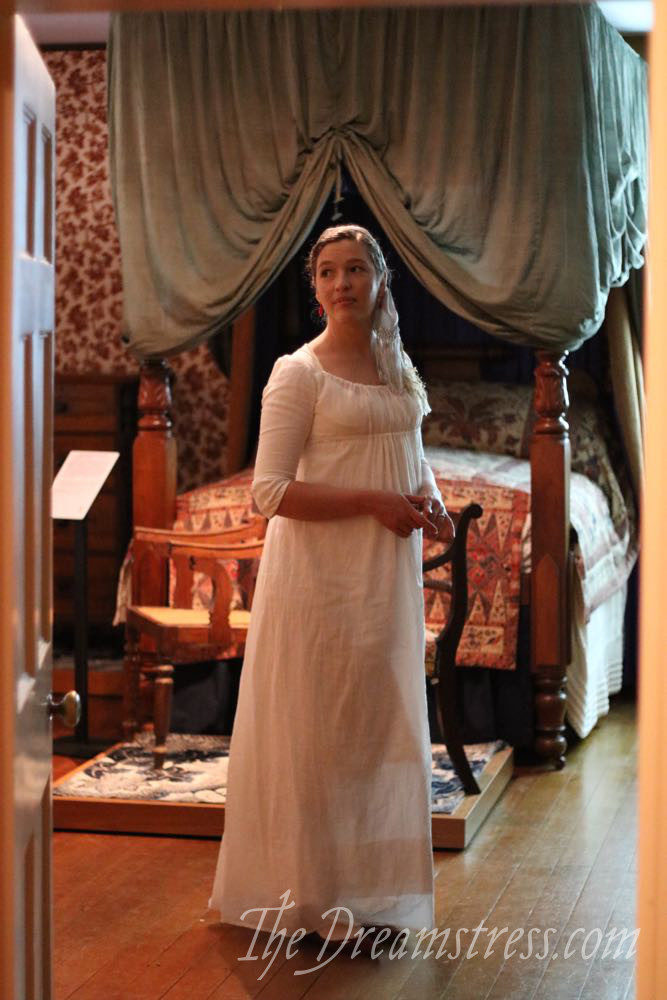

I was really excited about my trip to Australia, and an opportunity/excuse to make a new ca. 1800 dress.

I’ve done very little historical sewing since last Costume College, and I’m definitely missing it. Regency has been on my sewing wishlist for quite a while. I had a length of muslin I found at an op-shop that was just asking to be a simple almost-white dress.

Should be perfect!

Unfortunately I’m pretty meh about the result.

I’m not sure if it’s really the dress, or simply in my brain.

I’m currently going through a really hard patch as a costumer and historical sewer. Mentally, I need a certain amount of time to focus on a project in order to really do a good job. And I also need to keep in practice in order to not only to keep growing as a historical sewer, but to just stay at the levels of sewing that I’ve achieved in the past.

And for the last few years I just haven’t managed to make that time. Between starting Scroop Patterns, teaching sewing, buying+painting+repairing a house, blogging*, running the Historical Sew Monthly, and some big personal life stuff, I’ve had little space for large-scale historical costuming. There have been no more Ninons.

(*And you’ll probably have noticed that I haven’t been nearly as prolific at blogging as I was in the past…)

I’ve made a lot of great little things for the HSM, and my stocking and chemise stash is in pretty good shape, but full outfits? Impressive dresses? It doesn’t feel like it.

Emotionally I’m finding it really hard. I see all these other costumers making all this amazing stuff, and the few bigger things I’ve managed to make I feel like I need to totally take-apart and re-make to get them to where I want them to be. On a logical level, I know I’ve been doing an impressive amount of things over the last couple of years – they just haven’t been costumes. But emotionally my brain beats me up for not making as much as I think I should be able to, and not making them as well as I know I can.

I’ve been making some pretty big life changes that will hopefully give me a bit more time for costuming (though on a pragmatic level, I will be spending most of the extra time on Scroop), so that’s something to look forward to.

For now, I’m just trying to decide if I like this gown as it is, or if its another thing that’s going on the re-make pile. Or if I should just leave be and turn my energy to the next thing, even if I’m not happy with the dress as it is.

I’m not even sure why I’m so un-thrilled with this dress. I gave myself enough time to make it (just), and managed to make and finish it pretty much as I’d intended and hoped. The long seams are machine sewn, and everything else is hand-done and finished.

I didn’t get the back neckline quite right, which is causing some slight rippling along the neck seam. However, it’s easily fixable with a little more pressing and some stabilising stitching.

I also need to tweak the fit of the sleeves a tiny bit, but that is also easily fixable, and something I expected: I put the sleeves in without time to check their fit, and planned on adjusting them as needed.

I’m not entirely convinced by the bulk of back gathers.

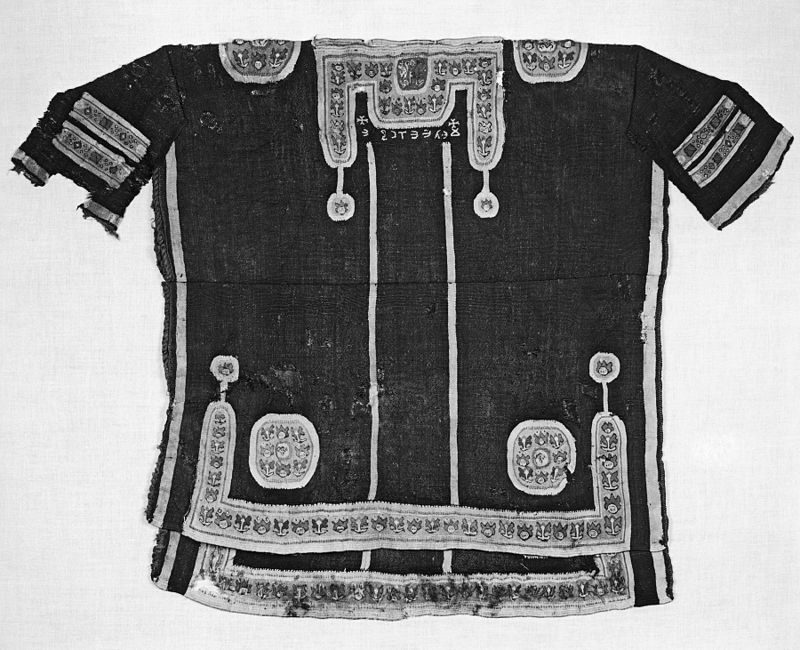

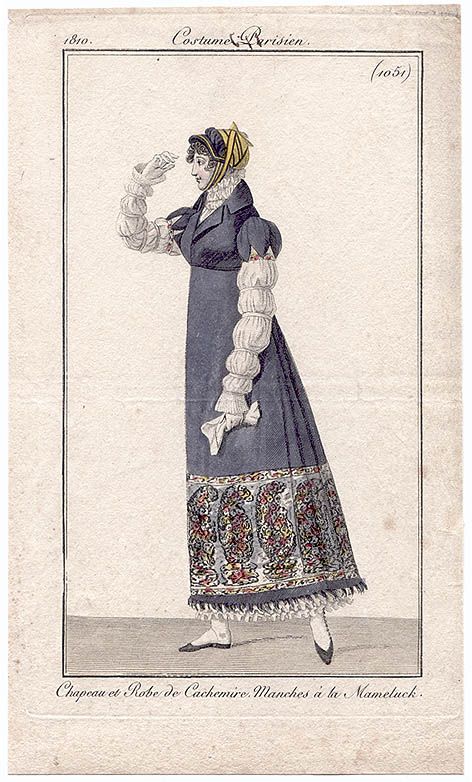

My base patterns was the silk 1795-1800 round gown from the Daughters of the American Revolution An Agreeable Tyrant catalogue. I made almost no adjustments to the bodice (I graded it up less than a size). When it came to the skirt, I used the pattern piece sizes, tweaked slightly to best fit my fabric, but I completely ignored the skirt pleating of the original. I just made the front fullness match that of the bodice, and gathered all the rest to match the triangle of the back bodice, inspired by portraits like this.

It’s fun, but it’s a LOT of gathers in one place.

Maybe my ambivalence is that the dress, while lovely, isn’t exciting or memorable.

Or maybe it’s that, as I was making it, I had a design epiphany. I was checking the fit of the bodice and realised the muslin is so sheer that it looked beautiful on its own over my skin. It would look beautiful as something like the dress in Lefèvre’s Portrait of a Woman Holding a Pencil:

Portrait of a Woman Holding a Pencil and a Drawing Book, Robert-Jacques Lefèvre (France, 1755-1830) France, circa 1808, LACMA, M.73.91

I didn’t have the time to re-make the dress to fit my new idea – and I wasn’t even sure it would work. It would have required turning it into a wrap-front dress (because there would be no way to get in and out of it otherwise), completely unpicking the skirt, and re-adjusting the fullness to accomodate the wrap.

I might still do it, but I certainly couldn’t in the last day before I headed of to Sydney – so I finished it as it was, and I don’t love it. Or at least I don’t love at this exact moment.

It is however, done, and making a thing is pretty exciting.

AND it qualifies for the June Historical Sew Fortnightly challenge: Rebellion & Counter Culture.

HSM #6 2018: Rebellion & Counter Culture

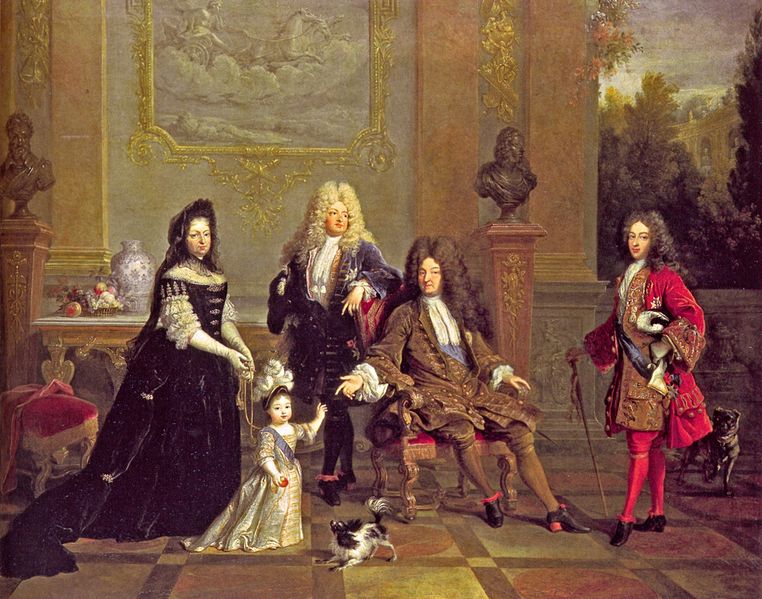

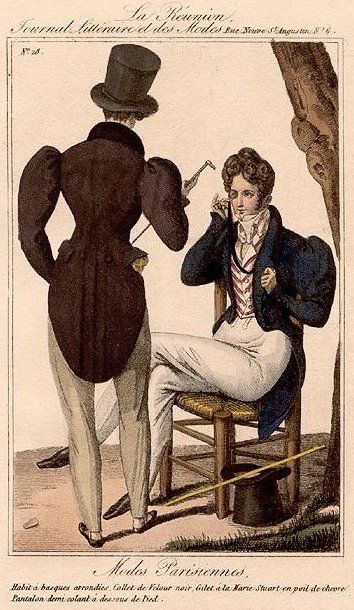

While simple cotton classically-inspired dresses were the predominant fashion of the last years of the 18th century, and the first years of the 19th, they were both a sartorial rebellion against the lavish silk gowns that were associated with the ancien regime, and later, against Napoleon’s attempts to support the French silk industry by dictating that silk dresses must be worn at court.

In Europe at least, they were most strongly linked with fashionable women who challenged societal standards, from Madame Recamier, to Lady Hamilton.

Because I was making my dress to be worn at a Regency era house in Australia, I tried to find a more local inspiration for it. I found a basis in a woman who was associated with a more political rebellion: Elizabeth Macarthur, wife of John Macarthur, who was responsible for instigating Australia’s Rum Rebellion.

While John was a bit of a loose canon and perpetual rebel, Elizabeth was so kind and charming and tactful that she was accepted everywhere, even when her husband was technically a criminal in exile. Elizabeth was the first soldier’s wife to arrive in the infant Sydney, and ran her husband’s farms on the (numerous) occasions he had to flee Australia because of legal troubles.

Her ability to retain respect, and remain in control in spite of adversity, could be considered a counter-rebellion: using tact and helpfulness to change a situation, instead of the open rebellion her husband favoured. I felt this modest version of a ca. 1800 frock was both suited to the New South Wales climate, and to descriptions of Elizabeth as quietly elegant in her dress.

Just the facts ma’am:

Material: 3.3m of cotton mull, 1m of linen

Pattern: primarily based on the late 1790s bib-front gown in An Agreeable Tyrant, with the quirks from altering the dress from an older style removed, the front adapted to be a round-gown instead of a bib-front, and the back pleats changed to gathers.

Year: ca. 1800 (keeping in mind that Australia would have been slightly behind the times in terms of fashion)

Notions: cotton thread, cotton tapes

How historically accurate is it? I machine sewed the long skirt seams, and made my best guess as to how a round-gown would be adapted from the pattern. My armscye seam finishes are based on Modern Mantua Maker’s 1800s gown which she made based on one of the Agreeable Tyrant dresses – her research is impeccable, so I trust her when she says this is an accurate finish, but I did not do the research myself, and have never seen the technique on an extant garment. Because I can’t verify all my techniques, I’d say 70%

Hours to complete: 20-30

First worn: Sat 26 June, to give a talk about the Indian influence on Western fashion for the National Trust of NSW, and then for a photoshoot at Old Government House, Parramatta. Elizabeth Macarthur almost certainly visited OGH, and was friends with Elizabeth Macquarie, the Governor’s wife, despite their husband’s mutual enmity.

Total cost: I found the mull at an op-shop for $4 (!!!), and the linen was also an op-shop purchase, so the whole thing cost less than $10.