For my first guest writer for the terminology series, I’m very excited to introduce Cathy Raymond, of Loose Threads: Yet Another Costuming Blog.

Cathy’s Medieval and earlier focused blog is one of my favourite textile reads because her area of research is well outside my usual scope, meaning that I learn something new with every post. At the same time, her writing is so thoughtful and considered that it makes me continually realise how timeless and universal textiles are, and how relevant the way we think about the scraps of fabric found in Viking burials (for example) is to the way we think about fashion and textile design today. So without further ado, Cathy:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hello! I’m Cathy Raymond. The Dreamstress has asked me to contribute a guest post about an item of costume terminology characteristic of my preferred area of costume research, namely, the Migration Period and that part of the early Middle Ages often called the “Viking Age”. Unfortunately, as one delves back into what is known about costume in these periods, it quickly becomes clear that we seldom know what the original garments looked like, let alone what the people who wore them called them. A good way to illustrate the types of problems that arise is to discuss a favorite subject of mine: the so-called “Viking” apron dress.

Most members of the SCA (“Society for Creative Anachronism”), and most fanciers of historic costume who surf the Internet have heard the term “apron dress” and have a vague notion that “Viking” women wore them. Leaving aside issues about the correctness of referring to the inhabitants of what is now Sweden, Denmark, and Norway during the ninth and tenth centuries C.E. collectively as “Vikings”, there are two big problems with the idea of the Viking apron dress: 1) We don’t know what the garment looked like, and 2) we don’t know what the women who wore it called it.

To explain how we even know there is such a thing as an “apron dress” at all, let alone how we ended up with this term and the other terms used for it by modern historians, researchers, and reenactors, it’s necessary to describe a little bit about our sources of information about the garments themselves.

Virtually all of the surviving textile remains from the Viking period in Scandinavia come from the ground, particularly from graves. Because burial is tough on cloth under most soil conditions, most surviving textiles are very small, from the size of a fingernail to the size of a postage stamp, and many of the larger surviving pieces are ambiguous in shape and as to their original purpose.

One feature of Viking women’s graves that has helped greatly with the reconstruction of their costume is the fact that they were typically buried with lots of metal jewelry, most of which was made of bronze. Metal salts from bronze objects, given the right soil conditions, may replace the actual fibers of a textile, creating an object called a pseudomorph that preserves the form of the original textile so completely that the attributes of the individual fibers can be measured.

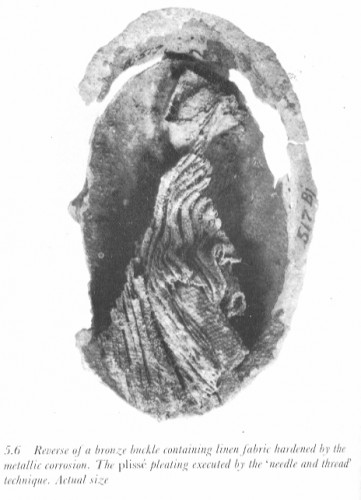

The underside of a bronze brooch with strap remnants and pleated shift remnants from one of the Birka graves; from Geijer in Cloth & Clothing...

As a result, many of the textiles found in Scandinavia were preserved on and about the bronze jewelry and tools with which women of the Viking period are buried. A common feature of Scandinavian women’s graves of the period are large, bronze brooches often referred to in English as “tortoise brooches”. Those brooches often contain remains of narrow fabric strips or loops, each of which was made by folding a narrow piece of cloth in three places and sewing the outside two folds together, creating a strap about 1 cm wide. Sometimes, other types of fabric scraps survive near tortoise brooches and their loops, and it is entirely from these finds that the existence of the Viking era overdress has been deduced, as well as from the fact that fabrics other than the loops themselves are found, both clinging to the brooches and in other sections of the graves. The accompanying photographs are reconstructions I have made based on different theories of the overdress construction and different archaeological textile finds, the details of which are beyond the scope of today’s post.

Finnish president Tarja Halonen in a reproduction based on textile and jewelry finds in a grave at Eura, Finland, dated to approximately 1000 C.E

So where did this overgarment with loops come from? The best guess we have, right now, is that it is the descendant of an earlier garment, called a peplos, that was worn by the ancient Greeks and Romans. Peploses were worn later in time in many northern European areas, such as in Anglo-Saxon England, and evidence that a similar garment was still being worn around the year 1,000 C.E. was found in a grave in Eura, Finland. The earliest peploses appear to have simply been a large sheet of fabric folded around the body and pinned at the top edge with a pair of a type of long brooch called a fibula. The top edge could be folded down before the pins went in, or not. By the time of the Romans, these dresses had become voluminous and had straps at the top, though they do not seem to have been worn with brooches. These voluminous drapey overdresses were worn by married women as a sign of their marital status and called (confusingly, for English speakers) stola.

That gets us back to terminology.

The archaeologists who have analyzed the grave finds and told the world about the loops inside the brooches also used descriptive terms for the garment they believed it denoted. They wrote in German, or Swedish, or Norwegian, or Danish, and invented terms languages to try to capture their image of what the actual dress must have looked like. Agnes Geijer, who was Swedish but wrote about the Birka finds in German, called the garment a hängerock, a German word which has been translated into English as “hanging skirt”. More recently, Swedish researchers have used the Swedish word hängselkjol for the garment. The word träggerock, which I’m told is German for “strap skirt,” has also been used. British reenactors have called it a pinafore, a term for a modern overdress of similar shape. Russian researchers refer to it as a sarafan, even though the Russian sarafan is a much later period garment, and Russian women (other, perhaps, than those influenced by Scandinavian culture) did not wear an overdress that was even remotely like the “apron dress” during the Viking Age.

So far as I know, the American term for the garment, “apron dress”, was devised by Carolyn Priest-Dorman in the early 1990s, and because it was featured in an SCA publication (Compleat Anachronist # 59, which is still worthwhile reading for a novice to the issues relating to Viking era costume, though it needs an update in light of more recent research), and it is in common use among Viking enthusiasts in the SCA. But “apron dress”, like all the other terms for the Viking era overdress worn by women in Scandinavia, is a modern invention, functioning to allow modern scholars and reenactors to discuss that overdress (including theories of its form and construction) with a minimum of circumlocution.

Finally, British researcher Thor Ewing thinks he has ascertained what the Viking women actually called the “apron dress”. He believes it was called smokkr, based on his reading of the Viking poem RÃgsþula. The relevant passage reads, in the original Old Norse:

Sat þar kona/sveigði rokk,

breiddi faðm/bio til vaðar;

sveigr var a hofði/smokkr var a bringu,

dúkr var a halsi/dvergar a oxlum.

This passage is usually translated along these general lines:

The woman sat/and the distaff wielded;

At the weaving with arms/outstretched she worked;

On her head was a band/on her breast a smock;

On her shoulders a kerchief/with clasps there was.

Ewing believes that “smokkr” does not mean “smock”, as the word has usually been translated into English, but refers to the item that has been called “hängerock”, “pinafore” or “apron dress” because of the reference to clasps or “dvergar” (literally “dwarves”) on the woman’s shoulders. Ewing believes that the term “dwarves” refers to the big tortoise brooches worn to hold the overdress in place on the body. He believes that the proximity of the term “smokkr” to the term “dvergar” means that the “smokkr” was associated with the brooches, which would mean that the “smokkr” could only be the garment held up by those brooches–i.e., the apron dress. Moreover, Ewing believes that the term “smokkr”, which derives from an old Norse word meaning “to creep through” indicates that the apron dress could not be a wraparound garment:

The word smokkr could not be easily applied to an open garment which is wrapped around the body, as in the reconstructions envisaged by Geijer and Bau. It is worth noting that the English word ‘smock’ typically describes a longish garment of cotton or linen, which is put on over the head and often includes a pleated section on the breast. (Viking Clothing, p. 39).

I’d like to believe that Ewing is right and the Viking women did call the garment smokkr, because the idea that the RÃgsþula contains evidence for how the apron dress was constructed is attractive to me. There is evidence that at least some apron dresses had a pleated section in the front. But although Ewing’s reading of RÃgsþula is persuasive, it’s not conclusive; for a start, we do not know that the word “smokkr” was only applied to the apron dress. It’s also possible that the “open garment envisaged by Geijer and Bau” is a more recent version of the garment that nonetheless kept an old name that no longer correctly described it. In the meantime, it seems likely that the use of a variety of non-period, vaguely descriptive terms for the Viking era overdress will continue into the indefinite future.

Sources:

Ewing, Thor. Viking Clothing. Tempus Publishing Ltd. (2006).

Geijer, Agnes. “The Textile Finds From Birka,” in Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe, pp. 80-99. Heinemann Educational Books Ltd. (1983).

Good, Irene. Archaeological Textiles: A Review of Current Research, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 30, pp. 209-226 (2001).

Kies, Lisa. “Fabric Treasure.” Lisa Kies’s English translation of a short writeup of a fabric find in Pskov, Russia, with tortoise brooches and photographs.

Kies, Lisa. “Women’s Clothing in Kievan Rus”

Krupp, Christina & Priest-Dorman, Carolyn.Women’s Garb in Northern Europe, 450-1000 C.E.: Frisians, Angles, Franks, Balts, Vikings and Finns(Compleat Anachronist #59). Society for Creative Anachronism (1992).

Lewins, Shelagh. “A Viking Pinafore”

McManus, Barbara. “Roman Clothing: Women”

Owen-Crocker, Gale R. Dress in Anglo-Saxon England. Boydell & Brewer, Ltd. (rev. ed. 2004).

The text of “RÃgsþula” can be found in many places on the Internet, but this site includes the original text with a modern English translation, side by side (the portion in which the “smokkr” text appears is cited).

Wow! This is a really interesting piece 😀

Much to ponder on now!

Most enjoyable! Thank you for sharing.

Fascinating. Thanks so much Cathy for contributing this post and Dreamstress for organising the guest post series.

The last picture looks like it’d make an ideal maternity dress. I wonder if “Viking” women constructed these dresses in a variety of ways according to what they liked the look of or what functionality they wanted. There seems to have been a lot of variation insofar as we can determine, so perhaps there was no hard and fast rule for making apron dresses. It looks to me like the overdress was there for warmth (those layers would trap heat well) and for wealthy women to display bling and expensive fabrics, so perhaps conforming to a specific style of construction wasn’t the point.

I don’t know much about Viking clothes (hence I asked Cathy to guest post!) but, based on basic styles in cultures all around the world, I suspect that there would be a basic style, and people would tweak it according to needs and means.

It really amazes me (even though I know exactly why) that we know so little about Viking dress, but there is so much record of earlier Roman dress.

I don’t really know anything about Viking clothes either, though I studied the “Viking” societies when I did history at uni. There was a fair bit of stuff about women and division of domestic labour and the socio-cultural importance of the textile industry as well as the politics, economics and looting, but clothing seems to be something a lot of Viking historians bypass. Lack of evidence, I guess.

An interesting thing I do know is that textiles were often associated with magic in these cultures. Women wove spells into their textiles. So based on that I like to speculate that the overdress sometimes had a talismanic function.

interesting, though in one of my costuming books it shows very well preserved pieces of clothing found in grave sites in peat bogs in denmark. although the examples are significantly older (it says 3rd to 5th century).

There are certainly older textile finds than the Viking age ones I talked about in the above post. I’ve been reading a book by Margareta Gleba called Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy that discusses some of the very early Italian finds, including a few nearly complete semicircular cloaks that have been dated to the 8th century BCE! But survivals like that are pretty rare anywhere.

Ah, you are talking about the bog mummy clothing, like Huldremose woman.

Those are fascinating – I lecture about them. The really interesting thing about them to me is that even though they tell us all about the weaving and sewing technology that was available, we still have no idea if their clothes remotely resemble what ordinary people wore in everyday life, as the bog mummies were clearly part of some ritual. They have done tests on the bog mummies hair and teeth, and it shows that they ate very poor diets up until a few weeks before they were slaughtered/sacrifised, and then suddenly their diets improved drastically, and their hair and nails were groomed. So they were lower members of society who, for whatever reason, were treated incredibly well for a few weeks, and then brutally murdered and tossed into the bogs, often with clothes and other artifacts.

in response to both of the replies:

wow that’s amazing! yeah I was just really surprised by the above post. I thought that a lot of the clothing in that region were pretty well preserved (my book has very broad ranging chapters) i really don’t know a lot about, well, early or late middle age clothing in general. just thought it was interesting that there are some really well preserved clothing from 500 or so years earlier but very few examples from later on

And just in response to the latter response:

the bog lectures sounds really interesting, all your lectures do. wish I could attend one!

It’s pretty amazing how chance or a little cultural or climatic quirk can preserve one group of textiles, and leave us so little from another, isn’t it? It never fails to intrigue me.

The lecture on bog mummies is something I do as part of a textile history course.

It’s worth noting that the Huldremose find (the one with the tube-shaped garment that was probably a peplos) is much earlier than the Viking era–probably Roman times:

See this excerpt from Dress in Anglo-Saxon England by Gale Owen-Crocker:

http://books.google.com/books?id=sQFllXEXQ-QC&pg=PA43&lpg=PA43&dq=huldremose+peplos&source=bl&ots=2tB__V3bS-&sig=TW4ZnA3lPkFtFmqUABzGVaUhe1o&hl=en&sa=X&ei=3qYXT5_JAcn10gH9jtXgAg&sqi=2&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=huldremose%20peplos&f=false

Ah! Thank you for clarifying. I have a series of images of it recreated along with all the other bog clothes (I think the recreations were done by the national museum in Denmark? would have to dig up my notes), and my mind has just lumped them together date/wise. It did seem very odd that one was so peplos-y, and the others quite a bit more structured.

Sometimes enough of a textile from a burial survives that you can tell that it had wear on it when it went into the grave. That’s pretty good evidence that it was a previously used item of clothing, and likely one that was used in everyday life. Conversely, sometimes you can tell that a burial textile could NOT have been worn in real life, that it must have been made specially for the grave. You see this in some high-status burials of the 17th and 18th centuries CE, for example. But the usual circumstance is that only fragments remain, and it can be hard to tell what was going on with the costume in that case.

Wow! Interesting. There is a little city near me that was settled by Icelantic People (Gimli). Every summer they hold a festival and one feature is a Viking Village. Some folks dress as Vikings, live in tents and share with visitors displays and demonstrations. They held a mock battle once that totally caught my youngest boy’s imagination. I almost had him convinced to join the group. (They don’t really care if you are Icelantic but with my boy’s German background and English background he likely has some of that blood in him!) There is something very romantic about the idea of Vikings!

It is incredibly interesting how the bronze objects often make a pseudo cloth from the metal salts. You can almost see the weave and weft of the cloth.

Loved the terminology post and I look forward to seeing what the other guest posters come up with!

Em

You are correct that I coined the term. I called it “apron-dress” to emphasize the fact that the garment was not the two-panel apron type thing that so many SCA and reenactor Vikings believed it was. That is, I was trying to change the concept from “apron” to “dress that has straps like an apron.”

Very interesting! I used to have a copy of the book in Finnish with then-president Halonen in the reconstructed national dress… don’t recall the name of the book now. Do you happen to have it listed in your resources?

As I have been looking at re-enactment costumes for the Viking era, I wondered how the woman would nurse her infants in the enclosed “Apron” dress over a tunic. It seems to me that this would be the primary function of the overdress so an open sided apron would allow a woman to nurse her infant while maintaining a blanketed warmth for them both. The under tunic would then have to be designed in such a way as to enable easy access for the infant, but I have only so far seen under tunics that are slotted across the neckline, rather than slit down the middle. I would venture to speculate that the style of the over dress would become an indicator of a married woman simply due to the function of allowing that woman to effortlessly nurse her infant, whereas a girl or woman who was not married might wear a closed over dress.

With the dress in the last picture, it wouldn’t be difficult to hide nursing access in the pleats. Folkwear patterns sells a pattern for a Russian folk costume that isn’t too dissimilar, and I have made it with breastfeeding access. It makes a cute sundress/jumper for everyday wear.

I’m intrigued by the last line of the poem:

“On her shoulders a kerchief/with clasps there was.”

I’ve never seen any reenactors or SCA folk wear such a thing. Any idea what that would have looked like?