I love paisley (the design) and the history of Kashmir shawls. The interaction between the paisley design and Western fashion is fascinating, with both elements impacting the other in equal fashion.

Kashmiri shawls were first introduced to Europe in the late 18th century by English traders who had encountered them in India. In India the shawls were worn by men, but in Europe they were taken up by women as the perfect warm wrap to accompany to new light muslin dresses. The cashmere wool was lighter, softer and warmer than anything available in Europe at the time, and the paisley patterns were deliciously exotic to Western eyes. Kashmiri shawls were also the perfect status symbol – they were extraordinarily rare, and prohibitively expensive.

As with anything rare, expensive and incredibly desirable, those who could afford it flaunted it, and those who couldn’t scrambled to find a cheaper alternative. Manufacturers in Europe almost immediately began to replicate paisley designs (the name paisley comes from Paisley in Scotland where many imitation Kashmiri shawls were made) on wool-silk blends and on cotton, and even in India fakes were made.

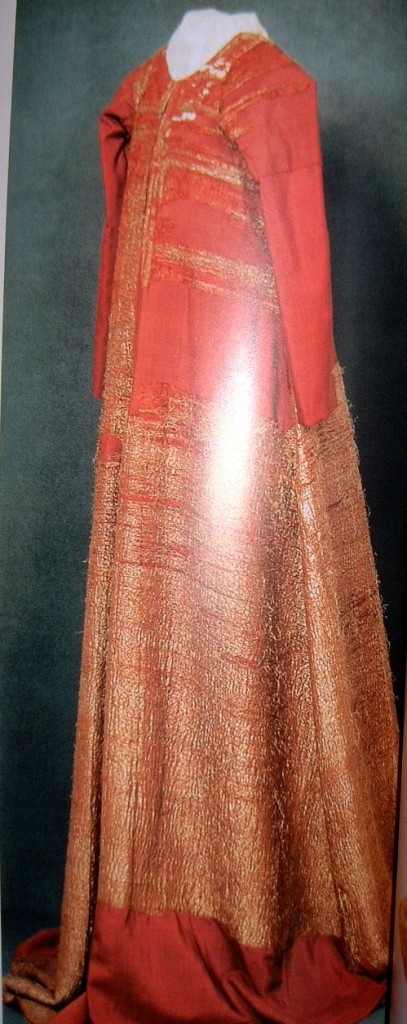

As the fashion for Kashmiri shawls spread and the importation of real Kashmiri shawls and manufacture of replicas made them more common the design moved beyond shawls, and paisley motifs were seen on dresses and cloaks. Sometimes these items were made from actual shawls (Kashmiri or European), and sometimes they were made from fabric specifically woven with paisley designs.

The ever fashionable Josephine de Beaunharnais, then Empress of the French, was certainly the most famous person to wear a paisley shawl. Gros painted her wearing a very simple tunic dress made from a Kashmiri shawl (this being Josephine, we can be sure it is real) over another dress, and a shawl as a shawl.

Empress Josephine by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, ca. 1808, Musee d’Art et d’Histoire at Palais Massena, Nice France

The artist Robert Lefèvre loved the look and painted two different noblewomen in dresses made from Kashmiri shawls, though as the poses and dresses are identical down to the last fold we can assume that Salome’s frock probably owes more to the artists imagination than anything the Comtesse actually had in her wardrobe.

Élisabeth Alexandrovna Stroganoff, Countess Demidoff (1779-1818) by Robert Lefèvre, ca. 1805 Hermitage Museum St Petersburg

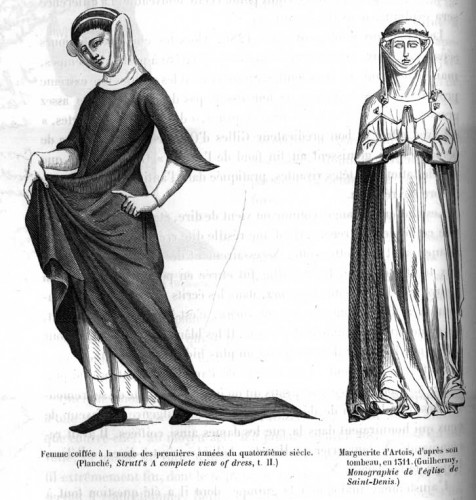

Fashion plates noticed the trend and disseminated it further.

Dress with paisley design, 1810

Not all frocks were made from real shawls. This frock is of red net over a white undergown with a paisley border, creating the effect of a Kashmiri shawl gown without the weight and warmth.

This gown also uses an fabric which gives the effect of a paisley shawl, and echoes the daring neckline of the Lefevre portraits on a more modest scale.

Evening dress, 1815, cotton & silk, Snowshill Wade Costume Collection, Gloucestershire

The next one is much less sophisticated in its silhouette and construction. The narrower, stiffer paisley design at the hem of this frock is purely European in creation, demonstrating how quickly the design was picked up and adapted in the West.

And not all paisley garments were dresses, as evinced by this charming cloak made from a paisley shawl.

The height of the Kashmiri-shawl-as-a-dress fad was from 1805-1815, but examples were seen into the 1820s, as evinced by the famous Amelie Augustes (her frock was the only 10 out of 10 Rate the Dress ever).

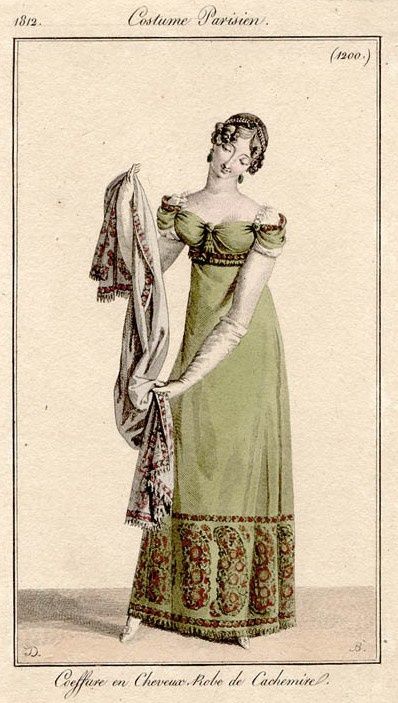

So what does this have to do with me? Well, my project for the Historical Sew Fortnightly Bi/Tri/Quadri/Quin/Sex/Septi/Octo/Nona/Centennial Challenge will be an 1813 Kashmiri shawl gown inspired by this fashion plate from 1812:

I figure that a wool or cashmere dress would be worn in winter, so if this was made in winter 1812, it would certainly have been worn in Jan 1813 – if not for years later. And, of course, women further from Paris and London could wait for months to get the latest fashion plates. I’m having to tweak a few things to fit my fabric, but based on the extend dresses compared to plates, that’s perfectly historical!

I’ve been making very good progress on it, and am so excited about the project! I’ll be showing you my work-to-date shortly.