A lot of people are astonished when the hear that I sew entire 18th century garments by hand, and mention that they find handsewing hard and intimidating. Here are 5 quick tricks to make it a lot easier – whether you are hand-sewing your own elaborate historical garment, or just sewing on a button or mending a tiny seam.

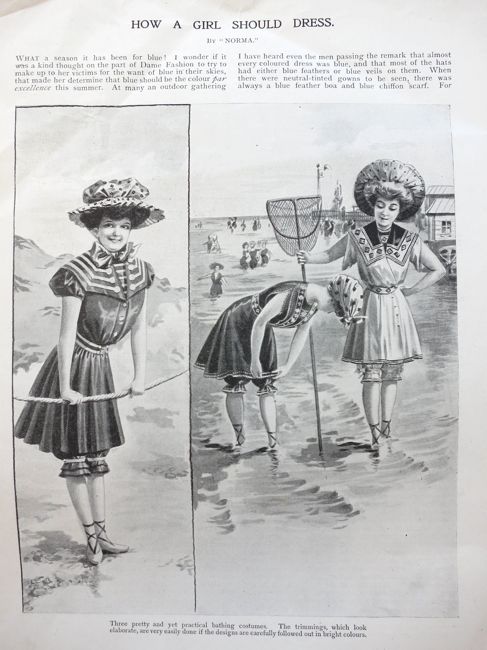

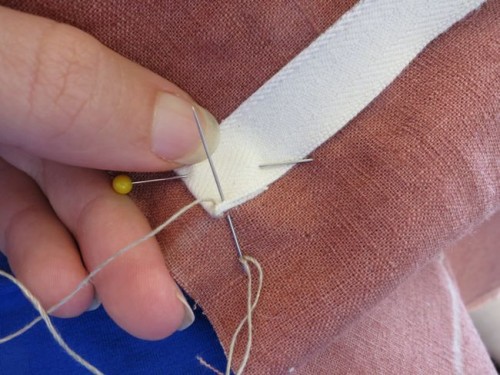

Hand sewing on the hoop channels on my paniers

1. Use good needles (and the right kind).

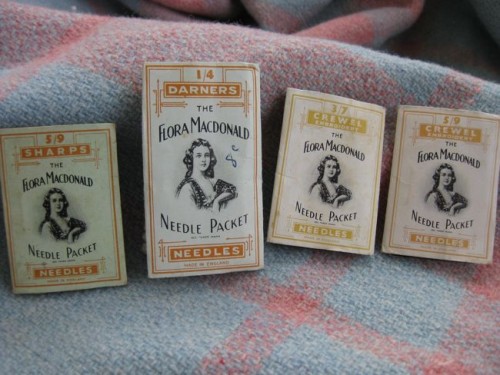

There are different qualities of needles, and different types of needles, and it’s important to have the best quality needles you can afford, and to use the right type the type of sewing and the type of thread you are using.

Yes, a packet of good, high-quality needles can cost you up to $9, whereas the bargain store have them for $1, but the last time a student brought in bargain needles to a class of mine we ended up tossing the whole packet because they were all blunt (really blunt. The tip of each was FLAT). You may spend more money initially to buy really good needles, but if you take care of them, they will last much longer, and save you money on needles, fabric, and thread in the long run. I have a whole stash of beautiful, high quality vintage needles thanks to Nana, but for modern needles J James are great, and Mrs C raves about Piecemakers.

Different types of vintage Flora McDonald needles

A needle with a blunt or snagged tip will catch on your fabric, causing pulls, and it will take you more effort to push it through the fabric. A needle with a ragged or too-small eye will wear and cut at your thread, causing it to fray and break – costing you time, money, and finish on your sewing. Good needles will save you so much time and effort when sewing, and will be much better for your fabric and thread.

Use a needle that has an eye just big enough to comfortably hold your thread, without it having to squash through the hole, or without a lot of slipping. A finer, thinner needle will slide through fabric more easily – so generally the finer the better as long as it isn’t squashing the thread. Get a threader if you have trouble threading the needle.

Needles do come labeled with their recommended use, but I use that more as a guide than a rule.

2. Use good thread (and the right kind).

A good quality thread will make a huge difference in the ease and durability of hand sewing. A poor quality thread will be fuzzy and prone to knotting, breakage and fraying as you sew with it, and more likely to break when the item is worn and used.

When handsewing (and machine sewing) I use like for like threads: cotton for cotton, linen for linen, silk or fine polyester for silk, polyester for synthetics (though I rarely hand sew synthetics, or hand sew with synthetic thread), and cotton for wool (though I have use strands of wool thread pulled from the fabric itself for some wool sewing, such as my pallas and stola).

The type of thread will affect the weight of the thread, but there are also different weights within types of thread: finer for basic sewing, heavy twist for extra strong sewing and buttons.

Different weights of vintage thread

As I have discussed before, I regularly use vintage thread, and find that as long as it was good quality thread to start with, it works every bit as well as new thread of the same quality and type. For modern threads, I like Gutterman and Mettler threads equally. Coats and Clark I find quite inferior.

A selection of beautiful vintage threads

3. Wax your thread.

Waxing smoothes down the fluff of your thread, and glosses over the twist, helping it to slide through the fabric more easily. It also keeps the thread from kinking and knotting. It’s particularly important when working with linen and cotton threads.

My bee patterned beeswax

A cake of wax is very cheap (mine was $3.50) and can last for decades. As an added bonus, mine is pretty, and smells like honey, so just picking it up and using it makes me happier.

Drawing my thread through the edge of my wax cake to wax it

4. Learn to use a thimble.

If you’ve tried using a thimble once you probably found it horrible and awkward, and left off using one. That’s what I did (despite having worked with a traditionally trained tailor and seeing the amazing things he did with a thimble) until I started hand sewing so much that I was regularly wearing holes in the pads of my fingers – and consequently bleeding on my fabric, or wearing holes through my thumbnail from pushing. So, out of desperation I took up thimbles again, persevered until I had learned how to use one, and let me tell you, they are amazing. They protect my fingers from stabs and wear holes, and cut down on arm strain.

As with needles and thread, having a good quality one, and the right one for how you sew, is the key. I don’t have any quick answers to what is the right one: for me it was a matter of trial and error, feeling which thimble fit, which I could use to push the needle through best, which protected my finger, and which finger to wear it on. I don’t always wear them on the same finger, and sometimes I sew wearing as many as four thimbles at once.

5. Don’t think you need to know a bunch of fancy stitches!

You only need to know 3 stitches (well, 3.5, since there is a forth that is a combination of the first two) to do most historical (pre-sewing machine) hand stitching: the running stitch, the backstitch, and the whipstitch. The most common stitch of all (stitch 3.5) is the running-backstitch – 6 to 10 running stitches, one backstitch, and on you go. It’s stronger than the running stitch, but not as labour intensive as the backstitch. I’m not going to do tutorials because there are dozens on the internet already – you can have fun with google and youtube and find one that makes sense to you.

Running backstitches on the vertical bodice seam of the 1813 Kashmiri dress, backstitches hold the heavy skirt on

Whipstitched rolled hem

Teeny-tiny whipstitches on the lining of Ninon’s bodice, large running stitches (basting) hold the un-bound edges together

Other than practice, those are the things that I find make hand-sewing fast, easy and angst-free. I hope they help your hand-sewing, and if you have any other tips please do share!