We all know about Queen Victoria’s obsession with Scotland and her castle in Balmoral, and how this led to the name ‘Balmoral’ being applied to all sorts of fashion items. One of these was the balmoral petticoat.

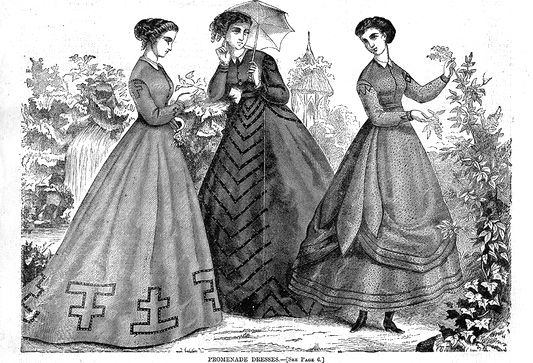

The balmoral petticoat was a coloured petticoat that was intended to show at the hem of a drawn-up skirt for walking and sportswear in the 1860s and 1870s.

The balmoral petticoat could be worn over a hoopskirt or crinoline or have hoops built into the petticoat, and (according to some sources) include a horsehair stiffener as part of the petticoat itself.

The most common Balmoral petticoat was red wool, often with 2-4 black stripes running around the hem. Later in the 1860s there are mentions of balmoral petticoats in plaid or striped wool, and even cotton balmoral petticoats in the Americas.

Rachel Bodley (1831-1888), the first female chemistry professor at Philadelphia’s Women’s Medical College from 1865 to 1873, in a balmoral petticoat. via here

The petticoat was said to originate at Balmoral, with writers in the 1890s claiming that during the 1860s royals at Balmoral wore high laced boots (Balmoral boots), scarlet petticoats, and their skirts drawn up to walking length for practicality, showing glimpses of the scarlet petticoats, the boots, and bright coloured stockings.

The balmoral petticoat was most popular at the height of the crinoline era, but quickly became a victim of its own popularity and practicality. Fashion has never loved sensible garments, and balmoral petticoats were eminently sensible: warm, durable, easy to walk and move in. They were adopted by all levels of society almost immediately (there are numerous mentions of slaves in the American South wearing balmoral petticoats in the 1860s), and quickly discarded by the upper levels of society. A variant of the Balmoral petticoat (sans hooping) remained popular with older women and the less fashionable for decades after the crinoline was discarded. As a result ‘red flannel petticoat’ became synonymous with provincial fashion and the elderly.

Margherita of Savoia-Genoa in the late 1860s carte de visite by Henri Le Lieure. Is this a balmoral petticoat? Debatable

Sources:

O’Hara, Georgina, The Encyclopedia of Fashion: From 1840 to the 1980s. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. 1986

Lewandowski, Elizabeth J, The Complete Costume Dictionary. Plymouth UK: Scarecrow Press. 2011

That’s so interesting. Something else I had never heard of and wouldn’t of recognised in a painting/photo ever. So that’s something else I have learnt from this fantastic site.

Thank you Karen! Do forward on a link if you recognise on in a painting or photo later.

I suppose that level of practicality was a little out of place in 19th century fashion. It’s a shame though; I think they look great.

They are quite sweet aren’t they?

We tend to remember the excess, but there were the occasional examples of very practical clothes in the 19th century.

There is a lovely story of Queen Victoria being very impresses with Princess Alexandra (when she was first considered as a potential bride) for wearing jackets with skirts – so that she could have a whole wardrobe with just a few items. And, of course, if you believe the later 19th century journalists, the whole Balmoral petticoat trend came out of royal practicality.

Oh, wonderful! Another excellent addition to the vocabulary!

What a sensible garment! Warm, sensible, and attractive, too. Nothing like a flash of plaid or a nice stripe or three. Red flannel was a fine thing – very popular in all sorts of clothing. Have you ever come across the military coat called a British Warm? I’ve met one, and you’d have had to have been eating your porridge regularly to walk in it – so heavy! So many good layers.

It is beautiful, isn’t it? Why not show off your skirts–like the Medieval surcoat outfit, and even the Tudor split skirt. But you know what I thought of? I thought of the early aught’s fashion for showing your bra. I mean, if you are going to make your underwear public, then make it pretty! And wearing a real bra rather than mussing with those strapless/convertible/racerback things is really ever so much more practical.

And yes, I did just compare Queen Victoria to Carrie Bradshaw–but hey–but just wanted to be practical and comfortable!

You’re right, Elise! This could have been the beginning of the move to let underwear become outer wear.

I remember giggling about twenty years ago when girls started buying 1950s/60s lace and nylon knee length slips/petticoats, and wearing them outside other garments as light tunics. Layering gone into reverse.

I may or may not have done that! Man, I hadn’t thought of that in years!

And that flash of red really would have been quite pretty!

Actually, if you think about it, Balmoral petticoats are kind of the last-gasp of interchangeable underwear/outerwear.

Remember that in the 18th century poorer women wore their stays as work clothes, and even among the rich petticoats could be worn as outermost wear, or under other petticoats. And then there is the ‘chemise a la reine’ – literally ‘the queens underwear’, where an undergarment became an outer dress.

It’s only in the 19th century that we see this huge distinction between under and outer wear (and even then, little girls would have their drawers peeking out from beneath their skirt) – and even then Amelia Bloomer advocated a costume where large portions of bloomers (albeit made out of outwear fabric) showed.

So Madonna? She was just behind the times 😉

I remember reading (though I forget where so sadly I can’t supply a source) that people thought red flannel protected against disease and that’s one of the reasons it was such a popular choice.

I’ve read that too, and can’t remember the source either. I’ll keep an eye out for it!

Don’t quote me on any of this but, I think it might have been a matter of heat. In the system of humors red was associated with blood and vitality, so it would make sense to use it for a sickly person.

Myself and another re-enatcor for the Washington Civil War Assn made ‘sporting costumes’ for a re-enactment in September. ‘Short hoops’ – we used wool tartan, taffeta tartan and flannel.

Oh cool! Are there images of you in them online?

Our photographer got sick – and like a couple of dolts we didn’t have a back up!! Vicki has a picture of her’s from the Veteran’s Day Parade in November – I’ll see what I can do!!

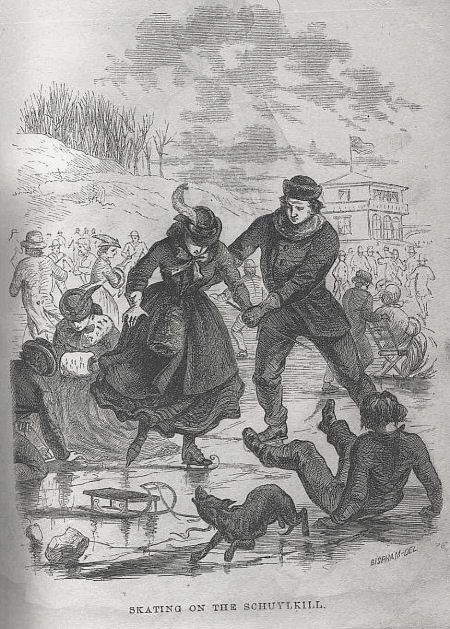

One of your historical illustrations is of a scene near where I live!

The Schuykill River, where the little skating scene is set, flows into the Delaware River at Philadelphia; this Wikipedia page tells more about it.

Interesting! I’ve never heard of a Balmoral petticoat, although I’ve seen pictures of what I now recognise as one.

Also, as a native Pennsylvanian, I’m curious whether you know how to pronounce Schuylkill – most people are astonished when they first hear it said. It’s a bit of a party trick ;-P

I have no idea what the proper way to say Schylkill is! It’s a bit of a ways from my neck of the woods 😉 I know how to say things like humuhumunukunukuapua’a and Ngunguru and Petone (it’s not Pet One). Please share!

I love humuhumunukunukuapua’a. I wonder if it’s pronounced as a Czech would pronounce it, or not…

And I love sensible garments that are also pretty. Therefore, I now love barmoral petticoats.

Dang it. I can’t find a single Youtube video where they say humuhumunukunukuapua’a, properly so that you can compare if it would be said the same in Czech!

Balmoral. Bar moral? 😀

There’s a town near where I live called Maugerville but it’s pronounced major-ville. A lot of the names around here are french or Aboriginal so there are a lot of odd spellings and pronunciations.

Thank you for the terminology post!

They are always so interesting because they are usually things I have never heard of.

Bellefontaine in Ohio = ‘belle-fountain’,

Russia in Ohio = ‘russie’

sigh…

Some more Balmoral skirts!!

victorianamagazine.comvictorianamagazine.comhttp://www.victorianamagazine.com/archives/13314

I have a question ‘red flannel’ what actually is it material wise? I’m guessing it’s not the same material you’d make a flannel you wash your face with from.

Are these the same red flannel petticoats mentioned in the railway children?

Well, flannel these days is the slightly fuzzy cotton or cotton blend fabric you are probably most familiar with from pyjama bottoms (face flannels are so called because they actually used to be made from this, rather than towelling). Flannelised fabric really means that the surface has been brushed to achieve a slightly raised, fluffy finish, which you can’t see the weave in. Flannel petticoats would be made of this – most probably in flannelised wool, for warmth, or in a wool blended with another fabric, or later in cotton flannel. I’m afraid I’m not familiar with the railway children.

Thanks for clarifying. They have something like that in the fabric shop. Although I suspect its synthetic rather than real cotton.

You should try to see the film of ‘The railway children’ with jenny augutter in (1970 I think?). Its got some lovely scenery and costumes. The book was published in 1906.