & Zara of Off-Grid Chic who came and spent a day helping me sew, and wonderful new Costume College friends like Carolyn of The Modern Mantua Maker who literally sat in a class and sewed buttons for me.

(a moment of silence and awe for how awesome these people are and how lucky I am!).

I got the dress done enough to wear at Costume College, but I wasn’t 100% happy with it. The front of the skirt was hanging slightly oddly, and the seam allowances around the armscyes weren’t finished.

So, after Costume College I did a bit of unpicking and re-jigging and got the dress just right, as a late Historical Sew Monthly July ‘Fashion Plate’ challenge, and just in time for the Sew Weekly ‘Make this Look’ challenge.

Then Mr D & I went and had fun taking photographs at the Sir Truby King gardens. We happened to be there on a house open day, but there were no volunteers around, so we didn’t go in, but he got some good photographs right in front of the house.

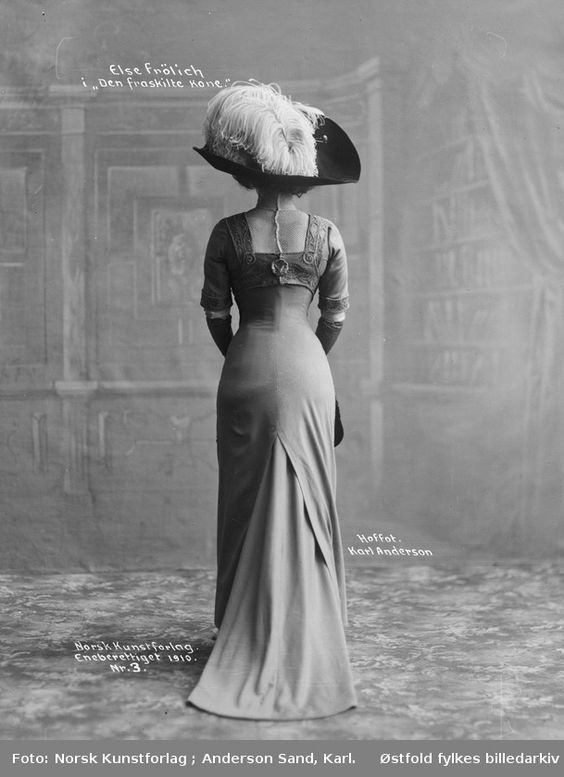

We only got one good photograph of the back of the dress, with the interesting collar detail that was a happy intentional accident – I split the mock-up collar to work out what to add to the curve to make it look right, and we (the amazing sewing crew) liked it so much that I incorporated that into the final collar.

In many of these photographs I’m carrying a white camellia: the symbol of the women’s suffrage movement in New Zealand.

By 1915, New Zealand women had had the vote for 22 years, but were still fighting for the right to be elected for office.

The white camellia is still a relevant symbol, because we’re still fighting for equality: a major new study has shown that sexism (not time taken for maternal leave, women’s over-representation in poorly paid industries, etc, etc.) is the main cause of the pay gap between men and women in NZ (we make 84cents to the $ in the same jobs).

Overall I’m very happy with this make. The bodice is a tiny bit long in back, and maybe a tiny, tiny bit fuller than it ought to be, but generally I really like it.

I’ll do a follow-up post next week with construction details. For now, here is the Historical Sew Monthly info:

What the item is: a 1915-16 day dress based on a Pictoral Review illustration.

The Challenge: #7 Fashion plate

Fabric/Materials: 3-4m of grey-purple Tasmanian merino wool twill (a gift), 1m of white cotton voile for the under-bodice (probably about $5), scraps of black linen (thrifted, $2 for enough to make a 1910s blouse and the collar and cuffs here, so .20cents!)

Pattern: Based on 1910s magazines, sewing books and patterns in my collection.

Year: 1915-16

Notions: cotton thread, buttons, hooks and eyes and snap fasteners,

How historically accurate is it? Quite good, though I’m not 100% convinced I got the waistband application correct.

Hours to complete: 9 of mine, another 9 from friends (have I mentioned how amazing they were?_

First worn: Costume College, Sat 29 July — not quite finished, and then again last weekend for the photoshoot.