Cording is evil.

After pintucks, and the Briar Rose Corset, cording makes #3 evilness.

I’m making an 1890s corded corset. It’s based on a pattern in Jill Salen’s Corsets: Historical Patterns and Techniques.

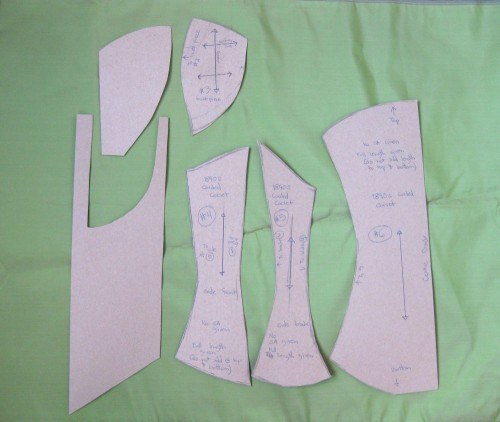

The pattern is kinda weird and insane. Look at my pattern pieces:

Starting from the centre back on the right, it looks totally normal. Basic princess seam, basic side back princess seam, basic side front princess seam, and then you have your….what the heck is that!?!

That, dear readers, is the front piece, with a set in bust.

The problem with the set in bust is that 1) it gets set into a 3.5cm opening in the front piece (and I don’t know if you have ever measured one breast, but mine isn’t 3.5cm across!), 2) the original corset was sized for someone very short, with a very large cup size, so needed a lot of resizing, 3), resizing bust cups is horrible and tricky and 4) once you have figured out all the fitting issues, actually setting in a double bust inset isn’t easy.

But before I get to the setting in the bust bit, I had to sew the aforementioned evil cording.

But first I should tell you about fabric.

I’m using a gorgeous black silk satin recycled from an obi for the outer of my corset, a dark pink vintage cotton for my lining, and obi lining cotton for the interior support.

I sewed my cording between the black silk and the stiff obi cotton.

Basically every single piece of the corset excepting the front piece is fully corded. That’s a LOT of cording. My corset is corrugated.

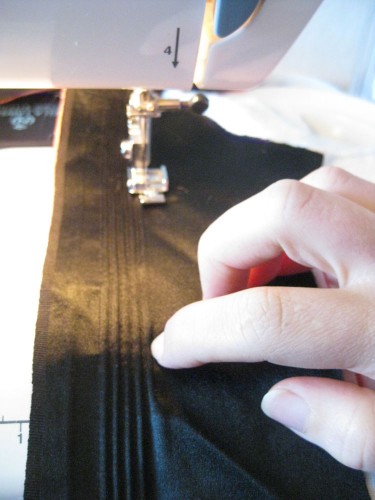

To sew the cording, I marked the centre cording line in each pattern piece with chalk, and then sewed a line of stitching along that line. Then I used the zipper foot to sew a cord snuggly up against the line of stitching to start my cording.

Additional lines of cording get smashed up against the started cording line. I would maneuver the fabric with my left hand, and use my right index fingernail to push the cord up against the stitching and press in a crease to sew along, keeping the cording nice and tight and even.

And every three cording lines or so I would sigh and come up with a new creative not-actually-a-swear word and wonder why I did this to myself.

But for all that evilness, the corset is almost done, so I’ll show you more progress pictures in just a day or two!