The fourth Historical Sew Monthly challenge of 2016, due by the end of April, is Gender-Bender. In this challenge you should make an item for the opposite gender, or make an item with elements inspired by the fashions of the opposite gender.

The first option in the challenge is easy: if you have someone of the opposite gender to sew for, or an excuse to make something historical that was traditionally worn by the opposite gender for yourself.

Personally, I’ve always hankered for my own pair of 18th c breeches. Maybe even in leopard skin print…

Interior with three men, seated woman and a dog, Venceslao Verlin, 1768

The second option is significantly more complicated. On the surface, it seems simple. There are dozens of instances of clothing inspired by the fashions of the opposite gender.

The fashion for slashing that emerged in the later 15th century and lasted into the first few decades of the 17th, is generally attributed to the actions of the Swiss army in the aftermath of the Battle of Grandson in 1476. The Swiss supposedly celebrated their victory over one of the biggest powers in Europe, and symbolically revenged themselves on them for the deaths of their compatriots, by despoiling the lavish textiles the Burgundians had left behind, slashing them and using them to patch their own clothes. The story may not be completely true: there are examples of slashing that predate the battle, but it appears in contemporary accounts, and women who wore the style may have felt they were borrowing the strength and styling of the ascendent Swiss military.

Elisabeth of Austria (1554—1592) Queen of France, by François Clouet (1515—1572)

In the 18th century militaria was out, and leisure sports were in, particularly hunting. Ladies copied the jackets of men’s riding habits detail for detail in their own riding attire, and it was not unknown for them to borrow even the breeches. Both Marie Antoinette and her irreproachable mother-in-law were known to wear breeches for riding.

Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, the later Queen Marie Antoinette of France, at the age of 16 years, 1771

In the 19th century, the Napoleonic wars made militaria fashionable once again, and trimmings influenced by various military uniforms, particularly that of the Hussars, was seen on women’s riding habits, spencer jackets (which originated as a men’s jacket) and other day wear, and even evening dress.

Riding habit of green wool, circa 1825. From the Rijks Museum.

Dress (bodice detail), ca. 1818, British, silk, Metropolitan Museum of Art

As the 19th century progress, and the navy became more and more important as a military arm, naval inspired uniforms became more common and fashionable for women, sported by everyone from the Princess of Wales to lower-middle class girls.

Princess Alexandra in a sailor suit, 1880s

Princess Alexandra’s jacket demonstrates another form of gender-bending: the blurring of lines between the dressmaker, who did soft-fabric sewing and draping, and the tailor, whose more structured craft had traditionally been the male prerogative. As the 19th century progressed more and more women’s clothes were made by tailors, and more dressmakers incorporated tailoring techniques into their work

Jacket and skirt, Great Britain, Uk, ca. 1895, Superfine wool, trimmed with velvet and braid, metal, lined with silk and glazed cotton, boned, Victoria & Albert Museum, T.173&A-1969

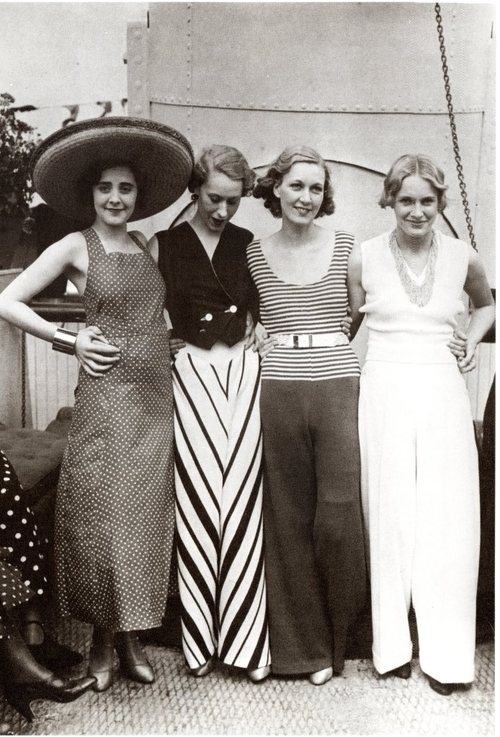

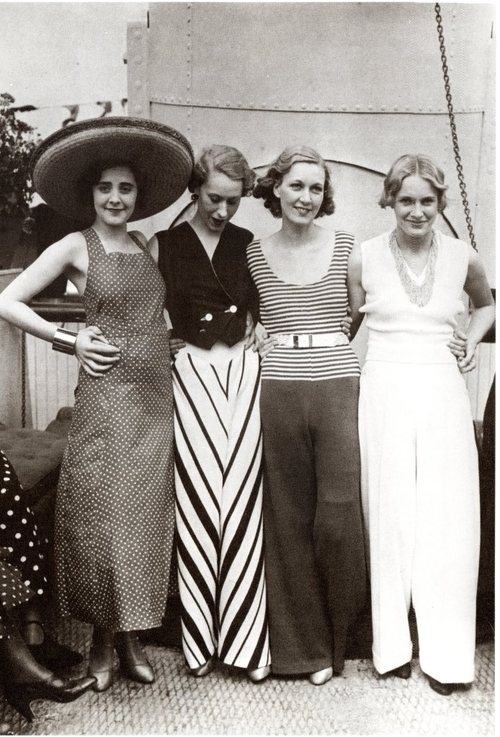

In addition to being more tailored, women’s clothing also became more practical and less about showing conspicuous consumption and enforced ornamentalism, culminating in the widespread adaption of the standard collared shirt and knitwear in the 1890s, and trousers as an acceptable form of dress in the 1920s & 30s.

Beach pyjamas, ca 1930

Notice a theme in all of these? All these examples of gender bending are examples where women’s fashion borrows elements of mens fashion. There are very, very few examples where men’s fashion borrows elements from women’s fashion (the only one I can think of that could plausibly be argued for is the Brummel bodice).

The reason? Historically, men have been seen as superior, and their dress was thus superior. Women borrowed men’s fashion because it meant they were adopting a position of strength. Men didn’t borrow women’s fashion, because while would they take on something that represented weakness? Society tolerated women borrowing men’s styles, though there were inevitably complaints about it, because it did not challenge the status quo: it reinforced the idea that what men did was to be emulated and admired. Society has long frowned upon men adopting women’s attire in anything but mockery, because it opens up a dangerous Pandora’s box of a question: if the way women dress is to be emulated, is there anything else that women do that is better than what men do, and should be taken up?

While clothing has become less gendered, and society more balanced, this attitude still persists in many insidious ways. ‘Androgynous’ styles that appear on the catwalk, and filter down to plebeian fashions, are predominantly based on menswear, and are adopted by women, who end up looking more like men – the desired look is still masculine. In the West, it’s generally acceptable to be a woman who doesn’t own a dress or a skirt, but is considered extremely weird for a guy to wear a skirt (other than traditionally male ones like kilts), even though I would definitely argue that there are situations and climates where it is more comfortable and practical to wear a skirt than shorts or pants. ‘Gender neutral’ children’s clothes aren’t really gender neutral. They are boy-friendly clothes, with the more overtly masculine imagery toned down, so that they are acceptable for girls as well as boys. They come in shades of blue, but never, ever, shades of pink. ‘Gender neutral’ children’s clothes include trousers and shorts, but never, ever skirts. When we give them to kids to wear we are telling girls that it’s good to be like boys, but we certainly aren’t telling boys that it’s good to be like girls.

Even examples of historical menswear that look feminine to us, weren’t considered feminine at the time: 18th century men’s waistcoats embroidered in delicate vining flowers just advertised that the wearer had the wealth to pay for silk, and to live a leisured lifestyle – admired attributes in a man at the time. ‘Little Lord Fauntleroy’ outfits for boys look ridiculously girlish to the modern eye, but Burnett’s novel makes his ‘manly’ looks explicitly clear, and the novel was actually responsible for the decline in dressing small children in gender-identical outfits, as even tiny boys were put in the breeches of the suit.

Gender-bending is fascinating, but it also reveals some unpleasant truths about our society, and how far we have to go to reach gender-equality.