Spending the night at Kalaupapa is amazing. I grew up in a very rural location, and our house now is set well off the road, and is very quiet, but neither of these begins to compare to the tranquility of Kalaupapa. Unless there is an activity which everyone is attending the entire town goes to bed early. There is no distant traffic, no early flights at the airport, no murmur of late night businesses and parties: just the wind and the waves.

You sleep deep, and wake early, to the sunshine spilling across the pali, highlighting each ravine in the cliff-face, and bathing the whole peninsula in a reflected glow.

After breakfast and devotions (we were doubly lucky to be there on the Baha’i feast of Might – like Sabbath), we headed out into the sunshine, walking through the tiny township, past the gravesite of Mother Marianne Cope, who came with her nuns to Moloka’i from upstate New York in the 1880s to help Father Damien.

Fifty other religious orders had turned down Hawai’i’s plea for help from a group of nuns, for fear of catching the disease. Marianne promised her nuns that none of her order who served in Hawai’i would contract leprosy: a reasonable promise to make in the light of modern medical knowledge, but a giant leap of faith in the face of 19th century attitudes towards leprosy, especially as Father Damien was dying of the disease. Her promise held true, the faith and assistance of her and her comrades was unflinching and invaluable, and in October Mother Marianne will be made Saint Marianne of Moloka’i: the second Catholic saint to come from the tiny corner of our tiny island.

Beyond her grave are more lighthearted reminders of Kalaupapa’s legacy. First, a garage adorned with license plates from all over the US, the legacy of all the people that have come to work there, and all the cars that have ended their life in Kalaupapa. The barge only comes to Kalaupapa once a year (its annual visit is a memorable event), so that is your only chance to get a car in, and no car ever goes out. Because the county is so small and sparsely populated, and has such a unique set of laws, the driving and licensing rules in Kalaupapa are quite loose compared to the rest of to the state of Hawaii. Legally blind patients have been allowed to drive, and for a while there was a car on the peninsula that only drove in reverse.

Regular cars aren’t the only thing that end their life in Kalaupapa. Old schoolbuses have been brought to the peninsula to serve as tour buses, and as we hiked down the pali we could see the big yellow bus whizzing around the roads, carrying the tour group on seats that I probably sat on as a schoolkid.

For all the fun stories, reminders of Kalaupapa’s past are never far away. Every turn of the road brings a new graveyard, snuggled against the pali or spread out by the sea.

In the newer graveyards the Hawaiian on the old gravestones has given way to English, and the last names show how ruthlessly democratic the disease was, striking all races and walks of life. The gravestones are much fancier than in cemeteries in other parts of Hawai’i, lending an odd grandeur to the regularity of death on the peninsula (one former patient talked of the constant ringing of churchbells, day after day).

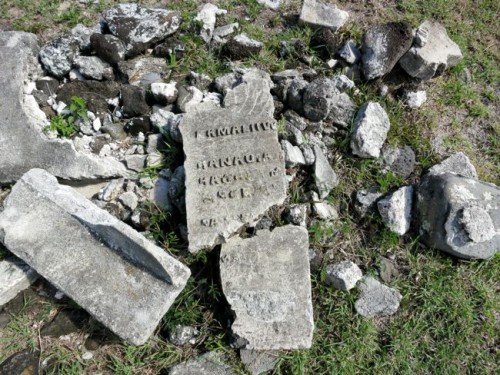

For all the grandness of the memorials, nature is fighting back, breaking down the stones and re-claiming the edges of the cemetaries.

For the historians and archeologists at Kalaupapa, and for those who have family buried there, honouring the history is a delicate balance between conservation, nature, and restoration. A gravestone lying broken on the ground will continue to disintegrate, a stone wall fallen into disrepair will turn into a jumble of stones, no matter how carefully you monitor the placement of the stones. Is it better to rebuild the wall, to re-erect the gravestone, and fill in the missing pieces, in order to preserve the bits that are left?

These questions plague those in the history and museum fields everywhere, but in few places is the question more poignant than at Kalaupapa. What is the best way to honour the history, and to memorialise the people who lived there?

The same questions of history and memory have had to be tackled by the National Park Service and the Board of Health in administering and making laws for what must be the most unique national park in the US. How do they make the park accessible to visitors, while respecting the former patients who still make the park their home? It’s a question that affects every aspect of life. At the moment, 100 visitors a day are allowed on the peninsula, but only as an invited guest of a resident or as part of an official tour. Only former patients are allowed to own businesses on the peninsula, so the tours are run by former patients. There are only 13 former patients left, 7 of whom live on the peninsula full-time. What will happen when they are all gone? That’s still to be decided.

Other discussions and rules are less obvious. Because there are so many archeological sites and gravesites on the peninsula, no digging is allowed, so anyone who wants to have a garden has to create a raised bed with fresh dirt. There is also an ongoing discussion about what to do about housing. In past decades, when a patient passed away and their house would no longer be used the houses were burnt down, as caring for them took too much in the way of resources. Now the remaining houses that don’t belong to patients are used by the NPS and the State to house employees, leading to another discussion about the houses. Should they be kept as they are, with 1950s kitchens and simple rooms, as living pieces of history, or updated to make them more modern and comfortable for the people who live there? (having been in them, seen ’50s plantation style houses in Hawaii vs. very un-tropical modern remakes, I am a massive supporter of the ‘leave them as they are’ camp).

There are also discussions about how the visitors who come to Kalaupapa get to use the peninsula. One rule that surprised me (until I thought about it) prohibits surfing. Why? Kalaupapa is said to have the best surf on Moloka’i: so coveted were the waves that in ancient times only the chiefs were allowed to surf on them. Residents were afraid that Kalaupapa would become a surf destination, and the history would be lost beneath the commerce, so surfing is not allowed. Hunting, on the other hand, is not just allowed but encouraged, because the peninsula is over-run by introduced axis deer, goats and pigs, all of which cause havoc to the natural environment. Kalaupapa has become a little bit of a hunting destination (though you still have to be an invited guest), but without it their would be a major environmental disaster.

Finally, there is the rule that kept me from visiting Kalaupapa as a child: no visitors under 16. I had thought this was simply to prevent children from gawking and unthinkingly saying hurtful things, but the real reason is far, far more tragic. Throughout most of the 20th century patients at Kalaupapa who had children had their infants taken away from them at birth (patients were not even allowed to hold their child once, so some hid their pregnancy and the birth to get a little time with their child), and adopted away. In an attempt to prevent the stigma of the disease from following the child, their birth certificate would be altered to give a different place of birth, and they would be adopted to families on the US Mainland, to further separate them from their history. The authorities had the best intentions with this practice; they wanted to protect the child from contracting leprosy, and from the stigma associated with it, but the reality of what happened is heartbreaking. For patients who had their children taken away, seeing other family’s children was just too hard a reminder, so no children are allowed on the peninsula.

I’m sorry. I’ve made you cry. I’ve made me cry too. Let’s look at some beautiful images of the coast, take a deep breath, and move on to something happier.

How about the other things that Kalaupapa is protecting, in addition to it’s history? The deserted beaches provide the perfect place for the endangered Hawaiian Monk Seal to rest and breed, and so, for the first time in my life, I was lucky enough to see them.

Sitting on the rocks along the coast, watching the mother and her almost grown pup (the darker one) as they sunned themselves and occasionally turned their heads to check up out, in the absolute peace of Kalaupapa, was amazing. Only the tragedy of the past has made this place safe enough for these rare animals, so another piece of good has come out of what happened.

After a morning by the coast, contemplating the memorials, chatting with our hosts, watching the monk seals and the waves, it was time to head back up the pali, to home. We took one last look at the beach, the township, and the view of the trail heading up the cliff, gave our hosts a hug, and we were on our way, with lots and lots of water.

We were silent starting the hike, each thinking of all the things we had seen, and heard, and experienced. Then Mum said that she felt so moved she needed to sing, and so we started the hike on a melody, singing “There is an ocean, an ocean, an ocean of light, where the rays of the sun and the raindrops unite…”

After a while we fell silent again, and began the hike to nothing but the sound of the wind sighing across the peninsula, and the endless woosh of un-surfed waves.

an emotional journey for us as we read your words. a very sad but beautiful place.

What a series of beautiful and emotional posts. Thank you for sharing your journey & your photos and for reminding us of a piece of history that should never be forgotten.

Bitter sweet history. Thanks for sharing.

Dear Leimomi,

I’ve followed your blog happily for several years now. These three posts have been the most moving among all of them, and have introduced your readers to a place and a history that must be remembered.

Am wondering if there is a chance that the posts might be published formally somewhere, say in a Hawaiian newspaper, or in a New Zealand one, or in an historical society journal? The story is so beautifully told that it deserves a very wide readership.

Very best,

Natalie

I agree. You’re a good writer in general, and this stuff is subliminal. And the subject…

Hear hear! I absolutely agree that this should at least be linked to by the Hawai’ian Historical Society or the Kalaupapa History site or whatever else it out that. Getting it published in a historical magazine would be perfect.

Three fascinating and moving posts which will stay with me for a long, long time. I can see why you found it hard to write about, thank you so much for sharing.

wow, incredibly sad, but so very beautiful and peaceful looking. Thank you for sharing this very well written journey and lovely photos.

I have read your blog for ages and have yet to be so moved by such a beautiful and comprehensive post about a difficult and personal issue. I read all three posts at once while at work and had a hard time explaining the tears. Thank you for sharing this piece of yourself and your home with your readers.

The way you talk about Hawai’i makes it clear how much you love it. Your photos are gorgeous and I like the way you presented the history as tragic and tangible but also distant, much the way I imagine Kalaupapa must have seemed to you, growing up. This 1897 map of the island of Moloka’i is making the rounds on a cartography Tumblr and thought you’d like a look: http://96.125.172.23/~tumblr2/molokai_1906.jpg

Thank you for sharing that map! I’ve not seen it, and it’s amazing – or at least the bits I can see are. I can’t get it to load fully. 🙁 It’s actually from 1906 btw.

These posts were incredibly touching and I cannot thank you enough for sharing this with us – your photos, your history and the story of your home.

Oh, thank you! I’m so privileged to have had this experience, and to have been able to convey even a little of what it meant to me.