The Historical Sew Monthly 2018 is well underway now, and it’s my duty and honour to write the inspiration post for our fifth challenge of the year: Specific to a Time (of Day or Year).

I was slightly panicked when I realised this theme would fall to me. I’m not at all an expert at pre-1700s fashions, and this is a challenge that’s particularly tricky before the 19th century (ish), when specific garments for different times of day became common. But with help from my awesome co-moderators, I’ve found examples from a range of eras – enjoy!

In chronological order:

This ca. 1400 cycle of frescos of the months from the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento, Italy, provides a wonderful look at late Medieval fashions by season, with warm layers for winter snowfights:

January detail, Cycle of frescos of the twelve labors of the months, Trento (Italy), Castello del Buonconsiglio (Bishops Castle), Torre del’Aquila (Tower of the eagle), otherwise unknown Master Wenceslas of Bohemia, after 1397

Flowing garments for spring romance (note the love-knots on the gentleman’s tunic):

May detail, Cycle of frescos of the twelve labors of the months, Trento (Italy), Castello del Buonconsiglio (Bishops Castle), Torre del’Aquila (Tower of the eagle), otherwise unknown Master Wenceslas of Bohemia, after 1397

And sunhats and light shirts (and sandals!) for harvest labours. The sunhats do double duty for this challenge, being both daytime, and summer, specific:

May detail, Cycle of frescos of the twelve labors of the months, Trento (Italy), Castello del Buonconsiglio (Bishops Castle), Torre del’Aquila (Tower of the eagle), otherwise unknown Master Wenceslas of Bohemia, after 1397

Elizabethan costume plates also show wonderful examples of sunhats, like this charming bowl-shaped number.

Portraits are so formal it’s tricky to identify seasonal and time changes, but I’ll guess that heavy fur lined cloaks like the one sported by the Earl of Pembroke were far more popular in winter than summer:

Henry Herbert (1538—1601), 2nd Earl of Pembroke

And, while fans are a popular accessory for ladies in late 16th and early 17th century portraits, I can’t help but to suspect that they were even more common in the warmer months than at other times of years:

Elizabeth Stuart, Princess Royal (later, Queen of Bohemia), Robert Peake (1551-1626), 1603

Queen Christina of Sweden by Jacob Heinrich Elbfas, 1634

Going back to winter, we have the wonderful fur-lined jackets that appear in many Dutch interior scenes of the mid-17th century. This one gives the central figure a place to warm her hands, while also refusing to take the gentleman’s missive.

Gerard ter Borch II, The Letter, 1655

The advent of fashion plates in the late 17th century makes identifying seasonal specific fashions much easier. This elegant lady’s soft quilted hood, cozy quilted petticoat, and warm muff all seem perfect for winter, but the caption leaves no doubt at all about the seasonal-appropriateness of her dress:

‘Femme de qualite en habit d’hyver’ Nicolas Arnoult (France, circa 1671-1700) France, Paris, 1687 Prints Hand-colored engraving on paper, LACMA, M.2002.57.64

Her informal summertime counterpart, on the other hand, wears much lighter dress, and carries a fan. Although they are half a century later, the frequency in which fans appear in 17th century summer-themed fashion plates, and their infrequency in winter plates, makes it likely that the same seasonal shift appeared (or was at least starting to appear) earlier in the century.

Recueil des modes de la cour de France, ‘Femme de Qualite en Deshabille d’Este’ Jean LeBlond (France, active circa 1635-1709) France, Paris, 1682 Prints Hand-colored engraving on paper, LACMA M.2002.57.65

If the 18th century is your thing, you could make a bergere, suitable for summer, daytime wear from the 1750s onwards:

Bergere hat, English c1750, Royal Albert Memorial Museum

Princesse de Lamballe, 1782, Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun

(pictorial evidence suggests that chemise a la reine were primarily daytime wear, but I’ve found a few images that suggest they were also worn to nighttime events, so you’d need to make an argument for them being specific to a time of day if you wanted to make one for this challenge).

While chemise a la reine aren’t clearly for one time of day or other, and dresses like this could be worn to formal events at any time of day or year, masked balls were, as much as I can determine, purely nighttime events, so a masque would be a suitable item:

Anton Raphaël Mengs, Arabella Astley Swimmer, Lady Vincent of Stoke D’Abernon, 1753

Masquerade mask. 1780s © Museum of London via BBC Radio 4

Riding habits were daytime dress:

Collett, “Officer in the Light Infantry,” 1770

And fur line cloaks, and muffs of all description, were clearly cold-season accessories:

Elizabeth Farren (born about 1759, died 1829), Later Countess of Derby by Sir Thomas Lawrence (British, Bristol 1769—1830 London), 1790

Muff English, 1785—1800 England, MFABoston

As were quilted petticoats:

Caraco circa 1780, quilted Petticoat circa 1770-1780, Mint Museum

Leaving the 18th century behind, and moving into the 19th, the distinction between daytime and nighttime dress, and thus things that qualify for this challenge, becomes much clearer.

Short sleeved dresses were primarily evening appropriate in the early 19th century:

Full evening dress, June 1809, La Belle Assemblee

And long sleeves were daywear, as were, generally speaking, chemisettes and other neck fillers:

Portrait of a Lady (possibly Caroline Bonaparte-Murat, Queen of Naples) by Robert Lefèvre, 1813

While top hats were worn year round for men, there are some summer-specific versions in straw:

Straw as a summer specific material is a common thread throughout this theme, from the medieval examples we started with, all the way through the 19th, and into the 20th century.

Straw bonnet, ca 1880, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Winter hats, in contrast, came in dark colours, and furs and fabric:

Hat Mme. Mantel (French) Date- ca. 1885 Culture- French Medium- fur, wool, silk, Metropolitan Museum of Art

While the 18th century primarily had formal or informal clothes, rather than day and evening clothes, as the 19th century progressed the break between the two became quite rigid, though some robe a transformation dresses came with both low-cut, sleeveless evening bodices, and long sleeved, high necked, daytime bodices:

Dress in three parts, Italian, silk taffeta with straw embroidery, 1867, Galleria del Costume di Palazzo Pitti, 00000101, via EuropeanaFashion.eu

Dress in three parts, Italian, silk taffeta with straw embroidery, 1867, Galleria del Costume di Palazzo Pitti, 00000101, via EuropeanaFashion.eu

The growing power of the Industrial Revolution also made seasonal clothing distinctions even clearer. No longer was seasonality just about fabrics that were warm vs. fabrics that were cool, it also took in colours.

Coal powered machinery made industrial cities very dirty, and light clothes impractical. The advent of rail travel made getting away from cities easy – especially for the well off. They signalled their summer escape from hot, dirty cities by donning white clothes, and then put back on dark ones when they returned in the autumn, leading to sayings like ‘no white after labour day’.

Suit, 1875—90, British, linen, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.487a—c

Woman’s Polonaise Dress, England, circa 1875, Cotton plain weave with wool of discontinuous supplemental weft, silk satin ribbon, and machine lace, LACMA, M.2007.211.777a-f

Woman’s dress, American, 1905—10, Embroidered cotton with lace inserts, MFA Boston 2007.523

One of my favourite time/seasonal distinctions is when the same garment (by name) would be specific to very different times of day or season, depending on the design, and what it was made of.

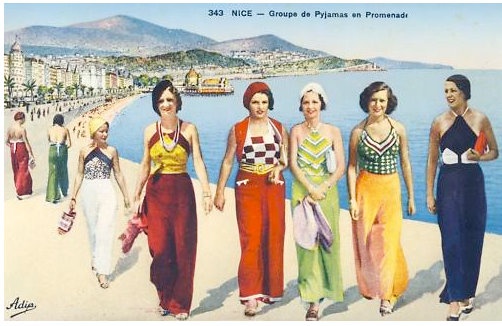

So, for pyjamas, we have beach pyjamas (daytime, summer)

Beach pyjamas on the Cote D’Azure, colourized postcard, 1930s

Evening pyjamas (nighttime, summer or winter):

Evening suit and blouse (or evening pyjamas), Chanel, 1937-38, collection of the V&A

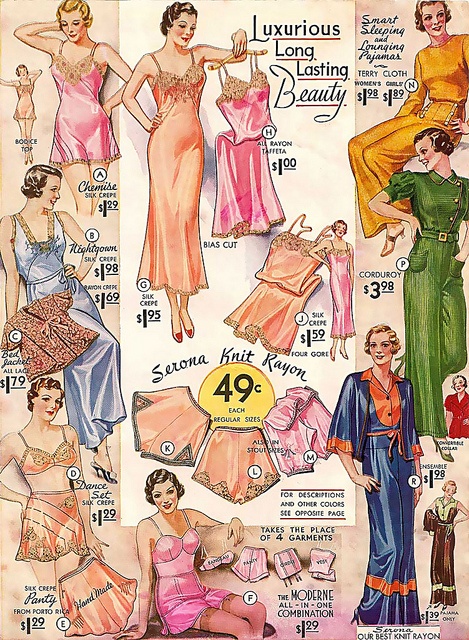

And lounging pyjamas (day to evening, usually winter), and pyjama pyjamas (nighttime, sleeping):

Pyjamas and lingere in rayon, 1934

Can’t wait to see what you make this is Specific to a Time!

This is the challenge I’m most stumped about, it helps to read through your post, but I still have no idea. I need to spend May finishing an 16th century outfit for first weekend of June, so it needs to be 16th century and a small project so I don’t take too much time from my main May sewing.

I adore the facial expression of the lady refusing the man’s letter!

The idea of changing clothes for different ‘seasons’ of the day is sometimes an appealing one, though you’d want to be sure of a warm room to change in during winter! But I suppose multiple outfits per day was the sole preserve of those who could afford to heat multiple rooms in any case.

These are great examples, and some of the clothes from the Castello del Buonconsiglio frescoes are really beautiful.

Oh gosh, I hadn’t even considered that a riding habit would “specific”. I’m plugging away at mine and fully expect to have it done in the next few weeks. Project finished and an entry? Double-win!

Hi,

I am from the Netherlands and busy making an exposition with caraco-jackets for women in the 18th century.

Do you know the history/explanation of the word caraco? We can’t find it till now!

Please let us know your answer(s)!

Gerda,

Leens, NL