My ‘Smooth Sewing‘ trousers for the HSF ‘Innovations‘ challenge were made of rayon (as is the 1940s aloha shirt I paired them with), so it seems high time that I do a terminology post on rayon and the other ‘semi-synthetic’ or ‘manufactured natural’ fibres.

Rayon is the generic name for a whole family of fabrics made by dissolving cellulose fibres in chemicals and extruding the resulting viscous solution. Different chemicals and variations in the processes yield different types of fabrics in the rayon family. Viscose (called rayon in the US), cuprammonium (also known as cupra, cupro and Bemberg silk or Bemberg rayon), nitro silk, acetate, modal and lyocell are all types of rayon, as is most ‘bamboo’ fabric – which is simply rayon made from bamboo rather than other cellulose bases. Art silk (or artificial silk), is an older term for rayon, as is mother-in-law silk (which gives an indication about how people felt about rayon when it was first invented).

The first manufactured natural fibres have their origins in the exciting experimentation that characterised the birth of modern chemistry in the mid-19th century (a movement that also resulted in the first synthetic dyes).

Scientists discovered that cellulose could be dissolved in various solvents such as acetone and ether, and almost immediately hit upon the idea of creating a silk-like filament fibres from the resulting liquid. In the mid 1850s an otherwise little-known chemist named Georges Audemars created the first artificial silk fibres by dipping needles in cellulose dissolved in a solvent, and drawing the needles out to form a thin fibre. His method was obviously impractical for mass production. It took another half a century of tinkering to create a commercially viable manufactured cellulose based fabric.

His method, known as nitrocellulose, did go into production in the 1890s after further developments by Comte Hilaire de Chardonnet (mentioned in NZ papers in 1888) based on filament development for lightbulbs. Unfortunately the fabric was extremely flammable, had aesthetic issues, and was more expensive to produce than the other two competitors that had since arisen: acetate and cuprammonium. Despite these drawbacks, and despite being popularly dubbed ‘mother-in-law silk‘, nitrocellulose was manufactured throughout the first decade of the 20th century, until the disruptions of WWI ended its production.

By the early 1900s manufactured cellulose fabrics of various varieties were making headlines around the world. Articles raving about it had appeared as early as 1894, and by 1906 they reached a fever pitch with headlines like “The Wonder of Cellulose” and declared “Death of the Silkworm” and “Artificial Silk Can Be Made Cheaper Than Rags.” Viscose was sold in the UK from 1905, in the US from 1910, and in New Zealand from at least 1911.

World War I delayed the development of rayon and other cellulose based fabrics. When the war ended in 1918, society embraced new technology of all varieties as hallmarks of a new world which had been washed clean by the horrors of war, and could start fresh. Processed cellulose fabrics was one of these new technologies, and its popularity rose throughout the early 1920s.

Viscose in particular was originally marketed as a silk alternative – or artificial silk, shortened to art silk, to further veil its origins. Proponents raved that it was “so soft and glossy that it will deceive even experts when woven.” Less enthusiastic observers sneered that it was simply “disguised cotton” and noted “artificial the article certainly is, but silk it is not – any more than celluloid is marble.”

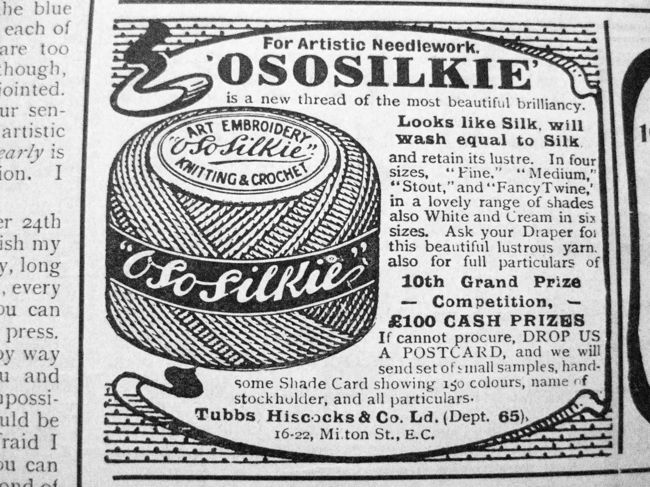

Despite the detractors, by 1925 rayon, with its ability to mimic both cotton and silk, combined with a significantly cheaper price tag, especially compared to silk, was being manufactured in large quantities in the UK, Germany and the US, and to smaller extents in Italy, Japan and other countries. Production of rayon in the UK almost quadrupled from 1924 to 1926. Silk remained pre-eminent for those who could afford it, but art silk was an attractive alternative to those on a budget. Art silk was manufactured as yarns for embroidery and knitting, as a flat fabric, as a crepe fabric, and as a velvet, among other types of fabric.

Rayon was also mixed with wool and cotton to create blends that were often cheaper than either of those fabrics in their pure form, or simply to create new and exciting fashion blends.

Sports dress that will be much in evidence this winter. The material is Cobra, one of the new rayon and cotton fabrics that will be made up into sports frocks as well as gowns for tea dansants and afternoon wear. Auckland Star, 11 April 1928

The popularity of art silk prompted chemists to try to devise a fibre that could mimic wool, resulting in the development of the short-lived and unfortunately named Sniafil. The fibres properties were apparently no more impressive than its name, and it is not mentioned again after 1927.

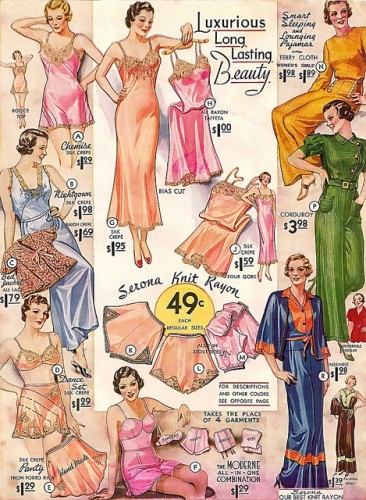

The entire manufactured cellulose fabrics industry became increasingly important with the economic crashes in 1929: more and more people could not afford real silk, and turned to art silk as a cheaper alternative. The first fashion illustrations for rayon frocks appear in NZ papers in 1927 (and these illustrations would have come from overseas, so reflect a clear global trend).

1930s rayon crepe Japanese import robe with rayon embroidery

The drawback to rayon was its quality: it crumpled more than natural fibres, and often did not last as well. Still, 1931 home economics textbooks advised that “with proper care and laundering, rayon may give as satisfactory wear as silk”. Early rayons were so weakened by water that even slight rubbing when washing could produce holes in the fabric. This weakness in water made rayon unsuitable for military use (can you just imagine how bad a parachute that weakened when wet would be?), so rayon filled the gap for a fashion fabric left by silk (which was in high demand for parachutes, and in short supply due to trade interruptions) during World War II.

In addition to an increase in demand for rayon, World War II also saw huge improvements in the qualities of rayon. Early rayons were (as mentioned) weak in water, couldn’t take hot ironing, and prone to creasing in wrinkling. Research into rayon technology spurred by a need for better, cheaper, fabrics during the war helped to improve the fabric, and also produced nylon, the first fully synthetic fabric.

Rayon has been continually improved since the end of WWII, based on fashion trends and cost demands. It’s now softer, stronger, more breathable, and easier to launder and care for. It’s also going through a bit of a resurgence as a fabric, motivated in part by rising costs in cotton caused by serious droughts in major cotton producing areas. Rayon, in all its forms, is easily found in off-the-rack garments and fabric stores – at least for now.

I’ve used art silk, rayon and viscose as synonyms up to this point, which is how they were used historically, but they aren’t quite synonyms today. So what is the difference between rayon and viscose?

Viscose was the trade name for the specific process developed by Charles Frederick Cross in 1894. It was used as the generic name for fabrics produced using variants of that process until 1924, when the holders of Cross’s patent petitioned in the US to have the name restricted to their process, and the actual viscous liquid, which could also be used to make cellophane. From 1924 viscose and other cellulose fabrics produced with similar processes were called by the generic name rayon, or art silk in the US, though they continued to be called viscose in Europe. Thus, modern equivalents of the fabric are called rayon in the US, and viscose in NZ/Australia/the UK today.

A smart three-piece sports ensemble of wool and rayon weave, featuring the popular jacket and set off by a large silk bandanna. Auckland Star, 25 June 1928

There was a time though, when the fabric was called rayon in New Zealand Advertisements for rayon, rather than viscose or art silk, first appear in New Zealand papers in March 1925. In the later half of the 1920s, and throughout the 1930s & 40s rayon was the most common term for manufactured cellulose fabric in New Zealand fashion articles and advertising. Only when rayon fell out of favour (replaced by the new fully synthetic fibres, like nylon) in the post war period did the name disappear. When rayon/viscose experienced a resurgence in the 1980s and new millennium, it was brought back to New Zealand under the name viscose.

Today rayon is the generic term for all of the manufactured naturals, while viscose implies a specific process and materials – so viscose is a rayon, but not all rayons are viscose. There are also:

– Acetate, acetate rayon, or cellulose is the second oldest manufactured cellulose fibre, with origins dating back to 1865, though it wasn’t until the turn of the century that a process that was commercially satisfactory was developed (interestingly enough, by the Dreyfuss brothers, who were also responsible for the first synthetic indigo dye). Acetate differs from viscose significantly in that in that acetate is hydrophobic (reacts very poorly to water and must be dry cleaned) and viscose is hydrophylic (loves water and absorbs lots of it). Acetate did poorly at first as a fashion fibre because the initial process was hard to dye (as it couldn’t be put in a dye bath) so was used primarily for industry. Acetate also reacts poorly to heat and melts easily – this does mean that it is one of the few semi-natural fibres that can be permanently pressed into pleats. Because of these drawbacks it wasn’t manufactured commercially on any great scale until at least 1924. Variants of acetate are Triacetate and Diacetate.

– Bamboo rayons (from bamboo fibres) – simply viscose or other manufactured naturals made with bamboo as their cellulose base. Bamboo can be processes into a fibre in two ways: mechanically, or using chemicals (as a rayon). The mechanical process is expensive and time and labour intensive, and results in a much stiffer, less attractive fabric. The rayon process produces a much nicer fibre, but is not particularly environmentally friendly. In some countries, such as the US, bamboo rayons must be marketed as such unless they are entirely mechanically processed. There are no such rules in New Zealand. It is possible to buy mechanically processed bamboo (it’s rather like a stiff, coarse linen), but its usually blended with other fibres to make it softer and more wearable. I’m reasonably certain that the stripes in my Subtly Striped petticoat are manufactured bamboo.

-Cuprammonium rayon is simply cellulose dissolved in a cuprammonium solution. Sold as cuprammonium, cupra, cupro, bemberg and bemberg silk, after the J.P. Bemberg company, who improved it and first produced in commercially in 1901. Cupro is usually a very light, fine, soft fabric, and is used as linings in quality suits and dresses, as it tends to last better than silk, but is nicer to feel and wear than acetate. It is apparently illegal to manufacture in the US at the present, due to the chemicals used to make it.

-I’ve been told by more than one American seamstress of my grandmothers generation that in the post WWII attempt to rebuild Japan’s economy fancy brocaded rayons were sold as ‘Kyoto silk‘. I’ve never found any marketing or research which definitively substantiates this, and Kyoto has always been famous for its gorgeous fabrics of real silk, so rebranding rayon as ‘Kyoto silk’ seems particularly unscrupulous on the part of marketers.

– Lyocell, trade named Tencel, is a relatively new rayon, only invented in the 1980s. Unlike most rayons it is strong when wet, and is highly absorbent. It can also be made to mimic a variety of other fibres and finishes, from suede to silk. It can be quite hard to dye, and has a tendency to pill, though both of these drawbacks can be overcome by additional processing. Lyocell is often marketed as the most environmentally friendly of the rayon processes, though some manufacturers use harsher chemicals to make the process faster and cheaper, as it is also the most expensive of the rayons to produce.

– Modal, is most similar to lyocell, and like lyocell is extremely soft and very absorbent. Along with lyocell it is currently being heavily marketed as a ‘green’ fabric.

Sources:

Cant, Jennifer and Fritz, Anne, Consumer Textiles. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. 1988

Garfield, Simon. Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour that Changed the World. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 2000

Joyce A. Smith. Rayon — The Multi-Faceted Fiber. Ohio State University Rayon Fact Sheet

Rathbone, Lucy & Tarpley, Elizabeth, Fabrics and Dress. San Francisco: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1931