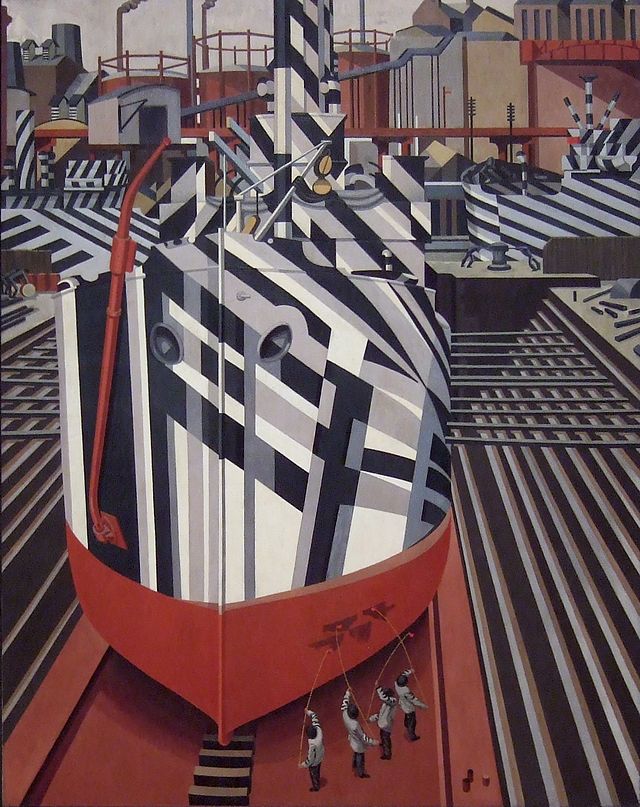

‘Dazzle‘ (or ‘Razzle-Dazzle, or Dazzle Camouflage) was an early use of camouflage in modern warfare. It looked like this:

RMS Olympic (sister ship of the RMS Titanic) in dazzle camouflage while in service as a troopship during the Great War.

And this:

Starting in WWI, Allied ships, and, less frequently, airplanes, canons and tents, were painted in a series of broken stripes and intersecting geometric shapes – not to hide an object, but to confuse, or ‘dazzle’ the eyes of observers. The point was not to conceal a ship, but to make it hard to tell precisely what kind of ship it was, where a ship was, which direction it was going in, and how fast it was travelling.

The goal of Dazzle, as the British Admiralty explained was:

…to make it look as if your stern was where your head ought to be.

If you think that a Dazzle painted ship looks like a cubist artwork, you’re absolutely right. The concept of Dazzle is generally credited to artist Norman Wilkinson (though zooologist John Graham Kerr had earlier proposed a disruption system inspired by animal camouflage). He knew that steamships could not be hidden because of the trail of smoke they left, so he thought of a system which was designed

…not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading.

Most World War I era Dazzle patterns were designed by modern artists, some of whom documented the ships in striking geometric paintings. On seeing a be-Dazzled cannon Pablo Picasso claimed Cubists had ‘invented’ Dazzle, but both influencing the other throughout the war and in the decades that followed (Dazzle was also used on some ships in World War II). Artists pushed themselves to create patterns for ships the further de-constructed the ships shape, and artists looking at Dazzled items attempted to apply the same de-construction to non-military items.

In a world of khaki, rationing (yes, there was rationing during WWI in many countries), and dye shortages, the Dazzle ships, painted in a myriad of bright colours, were a novel and appealing sight. They immediately caught the imagination of the patriotic but novelty and colour-starved public – and fashion designers.

Dazzle’s popularity was immediately reflected in fashion, though more extravagant interpretations had to wait until war was over, and curfews and rationing ended.

Interestingly there were three completely different ways in which ‘Dazzle’ was interpreted in fashion. A Feb 1920 London fashion column describes the first:

“The coming season will reveal the most dazzling frocks which London has ever seen” they didn’t mean that designers were producing ensembles in shiny fabrics, shimmering in sequins and dripping glittering jewels. This, however, was not at all what the columnist meant. Instead “dresses will have the queer, fantastic effect of the patchwork quilts of our grandmothers days, for they will be a jumble of startling colours.” The article goes on to explain that “the completed dress will rather resemble the highly decorated ‘dazzle’ ships which sailed our shores in war-time.”

This appliqued velvet dress by Natalia Goncharova for Mybor shows a bit of this type of Dazzle inspiration (filtered through Goncharova’s own take on Cubism).

Evening dress of multi-coloured silk and velvet applique on red silk. Designed by Natalia Goncharova for Maison Mybor, Paris, about 1923, V&A

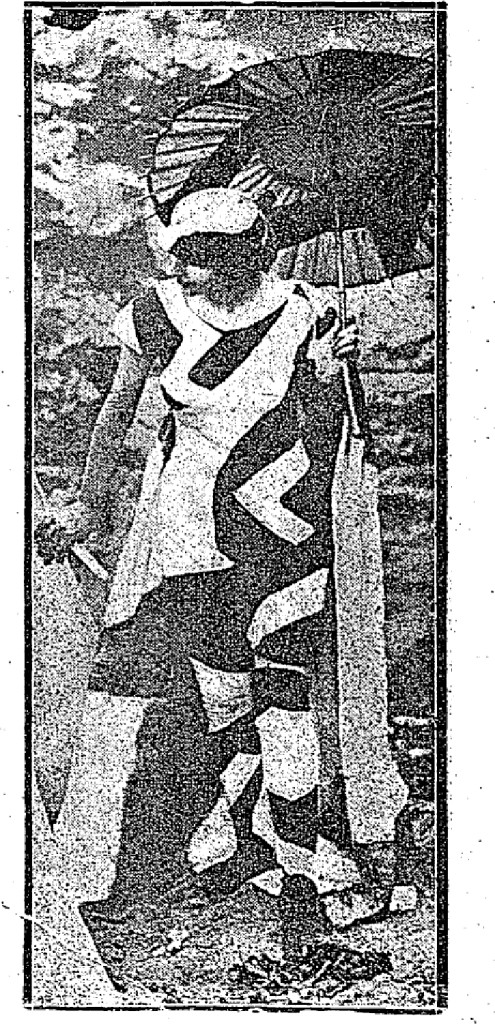

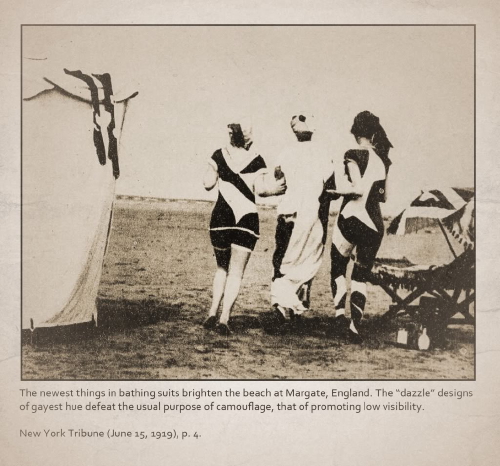

This type of dazzle was also seen on swimwear on beaches around the world in 1918 and 1919, with fashionistas who donned the vivid suits wittily claiming that it did not matter how scant their swimwear because:

No one will notice my bathing suit / after it has made them notice me.

As the Washington Herald described it:

Camouflage, according to the general understanding, is intended to conceal, but the young lady who sprung a “camouflage” bathing suit at Coney Island this afternoon–providing that was her intention–failed to accomplish any such purpose.

It is doubtful if anything about the suit, or the young lady, escaped the attention of the several thousand persons on the beach. No two could be found who agreed on the details of the costume, but they all agreed beautifully regarding the details of the young lady.

The second way in which dazzle influenced fashion was in a fad for bold checks and stripes in the late ‘teens and early ’20s. These appeared mainly in sports and casual wear, often combined in vivid, clashing, improbably colour combinations. Fashion columns of 1919 describe ‘dazzle’ waistcoats with “loud checks and stripes” often paired with matching stockings.

Finally, on a more subdued note, dazzle brought in a trend towards monochromatic black and white garments (which were previously rarely seen except for mourning).

Dazzle ships were usually brightly coloured, but the black and white photographs of them shown around the world led people to assume (as some still do) that the patterns were monochrome, not brilliant, contributing to a fad for black and white.

Phillips, C. Coles. (illus). Calling Costume from la Maison Week. The Crowell Publishing Company. 1916

The black and white trend was particularly popular because fabric dyes were also in short supply during WWI. Germany had been the world’s biggest supplier of fabric dye prior to the war, leaving the Allied powers with significant shortages during the war. Britain had also been an important dye manufacturer, but manufacturing priority was given to the war effort, and the chemicals used in dyes were wanted for weapons manufacture. By 1916 dyes were already in short supply, so subdued colours and monochromatic schemes were considered patriotic, and were widely shown in fashion magazines. Dazzle fit in perfectly with this.

Black and white dazzle fashions were originally in bold stripes and geometric patterns, but quickly becoming more subdued, and resulting in the classic black ‘poet suit’ with white collar and cuffs, and the timeless ‘little black dress.’

There was one particularly dazzling offshoot of Dazzle: ‘Dazzle’ themed balls, with black and white decorations and geometric fancy dress, were all the rage between 1919 and 1921, the most famous one being the Chelsea Arts Ball in 1919.

In the Southern Hemisphere, a Dazzle ball was held in Nelson in 1919, and there were ‘Dazzle’ performances at other NZ balls and concerts. The concept was so popular it appeared in plays as well. A Dazzle fancy dress ball held in Melbourne in 1920 received widespread coverage in New Zealand newspapers – though much of it was quite disproving, with tsking over ‘forced and unwholesome gaiety’ and comments on scant skirts and bare backs, chidings people “whose taste (or lack of it) inspires them to make an extremely liberal display of shoulders.”

Despite its popularity and its use both in WWI, and WWII, there were no studies done to test whether Dazzle camouflage was actually effective. There was a great array of designs, and the different designs were never tested and analyzed to see which worked best, so we still don’t know if it worked at all for its intended purpose.

It was definitely quite effective, however, as a method of sparking public interest, and boosting spirits during wartime, as well as a fashion inspiration. The Dazzle trend died out fairly soon after the war, but reappeared under the name of Jazz Stripes, or Jazz colours.