The theme for the Historical Sew Monthly 2015 Challenge #2 is Blue: make something in any shade of blue.

I knew it would be a popular colour challenge choice because blue is simply the most popular colour: it’s more peoples favourite colour than any other.

Historically, it’s also been one of the most desirable colours in many historical periods and cultures, because the dyes used to achieve it were comparatively expensive and finicky, and the harder something is to achieved, the more expensive it is, and the more people want it.

In addition to being an expensive dye, blue acquired even more cachet in Europe in the Middle Ages when it became the colour associated with the robes of the Virgin Mary in devotional art. Mary was painted in blue robes partly because blue was the colour of the heavens, but mostly because the most expensive paint available was ultramarine blue. Mary was deemed worthy of only this rarest hue, this colour ‘from beyond the seas’, so was depicted in blue robes, often highlighted with the only colour more valuable than ultramarine blue: pure gold.

Mary’s robes probably wasn’t meant to correspond to a specific existing fabric dye colour, but a range of beautiful blues were achieved in Europe from at least the Iron Age, and throughout the Middle Ages with the plant dye woad (Isatis tinctoria).

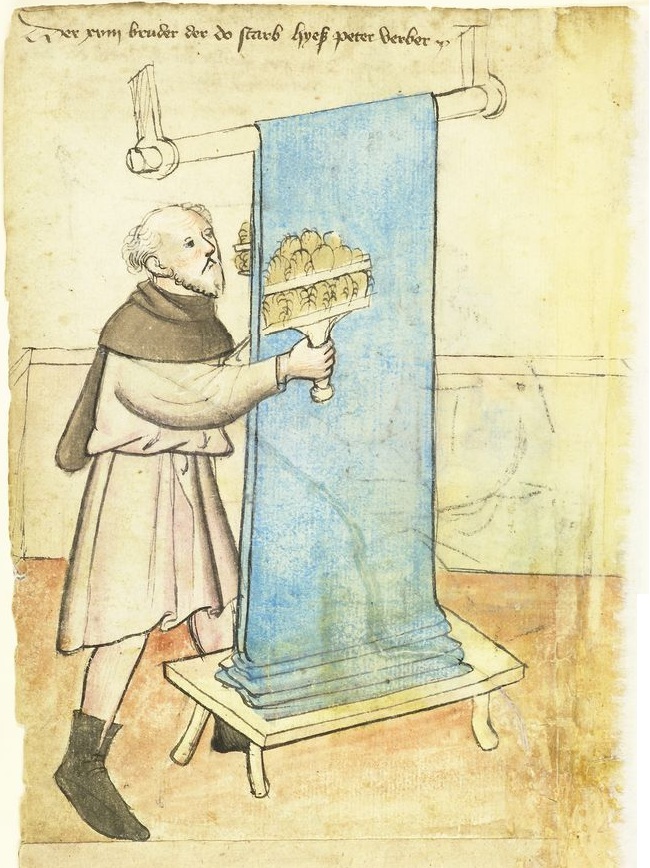

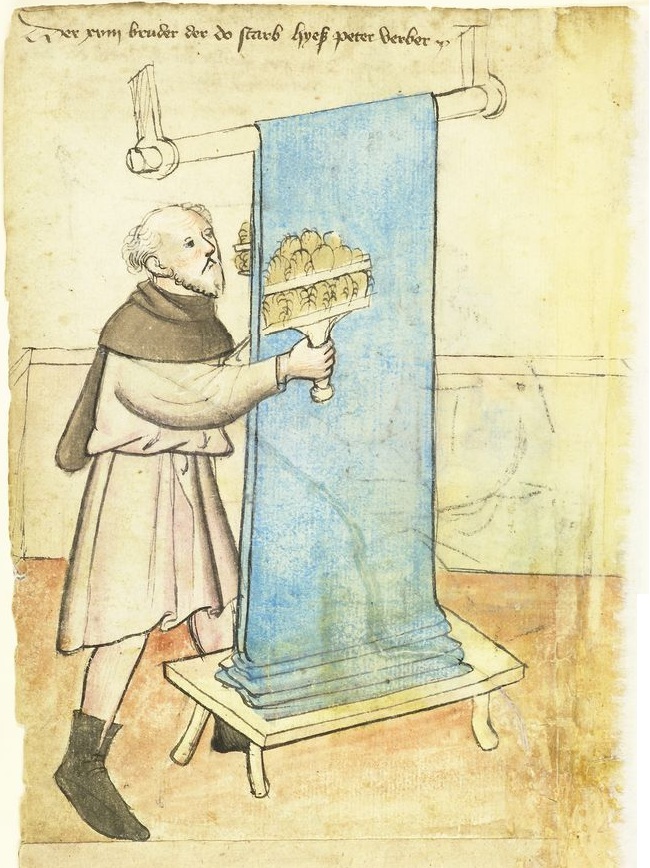

Mendel Hausbuch, f. 6v, c. 1425, Peter Berber, Carder brushing woollen cloth with teasel heads

Woad was one of the cornerstones of the Medieval and Renaissance dye industries, and whole towns grew, and grew rich, around growing and processing woad.

Mary Magdalene from the Braque Family Triptych (right panel), ca. 1450, by Rogier van der Weyden (early Flemish, 1399:1400-1464)

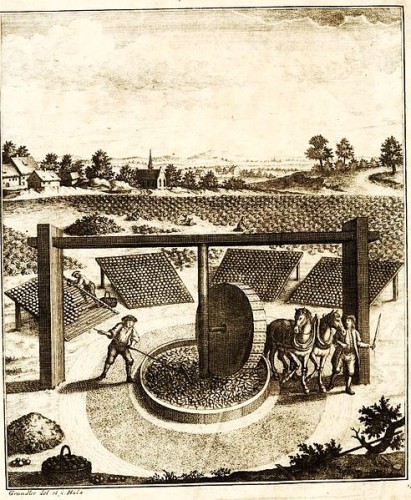

The problem with woad as a dye was that it takes a great deal of woad to dye a small amount of fabric – and the richer the blue that was desired, the more woad that was needed. So when European traders established sea trade routes to India in the 15th century and discovered Indian textiles dyed with the ‘true’ indigo plant (Indigofera tinctoria), which has the identical dyeing chemical (indigotin) as woad but at a much higher concentration, and so thus dyed the same range of blues, but with less plant needed to achieve them, they thought their fortunes were made.

Indigo plant, Molokai, Hawaii

Seeds and flowers of the Indigo plant, Molokai, Hawaii

Indigo was a novelty to European traders in the 15th century, but it wasn’t the first time it had reached Europe. The Romans had dyed fabric with indigo imported from India, but the decline of the Silk Road trade had made it a rarity in ensuing centuries.

The Cupid Seller – fresco from Pompeii, now at the Getty

As traders began bringing indigo dye back to Europe in the 15th centuries, governments realised the devastating effect it would have on their local dye industries, and took steps to discourage people from buying indigo dyed products, or dyeing with it. Indigo dye was dubbed ‘the devils dye’. Official edicts were issued warned that the dye was corrosive and would rot fabric. When warnings weren’t enough, stronger steps were taken. In 1577 indigo dye was officially prohibited in parts of what is now Germany. France, in 1609 called it “the false and pernicious Indian drug”, and forbade its use.

Chopines, 1590-1610, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Despite the prohibitions, there was no stopping progress. It was impossible to tell if a fabric had been dyed in indigo or woad once it was dyed, so indigo dyed fabric, or fabric dyed with a mix of the two dyes, became more and more common across Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially as more cotton fabrics, which required more dye than wool to colour, were imported from India.

In the 1750s the usefulness of indigo dye combined with the novelty of cotton fabrics and a newly developed technology: engraved copperplate printing, developed in Ireland in 1752, to create a classic textile look: the blue engraved-printed on white design. Known as ‘China Blue’, for it’s resemblance to blue and white porcelain, the resulting fabric was known for lighter blues on light grounds, as the process could not produce dark blues. The most notably example of the look is the fabric known as ‘toile de jouy’ look, after the town in France that produced the fabric with little pastoral scenes scattered across the fabric (though this fabric was rarely used for garments, with vining florals being much more common).

Gown, blue floral pattern on cream ground. 1760-1790, Copperplate printed linen. Worn by Deborah Sampson, possibly as her wedding dress. Historic New England, 1998.5875

Engraved printing, unlike the earlier woodblock printing, could produce fine, detailed designs, but only in one colour. Indigo blue was one of the most durable available dyes suitable for engraved printing, and combined with bleach innovations which kept the fabric very white, made blue and white combinations one of the most popular.

Pocket, printed cotton & linen, 18th c, American, MFA Boston, 48.1218

Indigo production had its dark side: when England took over India indigo was such a desired commodity that huge plantations were established to grow it. The native workers on the plantations were essentially slaves, and British indigo plantation owners had appaulling track records. The terrible conditions led to the 1859 ‘Indigo Revolt’ as workers attempted to better their conditions, but without much effect. In 1860 a native writer commented

“We have nearly abandoned all the ploughs; still we have to cultivate indigo. We have no change in a dispute with the Sahibs. They bind us and beat us, it is for us to suffer.”

There were also indigo slave plantations in the Americas in the 18th century.

Despite the revolts and the growing movement against slavery in the West, the popularity of indigo as a dye kept cultivation high. In 1897 it is estimated there were at least 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) of indican-producing plants (mainly true indigo) under cultivation. Most of these acres were in in India, and most of them were cultivated under horrific conditions.

What revolts and human rights campaigns couldn’t change, innovation could wipe out in a few short years. The discovery of aniline dyes in the late 1850s opened up the possibility of a cheaper chemical alternative to natural indigo. The first aniline dye was purple, but in the 1860s Nicholson’s blue (a vivid teal blue), bleu de Lyon, bleu de Paris, Britannia violet (a deep blue) and other bright shades of aniline blue were produced.

Child’s cape. Twilled peacock blue woollen cloth, embroidered in cream silk thread, with a cream tassel on the hood; Anglo-Indian, 1860-70, V&A

However, none of these were comparable to indigotin in the range of shades they could produce. Every chemist working with aniline dyes attempted to synthesize a synthetic indigo dye, but it wasn’t until 1897 that a commercially viable process was developed. This process, however, was so successful that it almost wiped out the natural indigo industry.

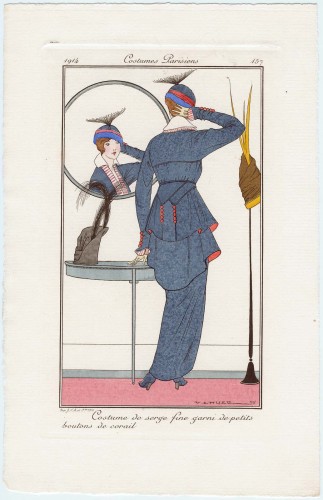

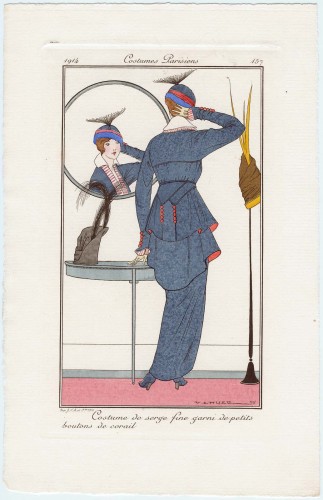

Costume de serge fine garni de petits boutons de corail, plate 157 from Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1914

By WWI almost all blue dyed fabrics were produced with synthetic dyes, though there was a very slight resurgence in natural dyes in both WWI and WWII, as the chemicals used in synthetic dyes were required for the war effort.

For more blue inspiration for the Blue challenge, check out my Blue pinterest board (which works its way from the present to the past as you scroll down the board. I’m only up to the mid-18th century as of the writing of this post, but there should be more recent stuff soon)

Sources:

Balfour-Paul, Jenny (2006). Indigo. London: Archetype Publications. ISBN 978-1-904982-15-9

Finlay, Victoria. Colour: Travels through the Paintbox. London: Hodder and Stoughton. 2002

Garfield, Simon. Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour that Changed the World. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 2000

Watt, Melinda. “Textile Production in Europe: Printed, 1600—1800 “. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000—. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/txt_p/hd_txt_p.htm (October 2003)