Next fortnight’s challenge in the Historical Sew Fortnightly is Peasants and Pioneers. It’s all about making clothes for the lower classes – the most common group, but also the ones whose clothes were the least documented, and the least likely to to have survived.

I’ve got a serious soft spot for the clothing of the lower classes across almost all periods. They may not be as bright or sparkly as the clothing of the upper classes, but they often managed a restraint and elegance that the fancier clothes of the wealthy and fashionable of certain periods (*cough* *cough* *Elizabethan*) were sorely lacking in. Their practical nature quickly weeded out any cumbersome additions which made work difficult.

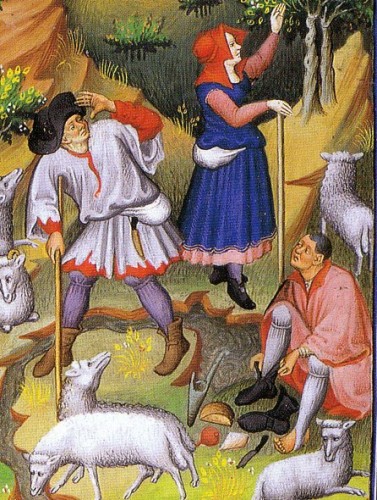

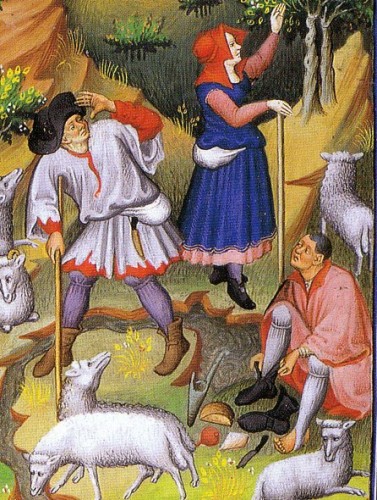

I think my favourite peasant outfits and images are those from medieval manuscripts and Books of Hours from the 15th century. The details are just so clear (look at the beautiful torn and ragged sleeves on the white tunic in the first image below), and the colours so vivid, though the clothes probably weren’t so bright in real life. Still, the bright primaries are so delicious – the pages just look like jewels.

Shepherds, 1430s

Shepherds dancing, 1450s, Belgium

My first attempt at a historical outfit was a Flemish peasant gown, so I’m always going to feel a bit nostalgic about those. There are so many Flemish genre paintings showing peasants (there is a nice selection here), and the area is so well researched that it makes it a very easy entry point for Renaissance costuming.

Pieter Aertsen , c 1508-1575, Market Woman

A century later another Pieter famously portrayed peasants in a much more earthy fashion. I love his ‘Village Holiday’ and the way he has caught the dancers exuberance. One can presume the villages would be wearing their best clothes, but its still a fantastic portrayal of lower class garments of the time.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564—1638) Village Holiday, ca. 1610

Just as good, if not quite as original, is the replica Pieter Bruegel the Elders Peasant Wedding Dance. Just look at the pleats on the back of those skirts! The codpieces though? Not something I ever aim to make!

Pieter Brueghel the Younger or workshop (1564—1638), Peasant Wedding Dance, Replica of a lost work of Pieter Bruegel I, known from an engraving by Pieter van der Heyden, 1610, Louvre

Far less cheery (because really, being a peasant often wasn’t that cheery) is Le Nain’s sombre portrayal of a peasant family. The young woman’s skirt pleats are still fabulous though!

Attributed to Louis Le Nain (1593—1648) or Antoine Le Nain (1588—1648), Family of Peasants, 1642, Louvre

The 18th century saw both the romaticisation of the peasant, and the peasants revolts. Here is a bit of romaticism with just the tiniest nod to reality (Boucher, of course, never painted anything that wasn’t pretty).

Peasant Woman from Around Ferrara Edme Jeaurat (French, Vermenton 1688—1738 Paris) Artist- After François Boucher (French, Paris 1703—1770 Paris), 1734, Metropolitan Museum of Art

If you want more 18th century working-class inspiration, Heileen has an excellent pinterest page.

A very different glimpse of a very different type of peasantry (to use the term in its broadest sense) is given in Agostino Brunias’ depictions of life in the Caribbean in the second half of the 18th century, where he particularly focused on the interactions across the class, and racial, hierarchies. His work is fascinating on every possible level.

Agostino Brunias Italian, ca. 1730-1796 (Italian), Free Women of Color with their Children and Servants in a Landscape, between 1764-1796, Brooklyn Museum

One of my favourite working-class garments ever is the red woollen cloaks worn by country women in England throughout the 18th century, and into the mid-19th century. In the 18th century they were apparently worn by all classes in the country, but by the 19th century the red wool cloak was almost exclusively the domain of the rural working class, and instantly signalled this in contemporary prints. I’d be making one for this challenge if I could only find the perfect red woollen fabric.

Woollen cloak with silk lining worn in Mobberley in Cheshire by a country bride arriving for her wedding, ca 1800, Manchester City Galleries

‘Country Woman’ in Picturesque Representations of the Dress and Manners of the English, Murray, Mr John, W. Bulmer & Co, Manchester City Galleries

Another traditional country garment that I adore is the English farmers smock – worn by farm workers in the south-mid England from the early 18th century into the early 20th century. The smock, and it’s association with rural industry and a perceived ‘wholesome’ lifestyle led to the use of smocking in later 19th century Aesthetic dress. It was the 19th century version of pastoralism and noblewomen playing at being shepherdesses

Detail of Found by Dante Gabriel Rossetti showing a shepherd wearing a smock-frock, 1854

Also, aren’t the gaiters in Found fabulous?

As a contrast to all the farmers gear, Francis (Frank) Meadow Sutcliff’s documentations of the lives of the fisher people of the village of Whitby in England in the 1880s never fail to move me. He captures the same sense of a moment of energy that Brueghel does, and among the static poses of 19th century photography, this is all the more amazing, although his subjects would also have had to pose. What really intrigues me is how much the clothes, at least in their general outline and aesthetic, resemble those of Brueghel’s Renaissance peasants.

Frank Sutcliff, Fisher People, Whitby, 1880s

Another form of the common man are the servants who waited on the fashionable elite. Those who worked in the public view often wore livery based on decorative but outdated fashions, but behind the scenes simpler garments prevailed.

I’ve focused rather heavily on peasants so far: what about some pioneers? Pioneers are both those who went further and endured hardships to explore their own country, and those who risked it all for a new life in a new country. Immigrating to a new country always entailed a balance between the old traditions, and the new culture. I think this dress is a fascinating example of that balance. The fabrics, embroidery, piecing and apron of the outfit are taken directly from Mrs Shimn’s Eastern European roots, but the bodice is cut and styled like a fashionable 1880s blouse.

While I love the dress above for it’s uniqueness, I think it’s time for some pioneers who are a bit closer to home for me.

I wonder what these Portuguese workers setting out for Hawaii in the 19th century though their new life and home would be like? I love all the children’s garments, and how they reflect the newer, more modern, fashions, while the woman is still in the more traditional peasant garb of the Azores. The Portuguese had a major impact on Hawaiian fashions, introducing palaka, a distinctive check pattern, which has become a traditional fabric pattern in the islands.

Portuguese immigrant family in Hawaii during the 19th century

Finishing up my Leimomi-centric look at peasant garb, I return to another traditional workers garment that was romanticised and appropriated by the fashionable elite: the Romanian peasant blouse. Queen Marie of Romania (who almost married her first cousin, George V of England) took to wearing traditional Romanian garb to illustrate her devotion to the country and people she had adopted through marriage. When she wore Romanian peasant blouses in Paris, she became a style icon, and the garment was widely used for inspiration by fashion designers and artists – Matisse sketched and painted a whole series of women in ‘La Blouse Roumaine’ at the end of the 1930s.

Marie and her children Marie (Mignon) and Nicholas in traditional Romanian attire, c. 1908

Marie lived a rather wild and interesting life (rather like her cousin, Princess Alice of Greece), but her devotion to the Romanian people never wavered, and at the end of her life she became a Baha’i.