When you find an old book with a title like ‘My Official Wife‘ for 50 cents at an op shop, how could you possibly pass it up? Even if it’s terribly battered and slightly falling apart? With that name, you just have to know what’s inside!

Little did I realise when I bought it that My Official Wife was once well known. It was a bestseller when it was published in 1891, and made Savage a household name.

It’s also hilariously, awesomely, terrible.

My Official Wife was Richard Henry Savage’s first novel, and it draws heavily on his life. Like Savage, the ‘hero’ (more on those quote marks later), Colonel Arthur Lenox, is a retired army man. Both men had experience serving in forces all over the world, from their native US, to Egypt. Savage & Lenox both had a single child, a daughter, who married a Russian noble & government official.

Colonel Lenox’s first visit to Russia to see his now-married daughter, and meet his extended family of highly-placed in-laws, precipitates the book’s action. Mrs Lenox elects to remain in Paris, so Colonel Lenox travels alone on the passport that lists both himself, and his wife. At the border an enchanting young lady who claims to be American (Miss Vanderbilt-Astor no less!), and to have misplaced her passport, convinces him to let her cross the border on his, as Mrs Lenox. This subsequently turns out to be a huge problem for the Colonel, because passport fraud in Savage’s Russia is a quick ticket to Siberia.

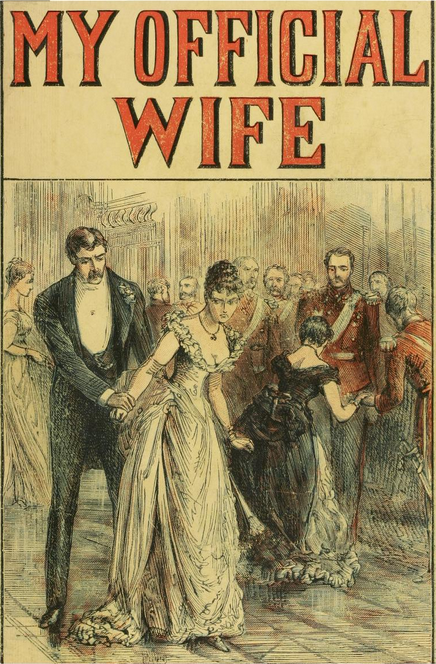

The Colonel doesn’t worry about this at first, because he’s too busy being dazzled by his superlative new bride. The new Mrs Lenox has, as an arsenal, every feminine wile the author could think of, actual brains, and the most spectacularly envy-inducing wardrobe of early 1890s couture. Her trunks literally spill Pingat & Worth garments, from tea gowns to ball gowns. The garments are described in rather nice detail, making for fun mental images for the historically costume inclined.

I could well imagine her ball dress, for the pivotal ball, looking much like this one (with the addition of a large and important pocket):

Evening Dress, House of Worth (French, 1858—1956), ca. 1890, 2009.300.635, Met

Lenox is easily taken in by the tea gowns and beguiling smiles. He soon finds himself entirely out-maneuvred on every front by his newly acquired spouse, who has her own reasons for wanting to remain Mrs Lenox – at least officially. Once he finally realises that the incredibly obvious is true, everything his new ‘wife’ has told him is a lie (she’s wasn’t even Miss Vanderbilt-Astor, gasp!), it’s too late.

As I read the book I tried to convince myself that Colonel Lenox must have been a satire of himself written by a clever and self-aware Savage. Surely no-one would write a story where the hero is so clearly an author surrogate, and also so clearly pompous, vain, terribly chauvanistic (even by the standards of the late Victorian era) and hopelessly dumb, unless they intended it to be tongue-in-cheek?

The further I read, the more I realised, with mounting horror, that Savage the author clearly thought that Lenox-the-author-stand-in was smart and brave and quick witted. In short, a hero the reader would identify with, admire, and cheer for. When he wrote “I might have been surprised at her sudden change in manner had I not been accustomed to the peculiar freaks and emotions of womanhood, having made the fair sex my study – perhaps, I may say, my plaything”, he meant it, despite also having written a character who was easily deceived, even in the face of multiple obvious clues to the contrary, by a pretty face.

Savage’s hero could only be as clever as his author (and the plot holes suggest that Savage really wasn’t that clever), but he could have at least written a hero with an admirable character – and Lenox is not. Lenox, upon finding that he’s brought a cuckoo into the diamond-lined nest of the Russian nobility, decides that if she’s going to pretend to be his wife, he’s going to take his full rights as husband (to use a really awful euphemism). Not-Miss-V-A only manages to fight him off by saying that if he is a ‘man’ he won’t take advantage of a defenceless woman, and if he’s a coward he will. He retreats, frustrated and angry, refusing to be a coward (because apparently that’s worse than a rapist?). The part where he would have been cheating on his very-alive real wife doesn’t even cross his mind – thought what the real Mrs Lenox would think, knowing that she’s being represented by an imposter, is mentioned with much hand-wringing every time his Official Wife presents herself as ‘Mrs Lenox’.

Though My Official Wife was reasonably well reviewed in it’s own time, critics did note that it was improbable, and the writing more verbose than polished. Savage’s numerous subsequent books were almost universally savaged. His heroes and spy systems were “incredibly idiotic and futile“, and his writing so notoriously sensationalist that reviewers mocked it at length (this one is particularly funny)

Despite the florid writing, unpalatable hero, and the tone-deaf author, the book is a fascinating look at Russian politics during the last two decades of the 19th century. It provides an interesting (if probably sensationalised) depiction of how reactionary and restrictive Russia was under the extremely conservative Alexander III. The Tzar spent most of his reign attempting to reverse all of the liberal reforms of his father, who had been assasinated. The plot revolves around lasting effects of Nihilism and the White Terror and the longer-term repercussions of Russian subjugation of Jews and reprisals in Poland & Lithuania in response to the January Uprising. Savage’s writing hardly does the heftier topics justice, nor are his sympathies and moralities likely to appeal to modern audiences, but as a glimpse into how the topics were presented in a pop-culture format in the Victorian era, it’s worth a read.

And the clothes descriptions are amazing!

Emile Pingat, mantle, 1891, Metropolitan Museum of Art 2009.300.337

Oh, thank you, thank you, for your detailed review of this “hilariously, awesomely, terrible” book. This was so enjoyable to read.

Lawks. What a horror!

I do like to see a novel where proper attention is paid to clothing, mind you. Patricia Wentworth’s novels are quite good in that respect, although from a later era. Not just describing what people are wearing, but giving the reader clues as to their character, state of mind etc. Skirt hem falling? Either they’re oblivious to the world around them, or they’ve given up on life. Perfectly clad for all occasions? Efficient – not necessarily nice, but efficient. No handkerchief? Habitually disorganized. I feel someone needs to write a monograph on the significance of the handkerchief in literature…

His ‘plaything’? Ugh! I used to love reading sensational Victorian melodramas as a teenger (The Heiress of Glengower is an especially juicy one!) and I love your review, though it does sound like an awful book! Great post!

Yeah, pretty ick! I thought the book was well worth a read as an insight into how topics like Russian repression of minorities was presented to the rest of the world. Apparently it was banned in Russia. I do wonder how it’s publication impacted his daughter and her husband, and Savage’s ability to visit them?

His wife was visiting her daughter and son-in-law in 1903 so apparently not a long-term effect.

I wonder if it was banned because of the bomb-throwing anarchist heroine and her ability to breeze past the Czar’s security.

Cringe-worthy! And in the so bad it’s amusing category.

It’s an interesting view of the values he assumes his readers will share with him.

Agreed on all three counts.

Interestingly, I couldn’t help thinking what a perfect movie it would make. It has been a film three times – once each in the 10s, 20s, and 30s, but it has all the elements you’re seeing in so many modern movies. Grittiness, decadence, moral ambiguity. Of course, if it were a modern film the male lead would start out blindly oblivious (as he stays throughout the book) and would have his blinders taken on, come to sympathise with the ‘wifes’ cause as he falls in love with her. And the part where he foils her plot would be this huge moral dilemma: does he risk her, or his daughter?

And modern directors would love that they could cast a very young woman against a middle aged man while being true to the story (*eyeroll*).

Is anyone else wondering what happened to Savage’s daughter and son-in-law during the Russian revolution? Eek.