I love paisley (the design) and the history of Kashmir shawls. The interaction between the paisley design and Western fashion is fascinating, with both elements impacting the other in equal fashion.

Kashmiri shawls were first introduced to Europe in the late 18th century by English traders who had encountered them in India. In India the shawls were worn by men, but in Europe they were taken up by women as the perfect warm wrap to accompany to new light muslin dresses. The cashmere wool was lighter, softer and warmer than anything available in Europe at the time, and the paisley patterns were deliciously exotic to Western eyes. Kashmiri shawls were also the perfect status symbol – they were extraordinarily rare, and prohibitively expensive.

As with anything rare, expensive and incredibly desirable, those who could afford it flaunted it, and those who couldn’t scrambled to find a cheaper alternative. Manufacturers in Europe almost immediately began to replicate paisley designs (the name paisley comes from Paisley in Scotland where many imitation Kashmiri shawls were made) on wool-silk blends and on cotton, and even in India fakes were made.

As the fashion for Kashmiri shawls spread and the importation of real Kashmiri shawls and manufacture of replicas made them more common the design moved beyond shawls, and paisley motifs were seen on dresses and cloaks. Sometimes these items were made from actual shawls (Kashmiri or European), and sometimes they were made from fabric specifically woven with paisley designs.

The ever fashionable Josephine de Beaunharnais, then Empress of the French, was certainly the most famous person to wear a paisley shawl. Gros painted her wearing a very simple tunic dress made from a Kashmiri shawl (this being Josephine, we can be sure it is real) over another dress, and a shawl as a shawl.

Empress Josephine by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, ca. 1808, Musee d’Art et d’Histoire at Palais Massena, Nice France

The artist Robert Lefèvre loved the look and painted two different noblewomen in dresses made from Kashmiri shawls, though as the poses and dresses are identical down to the last fold we can assume that Salome’s frock probably owes more to the artists imagination than anything the Comtesse actually had in her wardrobe.

Élisabeth Alexandrovna Stroganoff, Countess Demidoff (1779-1818) by Robert Lefèvre, ca. 1805 Hermitage Museum St Petersburg

Fashion plates noticed the trend and disseminated it further.

Dress with paisley design, 1810

Not all frocks were made from real shawls. This frock is of red net over a white undergown with a paisley border, creating the effect of a Kashmiri shawl gown without the weight and warmth.

This gown also uses an fabric which gives the effect of a paisley shawl, and echoes the daring neckline of the Lefevre portraits on a more modest scale.

Evening dress, 1815, cotton & silk, Snowshill Wade Costume Collection, Gloucestershire

The next one is much less sophisticated in its silhouette and construction. The narrower, stiffer paisley design at the hem of this frock is purely European in creation, demonstrating how quickly the design was picked up and adapted in the West.

And not all paisley garments were dresses, as evinced by this charming cloak made from a paisley shawl.

The height of the Kashmiri-shawl-as-a-dress fad was from 1805-1815, but examples were seen into the 1820s, as evinced by the famous Amelie Augustes (her frock was the only 10 out of 10 Rate the Dress ever).

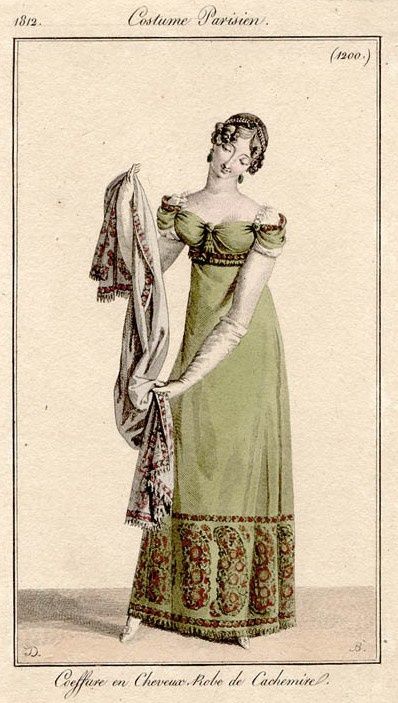

So what does this have to do with me? Well, my project for the Historical Sew Fortnightly Bi/Tri/Quadri/Quin/Sex/Septi/Octo/Nona/Centennial Challenge will be an 1813 Kashmiri shawl gown inspired by this fashion plate from 1812:

I figure that a wool or cashmere dress would be worn in winter, so if this was made in winter 1812, it would certainly have been worn in Jan 1813 – if not for years later. And, of course, women further from Paris and London could wait for months to get the latest fashion plates. I’m having to tweak a few things to fit my fabric, but based on the extend dresses compared to plates, that’s perfectly historical!

I’ve been making very good progress on it, and am so excited about the project! I’ll be showing you my work-to-date shortly.

Oh, my!! I am overcome with envy, desire, excitement, delight – all that stuff. I have long yearned for a Cashmere shawl, a good one, but have never (a) found one available, or (b) had the money to do serious looking. The wonderful delicacy of the design, and the richness of the colours! I really didn’t know that they had made dresses from them – saris, yes, but not these. Goodness, they are almost practical! Where did you get a shawl (or the fabric) to make a dress from? This is going to be a delight to watch.

And I am not surprised Amelie Augustes’ dress got a solid 10 out of 10 – if I had been watching then, I would have joined in.

Happy sewing!

Yay! Glad you are excited! I won’t be using a proper cashmere shawl myself (modern ones are so much yuckier than historical, and less than half the size or Regency originals, so you couldn’t get a full dress out of them), but I did manage to find a lovely twill-weave wool with a border print taken from early 19th century Kashmiri shawls in Global Fabrics a year ago. I’m torn between being thrilled that it’s so close, and bummed that it isn’t perfect – the colours aren’t quite right and there are other tiny details that will be off).

I don’t think making dresses from sari is actually a period practice. I suspect costumers started doing it because they mis-interpreted these fashion prints as saris rather than shawls, and because saris already have the lovely built-in border, and you see a lot of borders on Regency dresses.

Blame Georgette Heyer. I have a strong feeling she mentions someone bringing back Indian saris for ladies to make dresses from. But then she, of course, was only guessing, the dear woman.

Actually, I don’t think “the dear woman” was guessing – she was an incredibly accurate, obsessive-compulsive researcher who went out of her way to make sure that every single detail in her books corresponded to something that was correct to the year it was set in – so she probably found a reference to it somewhere, perhaps an isolated/unique incident, but was notoriously close about her sources (although apparently the family have her pretty extensive collection of scrapbooks/reference books/notes on every aspect of the Regency)

I agree that Heyer was a ridiculously obsessive researcher – unfortunately for me the emphasis on the ridiculously.

Far too many bits of Regency lore are now canon because she found one isolated reference in a diary and stuck it her books. Some of her references were so isolated and obscure that she considered suing other writers for using the phrase/incident (most notoriously ‘make a cake of oneself’) because she was so certain that she had the only reference to it in existence – and just because one diarist uses a phrase or mentions something does not make it common. She tended to ignore the overall context of all her details and research – missing the bits that would have lent them significance and accuracy (like a writer 200 years in the future mentioning the popular dance Gangnam Style without knowing about YouTube, or that it was in Korean). Worst of all, she did not keep notes as to where she sourced her references – making it very difficult for the later researcher to verify or explore the context.

This isn’t to say that I don’t admire Heyer. For a historical novelist, and especially in the time she wrote, her research is phenomenal, and has contributed hugely to our understanding of Regency England. However, as a researcher, I’d never use her books as a source or consider a costuming mention in a Heyer novel as more likely than not accurate.

This is very true. Although the plagiarist – it was Barbara Cartland by the way – did a whole lot more than lift certain phrases – she copied whole plot elements, used suspiciously similar character names, and generally produced books that were so similar to her work (the one I came across was a brazen rip-off of Convenient Marriage with additional lashings (ahem) of the Burbling Bab’s asthmatic virgin beating…)

It would be great if the family could be persuaded to publish the Heyer scrapbooks – from the few glimpses that are out there, they look like quite a resource. I did meet her son once, he was a very nice chap indeed.

Love Paisley! I wore a shirt with a paisley pattern to work and a Persian colleague noted a similarity to patterns in his culture. I notice it is sometimes called Persian Pickle. Persian culture is so rich and fascinating.

I loved living in Spain to where it was spread and evolved into Mozarabe. So neat, so cool.

I bet someone some where made a dress from a sari in period. they are just tooperfect a fabric source for regency gowns 🙂

I have my great-great-grandmother’s paisley shawl. Her name was Sarah Helen Smart (she married a McKee). She wasn’t born until 1848 so hers is later than these dresses. I found it in a box under some leather photo albums, wrapped up in newspaper from 1944. Someone wrote on the paper: “Grandmother Smart’s Paisley Shawl – Very Old.” No kidding!

It’s in really good shape aside from some age stains. The design was woven into a cream-colored fabric (now yellowing) with blue and red fiber – I want to call it thread but it’s more of a yarn. The design goes all around the edges and has bigger paisley swirls in each corner. Two edges have fringe. I think it’s made of wool but I really don’t know. I actually thought it was a tablecloth until I saw the note – it’s big!

I also found a beaded purse, a (long since broken) tortoiseshell hair comb, a handmade lace collar, and a pair of handmade sleeves with eyelets. Back in 2011 when I found all this, Lauren over at American Duchess helped me identify another heirloom as a shuttle – it’s made of metal and has “S H Smart” engraved on it.

The only problematic thing is that although I always say these things belonged to my great-great-grandmother, I can’t be sure they didn’t belong to HER mother, who was born Sarah H. Pearson and married into the Smart name. She lived from 1807 to 1875. If that’s true, then I guess the shawl I have could be a contemporary of those used to make the dresses in the paintings. I’m going to have to look into this!

flickr.comI went ahead and posted the photos I have on Flickr so I can stop trying to describe things I am ill-equipped to put into words.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/60027918@N02/sets/72157632435921791/

Oh lovely! What a wonderful thing to own.

I’ve had a look at the images, and I am sure that the shawl would have belonged to Sarah Helen Smart. It dates to the 1870s or 80s – the colours are absolutely typical of that period, and you wouldn’t see the wider paisley borders until at least the 1870s. It’s almost certainly of Western manufacture, and probably is wool or wool and silk rather than cashmir. Kashmiri shawls were noted for the number of colours used in the weave – Western weavers tried desperately to come up with a technology that would let them weave as many different colours into the shawls as their Eastern counterparts, without success. Unfortunately the Kashmiri weaving secret was lost in a drought/famine/epidemic in the early 1880s (the three so often go together).

Whether Kashmiri or Western, shawl quality depended on the materials used and the number of colours in the design, so a three-colour shawl (like Sarah’s), would have been quite reasonably priced, and of a cheaper material like wool. In a way that makes it more special – the more expensive shawls were more likely to be preserved and end up in museums and collections.

I’d love to know what the dimensions of your shawl are – that could help to date it more precisely.

I hope that is of interest to you!

Thank you so much for the info! Honestly I would have been shocked if you told me you thought it was a genuine Kashmiri. Sarah Helen Smart wasn’t from a very wealthy family – they did quite well for themselves but not that well! She was born in New Hampshire but moved to Michigan as a child and, once married, moved to Illinois and then to California. So it makes perfect sense that her shawl would be later, and Western in origin. The colored threads seem more wooly to me, but the cream-colored ground is smoother and possibly a silk/wool blend as you suggested. I don’t know the dimensions as I’ve never fully unfolded it but I will have to get them the next time I’m at my parents’ house. Thanks again!

flickr.comflickr.comIt turned out smaller than I remember, at 4′ by 3′ 11″. The pattern is the same all around the edges. I put up more photos: http://www.flickr.com/photos/60027918@N02/sets/72157632435921791/with/8422337377/

I even took a close-up of the edges, and one of the fabric weave – it’s what I would consider a twill but I have only the vaguest understanding of fabric weaves. I suggest looking at that photo in its original size for the most detail: http://www.flickr.com/photos/60027918@N02/8422337377/sizes/o/in/photostream/

Oooh, thank you! Will have a good look at them tomorrow. I can tell you it’s definitely a twill weave (the diagonals are what to look for), looks like a 2/1 to me (over 2, under 1).

Fascinating! What a wonderful set of things to have inherited. I think the shuttle is a tatting shuttle – ladies used to do all that lovely edging for undies and handkerchiefs.

How super cool to have inherited all that! Thanks for sharing!

Wow that is such a wonderful inheritance.

Lovely! I love all the wonderful paintings and period garments. I look forward to seeing your project.

OOH! I’ve been ogling the regency sections of my costume books this week and my head is full of this stuff. The mustard LeFevre is by far my favorite.

That was a fascinating read, those shawls must have been really huge if they were big enough to make dresses out of. Regency is not my favorite era, but I actually like these dresses. The borders make them a lot less boring than most regency dresses.

Then again, it’s -15 and snowing out right now, so anything made of wool sounds good to me.

I’m really looking forward to seeing this one. I like paisley and I’m looking forward to seeing what you do with it.

Some shawl dresses do seem to have existed before the Josephine image – there’s this one in the V&A and I know Brighton Museum also owns another one of a very similar style, date and design

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O13819/robe-unknown/

Although of course, these are a different style to the Josephine one which obviously seems to have influenced all the others!!

Oh, thank you! I never realised that that dress/robe in the V&A was made from a paisley shawl. I did know Josephine wasn’t the first to wear one, but phrased that very awkwardly in my post, so it implies she was.

I’m not sure of the origins of the shawl used in the V&A dress – according to the description it’s a printed silk/wool blend so not in quite the same category as the other shawls above.

How exciting! I can’t wait to see this!

Laurie

I never knew the history of paisley and this post was an awesome little history lesson. I can’t wait to see your new dress!

I just reread the post and realized that the spelling of Kashmir changes several times. Why does the spelling change?

Kashmir is the place, Kashmiri is something from the place (e.g. a Kashmiri shawl is a shawl from Kashmir), cashmere is the fabric. Plus early 19th century Europeans used a number of different spellings for Kashmir – Chachimir, Cachmir, etc. Does that answer your question?

Wow, we’re on the same page! I’m working on a project that’s very similar: to wit, a Regency Paisley Fairy. I’m not 100% sure of all the details yet, but I’ve been researching a lot of this very same stuff!

Hi!

I can get you the exact Kashmiri shawl worn by Empress Josephine. I have a nonprofit organization working to revive the arts so handmade products in Kashmir. I would love to get in touch with you to see if we can on something together.

You did a fantastic job explaining the history of these beautiful shawls. Thank you.

And your work is phenomenal! A true master piece 🙂 keep it up.

Jenny Housego, a. British textile historian, and resident of Delhi for over 25 yrs. would likely be a good resource. She has a company called Kashmirloom.

I have come across some antique shawls on Rubylane.com at very reasonable prices.

Best wishes with your interesting project.

Jacky Shah