Wearing History has an fabulous new pattern out and I am extremely excited about it 1) because it’s a kind of pattern that I’ve really wanted for a long time, and that is going to make my life a lot easier, and 2) I got to be a pattern tester! (yay!).

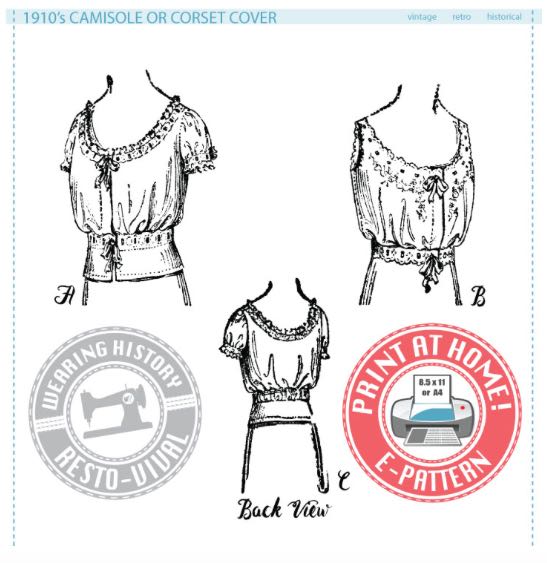

Wearing History’s 1910s Camisole & Corset Cover pattern has a low scooped neck back and front, slight fullness at the front and is suitable for wearing under or over a corset for all 1910s styles. It can be made with or without sleeves, and with or without a peplum.

I’ve really been getting into 1910s fashion, but my 1900s and 1910s camisole pattern (taken from an extent garment) is really skimpy, with tiny straps. It doesn’t provide enough coverage to wear under the sheer blouses that were fashionable in the 1910s (yes, really!), is too delicate to be made into a 1900s ruffle-fronted camisole, and can be a bit revealing for models in 1910s underwear when I do talks. So a 1910s corset cover pattern has been high on my wish list, and this one is perfect!

As a pattern tester, I felt I should do as many of the options as possible, so I made the version with sleeves and peplum:

I was a bit dubious about both these options, because I’m not always the biggest fan of teeny puffed sleeves and peplums, but once I had finished the camisole I decided that I actually really LOVE them. The sleeves are adorable, and the peplum is perfect for helping the corset cover to sit neatly under a 1910s skirt, like my Wearing History 1916 skirt.

While I loved the sleeves and peplum, I had so much fun making the first camisole (some sewing patterns are great because you are so pleased when you finally finish them, and some are actually properly a delight while you make them – this was definitely the latter! It sewed up in a couple of hours, and had so many techniques that are just fun to do!)) that I immediately cut out the sleeveless, peplum-less version to try it.

I made both versions quite plain and simple, with the recommended beading lace, but white ribbons, and no extra embroidery and embellishments, or fancy do-dads like hidden buttons, to make them as versatile as possible.

One of my favourite things about the pattern is that it comes with a TON of period illustrations of similar garments so that you can use them as inspiration (I’m definitely doing insertion next time!). There are also whole page excerpts from period sewing manuals on how to sew camisoles, so you can try alternative period accurate sewing methods to construct your own camisole. The pattern gives very complete instructions, but there are always multiple ways to sew any garment, and it’s fascinating to see all the different options that were available in period.

I made a few small deviations from the official pattern instructions to the period excerpts, simply because some of the instructions in one of the period manuals was how I usually construct a garment like this, so it made sense to follow that.

The only other major change I made to the pattern was to carefully check the armband and waist measurements – I ended up using my bust size (36″) for the main body pieces and sleeves, but going up to the waist and armband sizes for a size 38″ bust, and having slightly less gathers. It worked perfectly, and I’m really happy with the finished fit.

While the pattern is from the 1910s, it’s very similar to 1900s camisoles and corset covers, and would do nicely for that era. It shouldn’t be too hard to add a front full of ruffles, if you want to do the extremely full pigeon-breast thing, or to simply give it a slightly fuller, droopier front.

It would also be very easy to add a skirt a skirt to the bottom of the camisole, using the peplum or a general skirt pattern as a guide, to create a full petticoat slip/chemise, like these ones (or the really adorable examples given in the pattern pack) :

Don’t forget the lace insertion, ruffles, pintucks, and apricot satin bows!

If period isn’t your thing, Lauren at Wearing History has also made a version in fashion fabric to wear as a summer blouse, and I can definitely see myself doing that next summer.

All in all a great pattern – very well thought out, well put together, easy to follow, with lots of fun learning perks in the additional info (I LOVE a pattern that you learn from!), and a useful, versatile addition to my period pattern collection. There will be more!