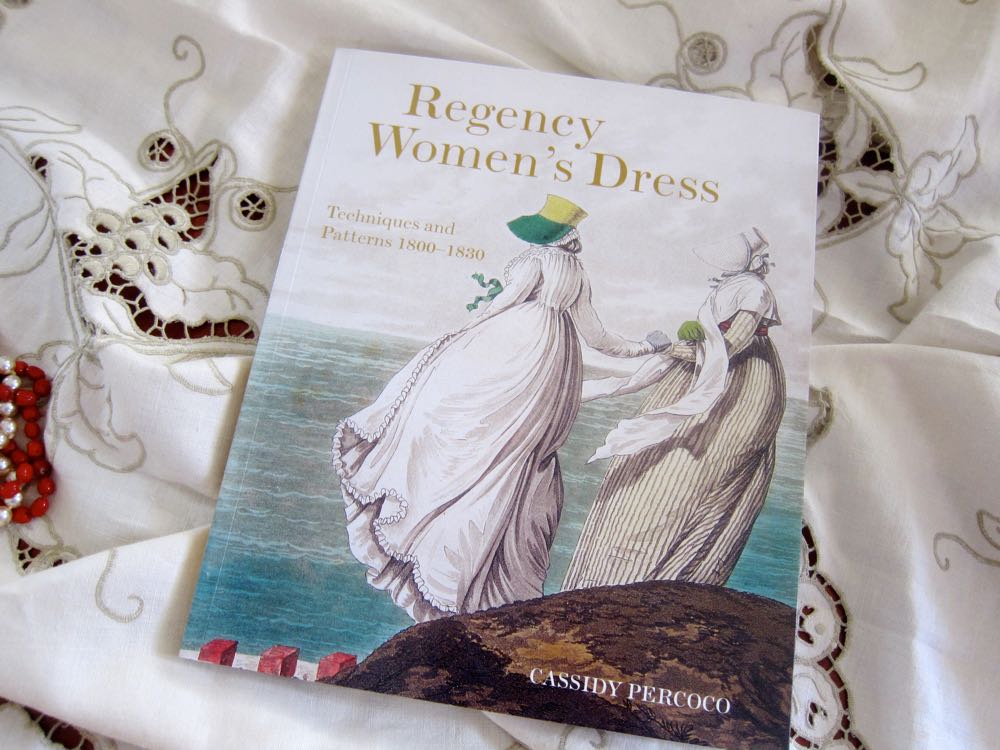

Last September I noticed that a new book on Regency fashion was due to come out at the start of October: Cassidy Percoco’s Regency Women’s Dress: Techniques & Patterns.

Exciting!

I’ve long thought that one of the things the historical costuming world is really lacking is a comprehensive book on Regency fashions. I’ve also felt that my personal historical wardrobe is sadly lacking in some good Regency pieces. Percoco’s book just might be the perfect answer to both needs!

So I added the book to my wish-list, and made a mental note to check it out once it became available in New Zealand, or browsable online (the overflowing state of my bookshelves combined with the high cost of buying books in NZ, or getting them shipped here, means I have to be really committed to a book before I can allocate it shelf space). And then the publisher wrote and asked if I would review the book for its Southern Hemisphere release. Yes please!

As it happened, that meant I got the book three days before Christmas, which is a terrible time to review books, because it’s too late for people to buy it as a present, and no-one is reading blogs anyway.

But the holiday’s are past, people are reading and ready to shop again, and I have had time to thoroughly peruse the book. So, ladies and gentlemen, a review.

The Good:

The book includes descriptions, sketches, detail images, and patterns for 26 garments representing women’s dress items from 1800 to 1827.

The garments are well chosen to represent the type of garments that a general re-enactor of the period would want, rather than focusing on more ‘interesting’ but less universally useful unusual garments, as Salen’s Corsets did. The patterns represent everything from chemises, two styles of stays, to dress for a variety of occasions from informal to formal.

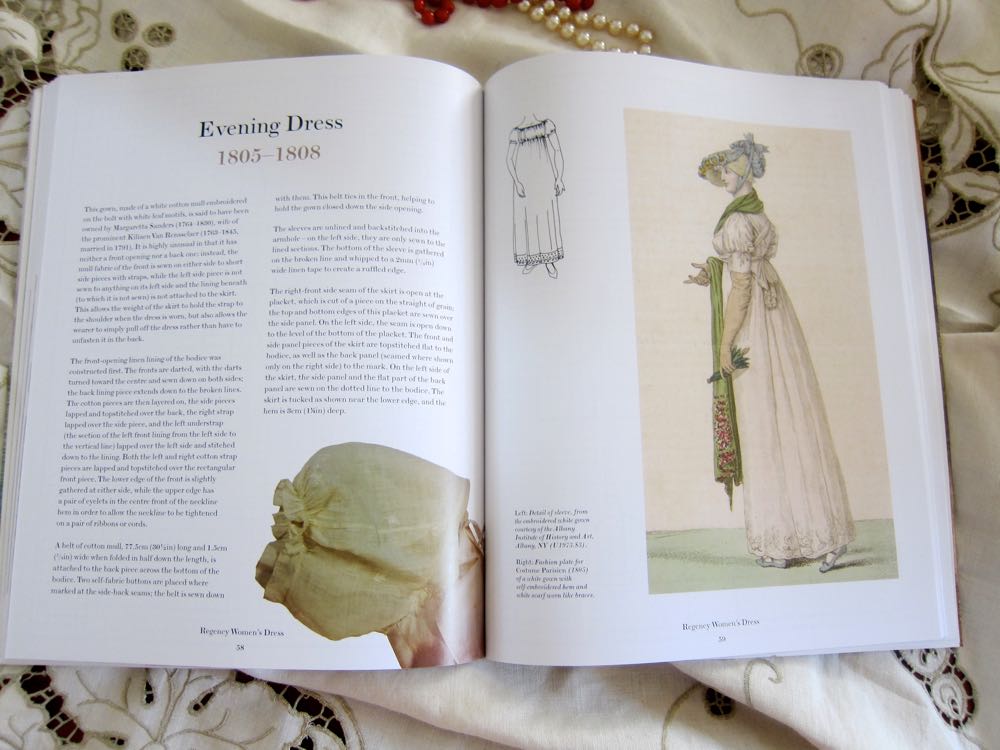

Each pattern comes with a overview of the garment, the type of event it would be appropriate for, provenance information when known, and the a general description of the construction details, giving a fairly extensive background into how to make and were to wear the garment.

The book begins with an excellent overview of fashions in the period 1790-1830, covering the different types of dress, changes in styles from year to year, and the basic stylistic differences between French, English & American fashions. I would disagree with Percoco’s concluding statement that “The fashions at the beginning of the nineteenth century signalled an enormous break with the dress that came before them, which had been almost unchanged in fundaments for the entire previous century.” as I can see a clear transition (rather than break) in styles from the 1770s into the 1800s, no more or less enormous or fundamental than the changes in styles from the 1710s to the 1740s. This aside, the overall description of Regency fashion is one of the most comprehensive I have read, and is quite impressive in both depth and breadth for its three-page length.

The ‘this could be good or bad, depending on your perspective’:

All of the garments in the book are drawn from collections of smaller museums in New York state. This makes the book an excellent resource for US re-enactors wanting to recreate the types of clothes worn by women in the East Coast of the US in this period, but slightly less useful for those outside the States wanting to replicate the fashionable dress of England or continental Europe.

The Bad:

Unfortunately there are a few definite drawbacks to the book.

First, there are no photographs of the complete garments for each pattern, just small detail images of a the fabric or a construction feature. This may have been done for reasons of space, as an aesthetic choice, for cost (perhaps the museums were asking very high fee licenses for full-garment images? ), or because too many of the garments were in too weak a state to be mounted for full display. There are sketches of the full garment that accompany each pattern, but they are quite simplistic, and show only one angle of the garment, leaving the reader to attempt to visualise the back or front based on the pattern pieces. The book would have benefited immeasurably from either full photographs, or very detailed technical drawings of the garments and some of the more intricate construction features, a la Janet Arnold or Norah Waugh.

Each garment does come with a period fashion plate to illustrate the style, but not all of the fashion plates are exact, or even close, approximations, of the garment depicted.

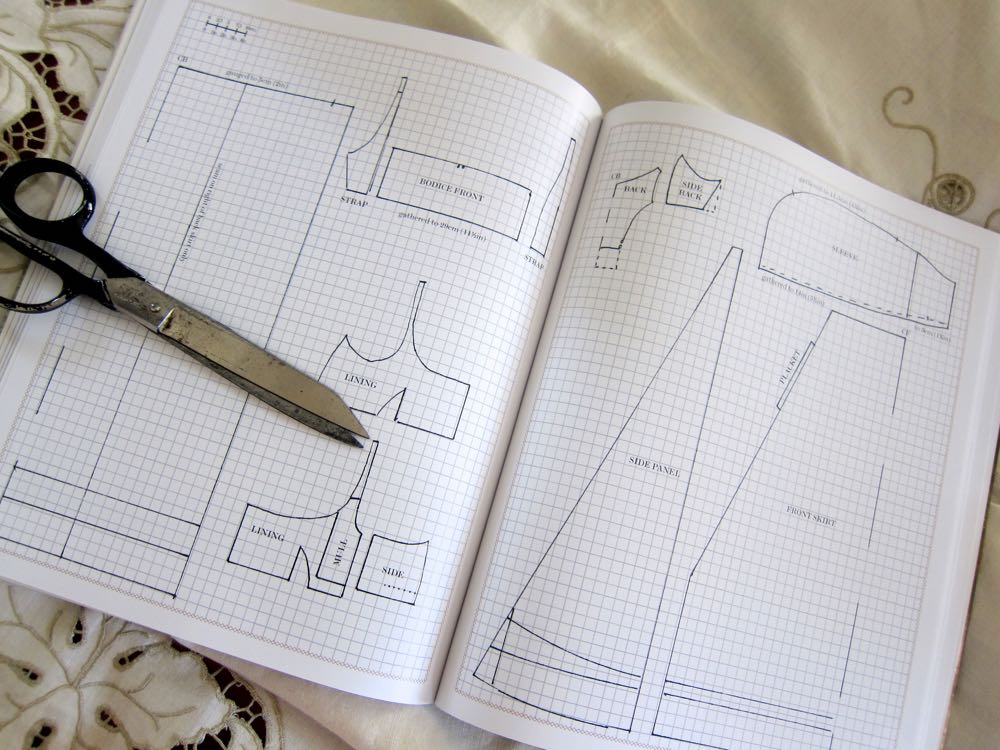

The patterns themselves are fairly simple hand-drawn patterns, and, while excellent for giving overall shape, would have benefited from a few more details in regards to decoration and trim.

The editing of the book is slightly rough in a few places, with the occasional confusing grammatical construction, and at least two typos, one of which is a fashion plate dated to c. 1903 rather than c. 1803. Rather unfortunate.

I would have liked to have seen a glossary or a bit more description of the fabrics used in each garment, to assist in reproducing. Most garment’s fabrics are mentioned, but it is never made clear that, for example, the silk crepe used in a Regency evening gown would be quite unlike the silk crepe one could buy today.

Finally, I felt the book was lacking slightly in the ‘techniques’ mentioned in the title. While the construction descriptions with each dress are nice, it might have been a better book with one less pattern, and a four-page description of basic construction techniques and stitches for one garment.

The Verdict:

The book is an excellent addition to the bookshelves of the dedicated multi-period costumers, or the specifically Regency re-enactors. The range of patterns given and the very helpful overview will be of great assistance in dating and recreating a whole range of looks and garments. Percocco certainly knows her period, and gives some very interesting insights into regional and dating differences that I have not encountered elsewhere.

If you aren’t that dedicated, or have limited space or budget, I’d probably recommend investing in Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion I, Nancy Bradfield’s Costume in Detail, or Norah Waugh’s The Cut of Women’s Clothes 1600-1930 first. Percoco’s book does have the distinct advantage of including patterns for almost every garment you might wish to wear, but the lack of detailed patterns, sketches, or full-garment images does limit its importance and helpfulness.

I find it hard to resist any book that has patterns taken from extant garments. 🙂 May I add a few thoughts to your excellent review?

When began to read my copy, I noticed that the front flap says “This practical guide begins with a general history […] and a description of construction techniques used by seamstresses of the period. This is followed by 26 patterns […] each with an illustration of the finished piece and an explanation of any deviations from standard construction.” Reading this, I thought it was great that the book would cover general construction techniques too, and was disappointed later when I found that there was no such section after all; just a bit about each garment (i.e., the “deviations”?). I assume a section on construction was planned to be included, but then omitted at some point during the process.

As a non-British European, I found it very interesting that the introduction says “there are certain stylistic divergences between Britain and France, in which American women tended to side with their French cousins.” So, these American garments may also be relevant for other places that had more French than British influence. Remember that virtually all of the extant garments in Arnold, Bradfield and Waugh are from British collections, and probably reflect British fashions. As far as I know, there are very few published patterns from Continental European extants (and I reckon Karl Köhler is a bit too early to be fully trusted).

I really appreciate that there are both metric and imperial measurements, which I didn’t expect in an American publication. Both are competently handled and the numbers are sensibly rounded.

While the lack of photos is disappointing, I find it really helpful how the well-selected fashion plates put the garments in context, styled with shoes, bonnet or hairstyle, and gloves or other accessories – a good starting point for an entire outfit.

Regarding the patterns, I did find some of the more complex gowns hard to assemble in my mind. Some of them have both lining and outer fabric, different seam placements in different layers, and sometimes gathering or overlapping, and it would’ve helped a lot if there had been letters or symbols showing how the parts fit together. In general, more information on the pattern pages would’ve been great. E.g., the three unnamed pieces in the middle of page 48 leave me completely clueless (possibly it’s the undersleeves and chemisette mentioned in the text). There are textual descriptions to some extent, but I think it would really have helped if more of the explanations were placed next to the pattern pieces they apply to (like Arnold did), instead of in the running text .

The lack of back views and more detailed pattern “instructions” sounds like a particularly vexing ommission.

And construction techniques. Is there a book anywhere that covers those? I feel like that might be the most glaring gap in available knowledge about historical accuracy.

I was so excited to read the comments on this post, with artisans more skilled and knowledgeable chiming in. Thanks, Anna-Carin!

Like Hana, I wonder if there exists some sort of compendium of construction. I also want to know all the WAYS that French/American/French were different. And while I can ascertain how 1770s became 1790, I have trouble telling the difference between 1710-1740. (or 1730s to 1770s, as I admitted in a comment to another blog post) What sorts of sources could I look at to find the answers?

Well, if you read Percoco’s introduction, it covers the differences in fashion between countries :-).

There is a bit of a dearth of knowledge around early 18th c fashion. Elisa of Isis’ Wardrobe has done a lot of excellent posts about it, but I shall add a post about changes in fashion in the first half of the 18th c to my (very long) blog to-do list.

Just looking at Janet Arnold’s patterns, and reading Waugh is also helpful.

Oooooooo….now to order from the library. Thanks for the tips, and looking forward to your blog…when you get the opportunity!

Thank you very much for this review. All I can say is that I want this book. I am still learning the basics of the craft, yet finding patterns with no illustration or example of what the garment should look like upon completion; is my favorite kind of Sunday puzzle. I tend to work in 1/4 scale as it saves money on fabric and I also collect dolls so someone can wear my mistakes and successes. While I have no clue about construction techniques used by anyone at anytime, I thoroughly enjoy fitting two pieces of fabric together to make something I can no longer walk into a store and buy.

I love your blog as you are both educational and inspirational. I will review my grammar, which is awful and I will seriously consider either ordering this book of forcing my local library to do so. Thank you!

I love your blog, and am grateful for all the time you put into it. I think I will be buying this book, as I’m about to undertake a costuming project for one of our sister-museums, and I’ve never made Regency before. I’m so excited! For your readers who are looking for more information on period sewing techniques, I have a few suggestions: Diderot has a variety of stitches, reasonably illustrated; Gerhet’s Rural Pennsylvania Clothing is great for showing the stitching in artifact garments, and giving diagrams to work from; The Workwoman’s Guide, although much later, gives loads of technical information that can be put into our context. These are the sources that I’ve used to build my stitching vocabulary. I’d be thrilled to find another!