Silk ribbon adds the perfect finish touch to lots of historical garments, from bows on the front of the Amalia Jacket, to ribbons on 18th century caps, to jabots for the Selina Blouse.

But silk ribbon is expensive, not many places carry it, and sometimes you need an exact colour or weight that’s simply not available.

I solve this by making my own. It means I can have ribbon in any colour and weight I can find fabric in. It’s really affordable too. 1m of 120cm wide $30pm fabric makes 24 meters of 2”/5cm wide ribbon. $1.25pm of silk ribbon? Not bad!

(plus, you know, thread, and labour… And I’ve never actually turned an entire meter of fabric into ribbon. But the concept is sound! And most fabrics, even silk, are less than $30pm, even in NZ.)

The way I make silk ribbon uses a sewing machine. It results in a finish with a slightly stiffer edge along the sides of your ribbon: a bit like the woven edge of real silk ribbon.

I like that this technique looks more like ‘bought’ ribbon (which most women would have been using historically), and is more durable than hand-hemmed silk.

Is machined hemmed ribbon that looks and behaves more like woven-edged ribbon produced on a loom more or less historically accurate than hand hemmed silk? I guess that’s up to how you think about it.

So on to the technique!

You’ll need:

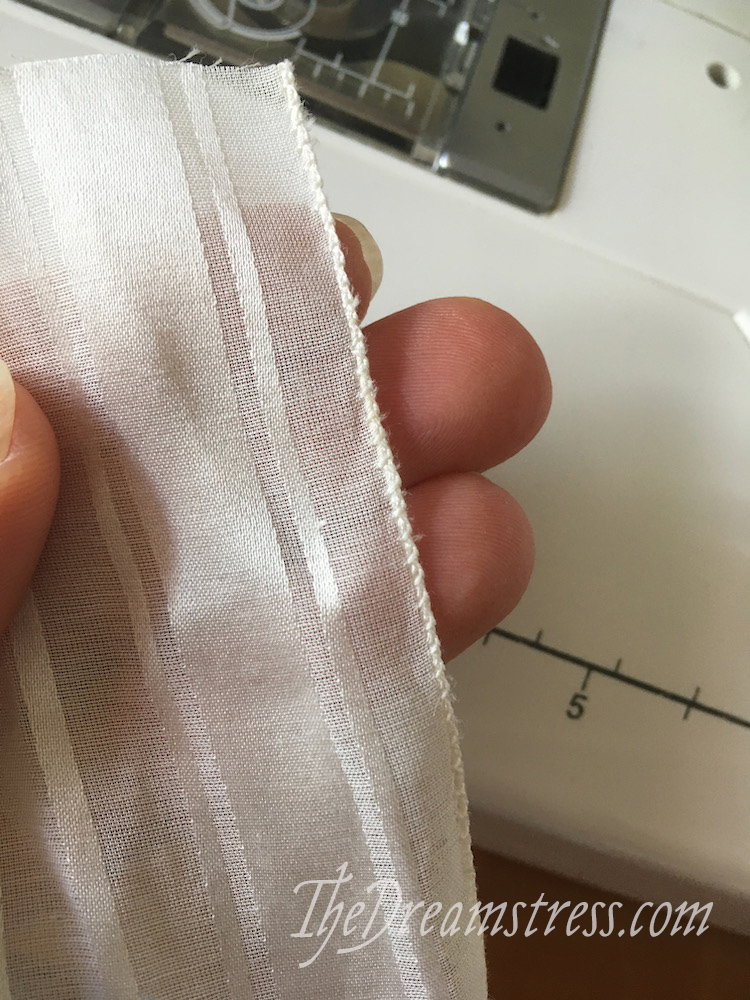

- Light-midweight silk fabric (taffeta, charmeuse and other light satin weaves work well) cut into strips 1/8”/3mm wider than you want your finished ribbon to be.

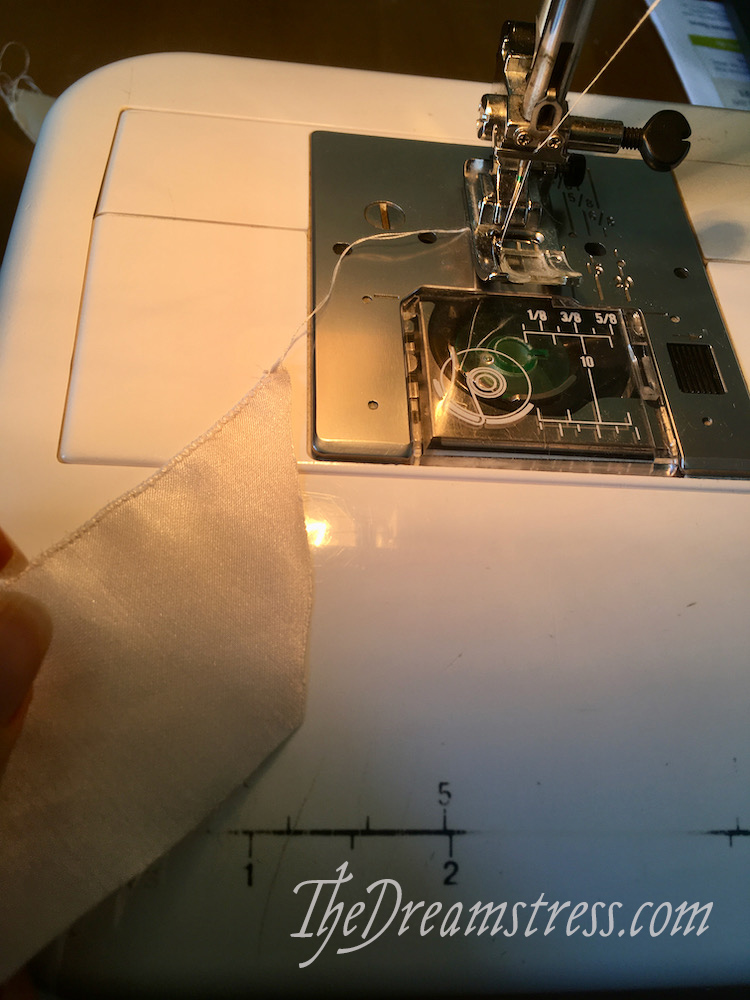

- A sewing machine set to a zig-zag stitch with a moderately high stitch width, and a very narrow stitch length.

To make the ribbon:

Zig zag along the long edges of your silk strips, allowing the needle to fall just off the edge of the fabric on one edge, so the zig-zag stitch wraps over the raw edges, and folds in the edge slightly.

If you want the ends of your ribbon to be finished, leave tails of thread at the end of your stitching, to help you pull the ribbon through the machine when you start on the next corner. Then knot off the hanging threads to finish each corner.

Tips:

- Always test your zig-zag stitch on scraps of your fabric, to make sure you like how wide and dense it is.

- Experiment with cutting your fabric along the length, or across the length: you’ll get different drape and curl to your ribbon each way. I usually prefer fabric cut across the length, with a selvedge at each short end of ribbon.

And that’s it!

Use your ribbon to decorate dresses, trim hats, tie up your hair, etc, etc.