After years of making do with bun rolls, and bumpits, and pads made from old hairpieces, and ad-hoc hair supports made from stockings, I’ve really gotten into historical hair-pad making in the last 8 months.

I’ve been experimenting with different patterns for 18th century and Edwardian hair pads (or ‘rats’, as they were called in the late 19th and early 20th century), and using different stuffings and outer fabrics.

Patterns

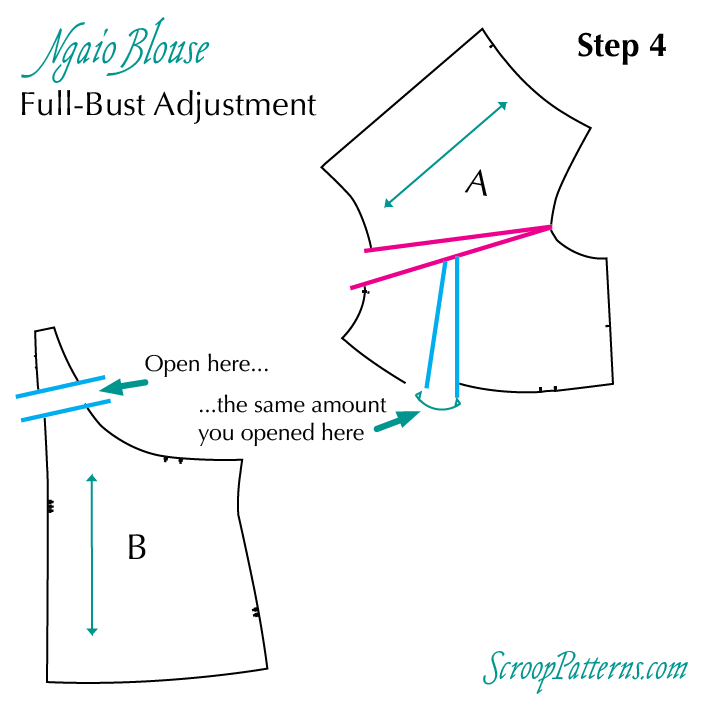

For 18th century patterns, I’ve mainly been using the American Duchess book, and adjusting the size, shape, and pleat arrangements to get different effects.

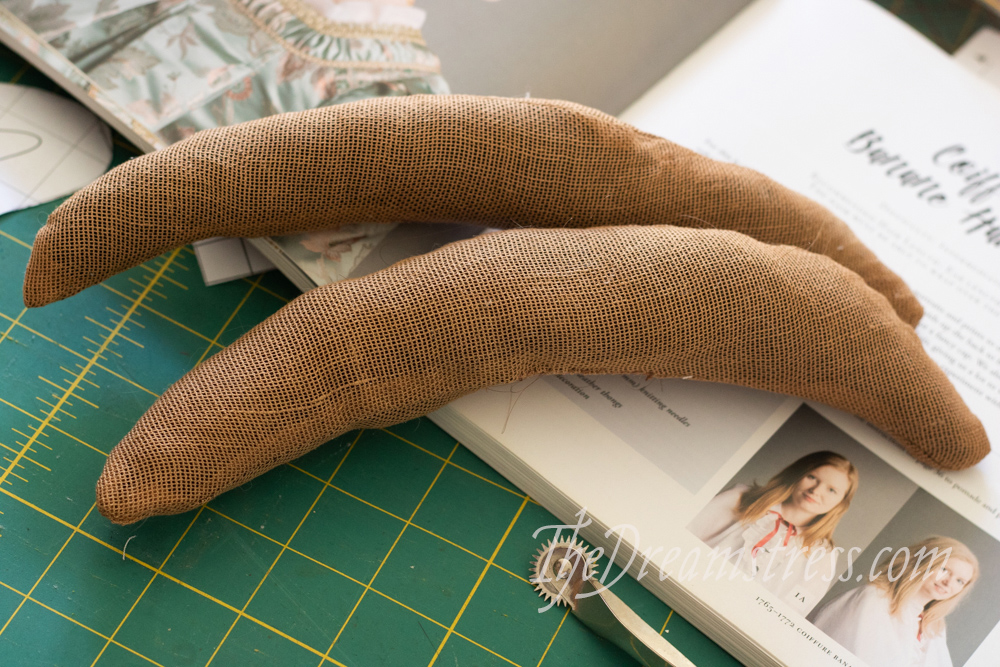

I’ve made the 1760s/early 70s ‘banana’ in two slightly different shapes/lengths:

And the early 1780s ‘grub’:

And the later 1780s ‘arrowhead’:

My Edwardian hairpieces are extremely simple. Tubes in different lengths, with rounded ends:

Fabrics:

I’ve tried three different fabrics: a true leno weave cotton gauze (lower left), slightly textured wool knit (upper) and fine merino knit (lower right in dark grape).

The leno weave is by far my favourite: it’s easy to pin into, and the texture helps it to grip to hair and stay in place. The textured knit also works well, although it’s slightly harder to pin into. The merino, while it looks closest to the fabric used in the AD book, has been the least successful. It’s very tricky to pin into, and slips all over the place.

I’m very happy with the leno as an Edwardian-appropriate ‘rat’ fabric, but am not sure if it’s right for the 18th century. I’m planning on experimenting with a woven wool fabric, and perhaps a linen, for future 18th century pads. Wovens rather than knits seem more plausible in the 18th c, and a woven wool would certainly be more durable than a knit with lots of use and pinning.

Stuffings:

This is where things get…interesting.

For half my hair cushions I’ve used wool roving:

And for the others, I’ve used my own hair.

Yep.

It’s absolutely historically accurate. Using your own hair to stuff rats is documented throughout the 19th and early 20th century, and was almost certainly done in the 18th century as well. Why wouldn’t women use it? It’s free, it happens naturally, and using your hair to make it look like you have more hair just makes sense.

I collect mine off my hairbrush every day, and when I have enough I wash it just like you would wash your hair: warm water, shampoo, a bit of friction, and then dry. It tangles and felts, but that’s fine for hairpieces.

I’d use it for all my hairpieces, but I often end up dressing other peoples hair, and it’s nice to have hairpads to lend them that aren’t actually my hair (though why sheep’s hair is fine, but your own is weird, doesn’t really make logical sense).

Wool rovings do have the advantage of being less likely to work their way through the covers. Hair hairpieces can end up being a little…hairy.

These three are all wool.

I also want to try granulated cork and horsehair stuffings. I used all I’d got for testing the Frances Rump, and am having trouble sourcing more with Covid and shipping delays.

The Pads in Action:

Both Jenni & Elisabeth got a little extra height with the ‘Arrowheads’ for the Amalia Jacket photoshoot.

As did I with my witchy chemise hairdo:

The American Duchess 18th Century Beauty book, and Kendra of Demode’s ’18th Century Hair and Wig Styling’ (which is due to be re-published very soon!!!) both have great tutorials for using pads and styling your hair. I’ve combine their techniques depending on time constraints and how historically accurate I want to be.

I just used one of the Edwardian rats to give my friend Emily’s fine, delicate hair some volume for an Edwardian photoshoot:

Natalie has a great tutorial on making and using Edwardian hairpieces on her blog: A Frolic Through Time. She uses a slightly different technique than I do to make her hairpieces, but both work beautifully.

And finally, I made the ones filled with hair first, and they were my entry for:

The HSM 2020 June Challenge ‘It’s Only Natural’

What the item is: three (banana, grub and arrowhead) 1780s hair-filled hair pads

How it fits the challenge: The cotton leno weave is dyed with natural dyes (tea) to match my hair colour, the wool knit is wool, and all three are filled with my hair (which is definitely unexpected in this day and age!)

Material: cotton leno weave, wool knit.

Pattern: the American Duchess 18th c Dressmaking book, and period sources.

Year: ca. 1770, 1780, 1785

Notions: cotton thread, hair.

How historically accurate is it? I’m not at all sure about the fabrics, and human hair as a pad filling isn’t fully documented in the 18th century (as far as I’m aware – mentions don’t make it clear if it’s horse or human hair), although it’s extremely likely.

Hours to complete: about 2 – most of it drawing out the patterns 🤣

First worn: October 31 (arrowhead pad).

Total cost: $1 or less – the fabric was all scraps.

But wait, there’s more! I even made carry bags for both sets of hair pads:

Hot pink for hair, and white for wool, naturally!

Some day I’ll have enough to need 18th c bags, and Edwardian bags. Guess I’ll need some 18th c themed fabric too!