Fashion is often criticised for being frivolous, pointless and superficial: existing for no purpose, and being driven by nothing but the whims of people with too much time on their hands.

People who say this couldn’t be more wrong. Fashion is one of the truest indicators of the state of society, and as you trace the history of fashion, you see all of the events which changed the world are reflected in changes in clothes, and sometimes changes in clothes change the world.

Wars interrupt trade, and lead to changes in the availability of dyes and fibres, which show up in clothes. Trade routes out of the American South were blockaded during the American Civil War, and Europe and the Norther US had trouble sourcing cotton fabric. The South, in turn, had trouble sourcing silk and luxury items like buttons. Not quite a century later, World War II would cause so much unrest and destruction in the Far East that a number of varieties of silkworms went extinct, and certain silks can no longer be manufactured.

Wars can also foster trade. The various Crusades exposed Northern Europeans to the luxury fabrics of the Middle East, both those imported from China along the Silk Road, and those produced in Constantinople. What they saw, they wanted, and a trade in satins and velvets North from the Byzantine and Ottoman empires through Venice made the city rich and powerful, and forever altered Northern European fashions.

Portrait of the Venecian Doge Francesco Foscari, ca. 1457—1460 or mid to late 1470s, Lazzaro Bastiani (1430—1512), Museo Civico Correr, Venice

Natural disasters like earthquakes and major storms wipe out industries and destroy technology. The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 hugely affected the Southern European textile industries, contributing to the rise of cotton as an acceptable textile for everyday wear, and the dominance of Northern European textile manufacturing throughout the Industrial Revolution.

Natural disasters often lead to pestilence and epidemics, which have their own effects. A drought in Kashmir in the 1870s led to widespread famine, which turned into epidemics of disease. By the mid 1880s, it’s estimated that 70% of the weavers in Kashmir were dead, taking with them the Kashmiri shawl industry, and a garment that had been the epitome of luxury in Western fashion for almost a century.

Political alliances led to exchanges of materials and trends. The marriage of Catherine of Aragon to Henry VII saw the introduction of the farthingale into England in the 16th century, paving the way for the classic stiff Tudor and Elizabethan silhouettes.

Catherine Parr in a skirt supported by farthingales, by Master John, 1545, National Portrait Gallery, London

Fashion has also affected politics and world events in its own right.

Wars have been fought to gain control of fabric and fashion. Much of the English conquest of India was driven by a desire to control the flow of Indian cotton fabrics into the West (and tea, but fabric was a huge part of it).

Wars have also been stopped, or at least paused, for fashion. During the 18th century ‘little ambassadors’ or dressed fashion dolls were routinely allowed to cross borders during conflicts where all other goods were stopped.

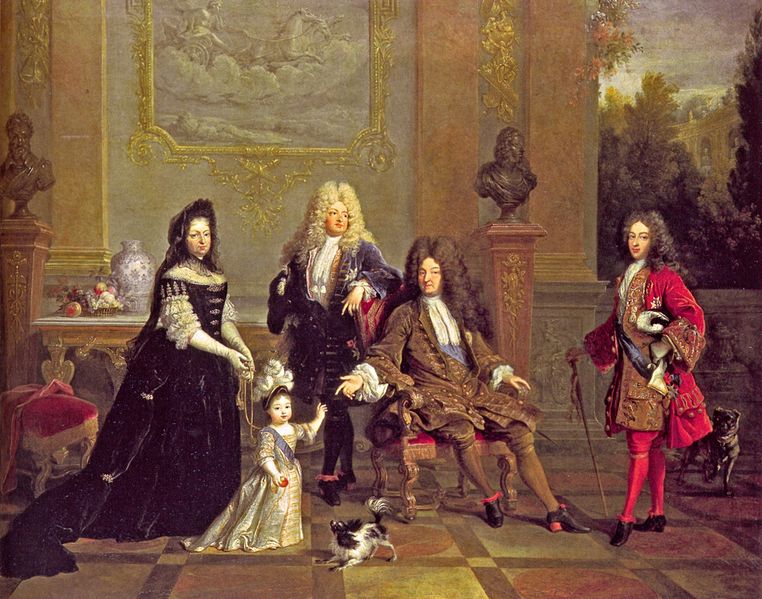

And nations have even engineered their entire foreign policy around fashion. Louis XIV of France set out to make France the most important nation in Europe by making it the leader in style and fashion. He created a uniform of court clothes (the robe de cour and justacorps) that became the proscribed court wear across most of Europe for a century and a quarter. At points he almost directly bribed Charles II to make the ensemble the prescribed outfit at the English court, thus spreading France’s influence, and selling France’s silks. The Sun King even want as far as to have mirror-makers and weavers kidnapped and brought to France in order to ensure that France would have the best mirrors, and could make the most beautiful fabrics.

Louis XIV and heirs with the royal governess, Formerly attributed to Nicolas de Largillière, now unknown, circa 1710

In the HSF Challenge #11, The Politics of Fashion, due Sunday 15 June, the challengers are asked to create an item that illustrates the intersection between politics and fashion. I’ve given a few ideas, but these are just a fraction of the ways in which clothes have changed and been changed by world history.

As with the Innovations challenge, this challenge may require some research, which obviously I think is fantastic. I can’t wait to see all of the beautiful creations, and to see all the ways in which we have found links between the way governments and nations were shaped and changed, and fashions were shaped and changed!