I’ve been doing a lot of experimenting with making linen buckram in the last year and a half, playing with using both historically accurate gum tragacanth, and a much cheaper and easier to source modern equivalent: xanthan gum.

We’re getting very close to launching Scroop Pattern’s and Virgil’s Fine Good’s first collaboration: a 1780s stays pattern with extensive historical instruction. Historical stays use linen buckram, so here’s what I’ve learned about it to help you make your own.

What is linen buckram?

Linen buckram is stiffened linen. It was used in 17th, 18th and early 19th century sewing as support layers where stiffening was needed, such as in stays, stiff collars, stomachers, and hatmaking.

It’s made by coating linen with a gum paste, usually gum tragacanth, or xanthan gum, and then letting the gum dry. The more layers of gum that are applied, the stiffer the linen gets.

Here is what it looks and sounds like in motion:

In addition to historical sewing, I think it has lots of potential for general costuming: particularly for costumers like me, who are away from main centres and can’t always get the usual materials.

How to make linen buckram:

Choose your linen. You can use pre-cut pattern pieces for whatever you need the linen buckram for, or whole pieces of linen, which you cut later.

Linen buckram works best when it’s made from a mid-heavyweight linen. I’ve had the best results using coarser linen: the gums stick well to the more textured weave.

Place your linen on a surface that won’t be damaged by moisture, or transfer colour when it’s wet.

I use laminated posters that an old workplace was throwing out: the gummed linen doesn’t stick to them, they are smooth, and they are larger and lighter than a plastic cutting board. Large plastic bags would also work. Cardboard can work, but sometimes stains white linen. I also use my tiled fireplace surround.

Use a brush (preferably a natural fibre one) to brush the gum (xanthan or tragacanth – see below on how to mix them) on to one side of your linen. When one side is fully coated, flip the linen pieces over and coat the other.

Let your linen dry (I leave it outside in summer, and in front of the heater in winter).

When your buckram is dry check the stiffness: if you want it to be stiffer you can add another layer of gum.

If your cat is willing to lie on it that’s probably a good sign it’s dry…

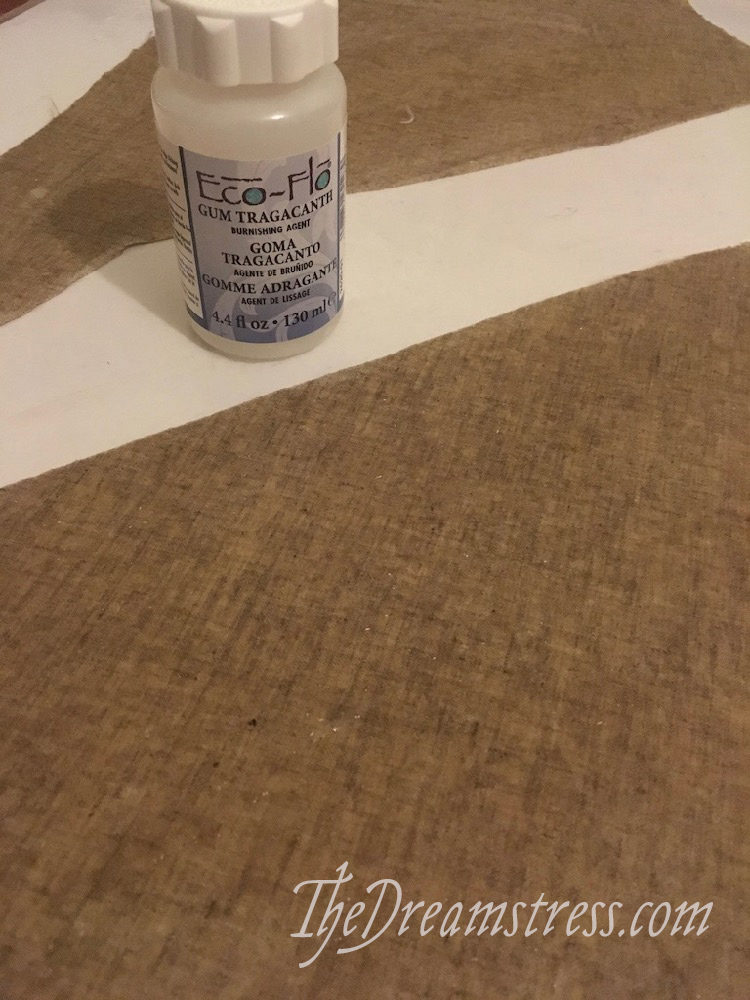

Gum Tragacanth

Gum tragacanth is the most easily obtainable historically accurate gum for making linen buckram (less easily obtainable historical alternatives are glues based on animal hooves).

Tragacanth is mainly used today by bakers and pastry chefs, and in leatherworking. It can be bought pre-mixed as a liquid, or in a dried, flaked form. Googling (or for bonus awesome-person points: Ecosia-ing) ‘buy gum tragacanth’, should help you to find a source for it in your area.

I only been able to source pre-mixed gum tragacanth in NZ, so so far my experimentation has all been done with this variety.

How to use it:

Easy-peasy. Pour your gum tragacanth into a bowl. If you want you can microwave it slightly to warm it, or add a tiny, tiny bit of hot water, both of which will make it more viscous.

It’s best to work outside or in a well ventilate area.

Pros & Cons of Gum Tragacanth:

Pros:

- It’s historically accurate.

- You’ll know that the result you achieve is accurate, and will last over time just as it would have in the 18th century.

- Really easy to use if purchased in the liquid form.

Cons:

- It’s harder to find: it’s a specialty product, and very few stores have it on hand. You’ll probably have to special order it.

- It’s expensive. In NZ a little bottle barely big enough to make linen buckram for 1 pair of stays is almost $25.

- It stinks. Not horribly, but it definitely has an odour.

- Some products marketed as ‘gum tragacanth’ are just xanthan gum, so you really have to be careful about what you buy if you want to be sure it’s tragacanth.

Xanthan Gum

Xanthan gum is definitely not historical: it was discovered in the early 1960s by USDA chemist Allene Jeanes (woot woot – women scientists ftw! Click through to admire adorable informal photo of her and JFK). It’s a byproduct of corn and fermentation, and is named after the bacteria used in the fermentation process that creates it: Xanthomonas campestris.

Xanthomonas campestris is better known as ‘black rot’ for the effect it has on broccoli and other brassicas. When I was a teen my parents permaculture farm had a black rot infestation, and it was very stressful.

Slightly icky source aside, xanthan gum is ubiquitous in modern cooking. It’s used as a thickener in all sorts of food, and is widely available in powdered form at supermarkets.

How to use it:

Mix 1/2 a teaspoon of xanthan gum powder with 1 cup of hot water.

Stir like mad:

Don’t worry if there are a few lumps and un-mixed looking spots. They will go away as it thickens, and any remaining ones won’t be an issue when you work with it anyway.

Leave it to sit for 5 minutes. It will thicken up beautifully.

Once it’s thickened to approximately the consistency of kids glue (or my video of gum tragacanth pouring) it’s ready to be used.

If you use too much xanthan gum powder, you’ll end up with a horrible gloopy, impossible to work with mess:

That was 2T in 1/2 a cup water: not a good idea!

Pros and Cons of Xanthan Gum

Pros:

- Very affordable. My bag of 100g of xanthan gum cost about $10, and will easily make enough buckram for 20 pairs of stays.

- Much easier to source.

- Not stinky

Cons:

- Not historically accurate

- It may not last and act in exactly the same way gum tragacanth would.

- Slightly messier to work with, because you have to mix it up.

So how do the two compare?

I’ve made and worn (reasonably extensively) one pair of stays with gum tragacanth linen buckram, and one with xanthan gum linen buckram, and honestly, I couldn’t tell the difference when sewing or wearing them.

The only thing that was slightly different about the two is that the xanthan gum dries in slightly shiny, smooth patches where its in contact with a really smooth plastic surface. And this may be just because I don’t mix it perfectly smooth.

In terms of viscosity, how they feel when painting them on, length of time to dry and how they dry, how the finished product feels, and how it feels to work with the finished buckram, they are virtually identical.

So far the two buckrams have held up equally well over time. If I notice any change with more wear I’ll update this post.

As a historical sewer who uses historically accurate methods to test an experience them, but it’s always concerned that all my costumes are perfectly accurate, I would definitely consider xanthan gum to be a viable alternative to gum tragacanth when making linen buckram.

I’ve finally found a New Zealand source for dry flaked gum tragacanth, so I’ll be trying that the next time I need linen buckram, to really compare the two gums, and continue my experimentation. Other than that I will probably use xanthan gum for my linen buckram making from here on out – or at least until I finish the bag I have, which may take a while!

Further information:

- Burnley & Trowbridge have an excellent youtube tutorial on how to make your own

- The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Dressmaking discusses making linen buckram

Lovely post, as always.

I’m currently working on a research project concerning Colonial clothing in 18th century Brazil and sewing a pair o of stays is a possibility. So, I have two questions:

* Would you point me at some primary sources of buckhram use in 18th century staymaking?

* When is the pattern going to be available?

Thank you!

* Patterns of Fashion 5 discusses buckram and has some good starting points for primary sources that mention it.

* We’re working on it as fast as we can, but both have to fit it around other life things, and we’ve both had big things come up (Amber is pregnant!).

Fascinating! Having celiac, I’m well familiar with xanthan gum. Is tragacanth also edible? Or is it only only only used in sewing?

Tragacanth is edible, and is/was used to make paste decorations, the binder in hand-made pills, and as a binder for artist’s pastels, incense and cigars.

Very neat. Thanks for answering!

tragacanth was also used for making hair preparations, eg “bandoline”. Unclear whether this was as a men’s pomade or more like a setting gel for curls. But in one of my 1980s home made cosmetics books there’s a recipe where the author used it as a comb in, brush out when dry hair conditioner. She loved the results, as it made her thin hair look much thicker. I got some tragacanth myself (from a chemist back then) and made up the recipe, quite liked the effect on my hair, I have thick hair anyway, but it was nice as a conditioner. The tragacanth was very difficult to dissolve, and also eventually the preparation went mouldy before I could use it all up over several months (despite the use of benzoin tincture as a preservative).

Oh I know that book! It was in the library and I just kept continuously borrowing it when I was a teenager, till I’d pretty much memorised it. Hence knowing exactly which book from your reference 😉

I could never source gum tragacanth, and I have very curly hair. I always wondered what it would do to my hair. It sounded divine for her hair.

Thank you for your clear and thoughtful information. You are a treasure.

Thank you! <3

Oh that’s fascinating! I appreciate your comparison of both gums. With regard to hatmaking, does the use of something water-soluble as stiffener mean that hats would go limp in the rain and then be difficult to fix? When I read, in a novel, about a lady “remaking” her hat, do you know if that would that have involved refreshing the structure of the hat with more gum?

And thanks for the push to actually put Ecosia as my default! It sounds like their privacy settings may also be better than the big G.

You’re welcome! I suspect that buckram made this was would go limp, but want to do some experimenting with it and hatmaking. To the best of my knowledge remaking a hat was about re-trimming, or re-covering a solid structure with fabric, not about re-gumming. It’s certainly about re-trimming in mid 19th c books.

What about gum Arabic? Do you know if it would work in a similar way?

I do not, but I suspect most gums would probably act fairly similarly. You could probably even use standard modern glue if you didn’t want them to be water soluble.

May I ask if you have historical instructions for the use of animal glue? (Since I do have ready access to that….) Many thanks for the extremely useful post!

I do not I’m afraid. It’s something I’ve never looked into because I don’t have access to it.

Hm. It’s easy to source from historical art supply shops in Northern Europe; I’d offer to post you some, but I quite understand that the emissions of shipping round the globe would not be acceptable to you. However, I did locate some varieties in gilding and woodworking supply stores in Australia – the rabbit skin glues appear to be imported from Europe, but the hide glue is not specified. I do not have any experience with these particular suppliers myself, of course, but I can send you the links, if that would be of interest or use to you – and if shipping from Australia would be acceptable.

PS. In fact I also located a gilding supplier in New Zealand; however, they say their hide glue is from Germany, and don’t specify the origin of their rabbit skin glue! And I’m not sure which would be needed for making buckram…

Whilst I’m not sure if it could be classified as “buckram” per se, the soles of Chinese cloth shoes are made out of a scrap “buckram”. Scraps of fabric are adhered to a clean, smooth surface (a new cutting board, for example- in the Chinese countryside people took a door off its hinges and used that) with flour paste. This assemblage is then taken out into the sun (it’s usually made in summer) and allowed to dry. Once dry, the soles of the shoe to be made are cut out from the buckram. Two to four sole layers per shoe seems to be the convention.

How interesting. Sounds very similar! Thank you so much for sharing.

Quite fascinating, thank you! And glad it’s cat approved! She’s gorgeous.

Ooo! Now I’m tempted to try constructing my own hats (I doubt my sewing skills are up to stays yet). But perhaps I’d better stick to Finishing The Projects I’ve Already Started for a while!

How very interesting I learn so many things from you. Do you know if either of these gums can be used to stiffen felt?

If you visit the US, have friends/family visiting you, and for US readers (possibly all of N. America), Weaver Leather sells gum tragacanth – $20 for a quart, $44 for a gallon.

Happy Weaver customer, NAYY.

https://products.weaverleathersupply.com/search?w=gum%20tragacanth

book binders and hat makers use buckram, you can find it on those sites, but it isn’t cheap.